As I settle into my role at the OU, I have been reflecting on what previous projects taught me about design research, particularly when it sits between disciplines. Before joining the OU, I spent several years working on interdisciplinary research projects at Lancaster University. One that has stayed with me is Desert Disorders, a British Academy funded project examining how the Thar Desert and Somaliland have been misunderstood through colonial and postcolonial lenses. Three professors across history, literature, and sociology collaborated across Lancaster university, Northumbria university, and IIT Delhi.

As design researcher, I analysed findings from three disciplines, synthesised data from historical archives, literary texts, and ethnographic fieldwork, co-facilitated workshops, and developed visual outputs for academic, policy, and community audiences.

The Project

The research was organised into three themes: Ecologies, Borders, Mobilities. Three professors with different methodologies needed ways to communicate their findings beyond journal articles, without losing rigour.

The challenge was finding patterns across disparate data, negotiating what mattered across disciplines, and creating outputs that facilitated dialogue rather than just presented conclusions.

Making Sense of Three Disciplines

I spent months with historical documents about Sambhar Lake’s salt production, colonial policy papers, ethnographic interviews with nomadic communities, and literary texts about desert mobility. My job was finding threads across ecology, borders, and mobilities that told coherent stories without flattening disciplinary differences.

I mapped recurring concepts and tensions across the research, traced historical arcs from 19th-century policies to contemporary crises, and asked – what insights need reaching beyond academia? Which narratives will resonate with policymakers? What will help communities see their knowledge valued?

Three Storyboards

The storyboards were one output among workshop materials, policy briefs, website content, and symposium presentations. They became particularly effective at translating dense research into something immediate.

