Readers of the Design@Open blog probably know that blog rotas are planned months in advance. I had originally planned to use this this blog entry to think about the Smart City Robotics Festival in Milton Keynes, and particularly the Smart City and Robotics Symposium of 23rd September. Just as I was considering how to present what I learned from the Symposium for purposes of this blog, I learned about the RoboPASS scheme , with nearly £800,000 awarded to Milton Keynes City Council to explore the considerations local authorities need to take to facilitate the safe integration of multi-purpose robots into everyday public life. With this in mind, this blog post will undertake something of a conceptual zig-zag, reflecting about the RoboPASS in light of themes anticipated by the Symposium.

Readers of the Design@Open blog probably know that blog rotas are planned months in advance. I had originally planned to use this this blog entry to think about the Smart City Robotics Festival in Milton Keynes, and particularly the Smart City and Robotics Symposium of 23rd September. Just as I was considering how to present what I learned from the Symposium for purposes of this blog, I learned about the RoboPASS scheme , with nearly £800,000 awarded to Milton Keynes City Council to explore the considerations local authorities need to take to facilitate the safe integration of multi-purpose robots into everyday public life. With this in mind, this blog post will undertake something of a conceptual zig-zag, reflecting about the RoboPASS in light of themes anticipated by the Symposium.

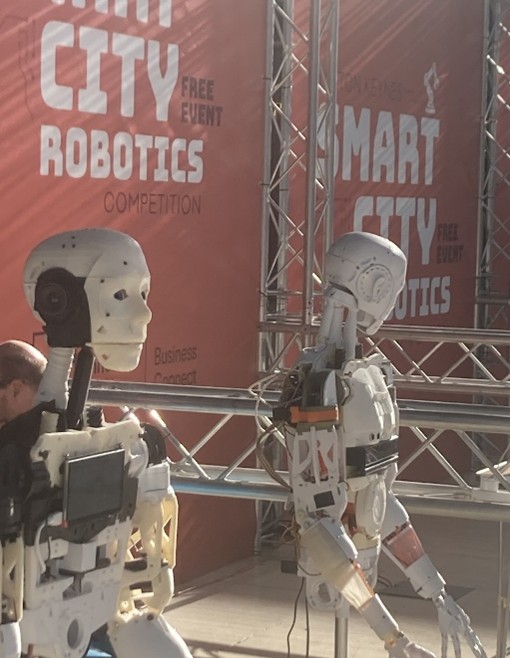

The Smart City and Robotics Symposium, part of MK Tech Week, took place in a large event area in a shopping centre (Centre MK). I found this interesting because the setting of the symposium brought a “smart city atmosphere” to a very public and busy commercial venue, so the event reached a diverse audience which included people with a clear technological background as well as families and children. The festival included robotic competitions where robots could be seen completing everyday tasks of various levels of complexity, as well as a symposium which provided a venue for public debate about the future of robots in smart cities.

Representatives of Milton Keynes City Council, research funding bodies, technology companies, and Smart City Consultancy ( which is now one of the partners of the RoboPASS programme) addressed questions centred on the future of smart cities and robotics, with answers often drawing attention to current developments in MK and discussing their implications for national strategies for robots and AI in cities. This entry will not provide an exhaustive account of the debate, but some of the points that caught my attention now seem even more relevant in light of the renewed interest and support in the inclusion of multi-purpose robots in everyday life as revealed by priorities in government funding.

Sophie Lloyd, head of economic development at MKCC, declared Starship delivery robots to be some of the most cherished residents of MK, emphasising their benefits in supporting inclusion during the pandemic, as well as their environmental benefits in terms of decreased car use. The role of MKCC in overcoming the challenges of robot adoption was defined as one of enabling innovation in a test bed environment, acting as an enabler in conditions of regulatory uncertainty, benefiting from the lucky position of having a public that expects innovation to happen. Other panellists also acknowledged the position of MK as a preferred smart city on account of the mentality of the public The design and urban form of the city were acknowledged as enablers for Urban AI, including robots as well as driverless vehicles.

Although the panellist were generally optimistic about the future of Urban AI in MK and, more generally, across the UK, they were also concerned about our collective capability to capture the benefits of innovation by creating translational pathways. The panellists generally agreed that UK can innovate and create IP, but often fails to scale up, exploit and translate, mainly on account of risk aversion. Urban robotics in particular was identified as a risky, expensive application as there are risks of hardware, of software and of regulation and all of them can cause a project to fail.

And here is where we fast-forward to the announcement about the RoboPass scheme a few weeks after the symposium. The scheme is funded by the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) as part of the Regulators Pioneer Fund designed to address real world challenges or opportunities to support innovation, with attention to creating a regulatory environment to better support innovation and working with local authorities to improve the delivery of regulatory functions. In the case of MK, the funding will help the city council explore the considerations local authorities need to take before allowing robotics operations. The city already has a leading deployment of delivery robots and is testing a driverless shuttle, with the scheme adding street cleaning, inspection of infrastructure and support for environmental services to the tasks autonomously performed by robots in the city. Importantly, by working with the National Committee on Robotics Regulations and Standards the scheme is expected to contribute to the creation of a scalable model that can be rolled out across the UK. The city council also hopes to launch a Smart City Testbed prospectus at the end of the project, explaining how other robotics companies can launch trials and services in the city.

Thus, we come back to the value of the city as a testbed in the age of AI. Much of the talk about AI at the time of this writing is centred on GenAI and in forms of machine intelligence that rely on massive data centres where large language models are trained by reading pretty much every single bit of text available online. This is only a specific, narrow slice of what AI can be, and one that despite all its potential is also inevitably associated to various problems. When I think about GenAI in comparison to the forms of AI that would be used to support urban robots, one major issue with GenAI is that it relies in the kind of gargantuan data centre that I probably would not want to see in my city. A second issue is that Large Language Models trained on internet data are simply running out of new things to read. They have reached the point where they have read pretty much everything that has been written, and it is difficult for machines to learn and improve when they do not have access to new data… And that brings us back to cities. Machine intelligences are enormously data hungry, and cities (smart or otherwise) are endless sources of data. Also, importantly, deployments of urban robots such as those used by Starship demonstrate that one does not need super-human intelligences and massive data centres to have robots performing useful tasks and delivering useful services in an urban setting. Much of the debate about GenAI seems to be based on the assumption that such intelligences will soon match and exceed those of humans ( a PhD level intellect in your pocket!, or so they say). However, many mundane, repetitive or risky tasks that need to be done in cities could be done perfectly well with a level of intelligence comparable to that of, say, a reasonably clever dog. Put together, those points build up towards a conclusion that a city with some talent, some appetite for innovation and some willingness to learn to live with robots may well be in a position to effectively find translational pathways to create and capture value from AI in new ways that cannot be effortlessly matched by Silicon Valley types through head-hunting and massive investment in data centres. Although we are living through a time of impressive technological development, it may well be that the AI race will not be won by the better technology. Particularly in the case of urban AI, it may be that what will matter is the ability of robots to learn about cities, and the ability of humans to design better ways to live in the city of multiple intelligences.

Thus, we come back to the value of the city as a testbed in the age of AI. Much of the talk about AI at the time of this writing is centred on GenAI and in forms of machine intelligence that rely on massive data centres where large language models are trained by reading pretty much every single bit of text available online. This is only a specific, narrow slice of what AI can be, and one that despite all its potential is also inevitably associated to various problems. When I think about GenAI in comparison to the forms of AI that would be used to support urban robots, one major issue with GenAI is that it relies in the kind of gargantuan data centre that I probably would not want to see in my city. A second issue is that Large Language Models trained on internet data are simply running out of new things to read. They have reached the point where they have read pretty much everything that has been written, and it is difficult for machines to learn and improve when they do not have access to new data… And that brings us back to cities. Machine intelligences are enormously data hungry, and cities (smart or otherwise) are endless sources of data. Also, importantly, deployments of urban robots such as those used by Starship demonstrate that one does not need super-human intelligences and massive data centres to have robots performing useful tasks and delivering useful services in an urban setting. Much of the debate about GenAI seems to be based on the assumption that such intelligences will soon match and exceed those of humans ( a PhD level intellect in your pocket!, or so they say). However, many mundane, repetitive or risky tasks that need to be done in cities could be done perfectly well with a level of intelligence comparable to that of, say, a reasonably clever dog. Put together, those points build up towards a conclusion that a city with some talent, some appetite for innovation and some willingness to learn to live with robots may well be in a position to effectively find translational pathways to create and capture value from AI in new ways that cannot be effortlessly matched by Silicon Valley types through head-hunting and massive investment in data centres. Although we are living through a time of impressive technological development, it may well be that the AI race will not be won by the better technology. Particularly in the case of urban AI, it may be that what will matter is the ability of robots to learn about cities, and the ability of humans to design better ways to live in the city of multiple intelligences.

Leave a Reply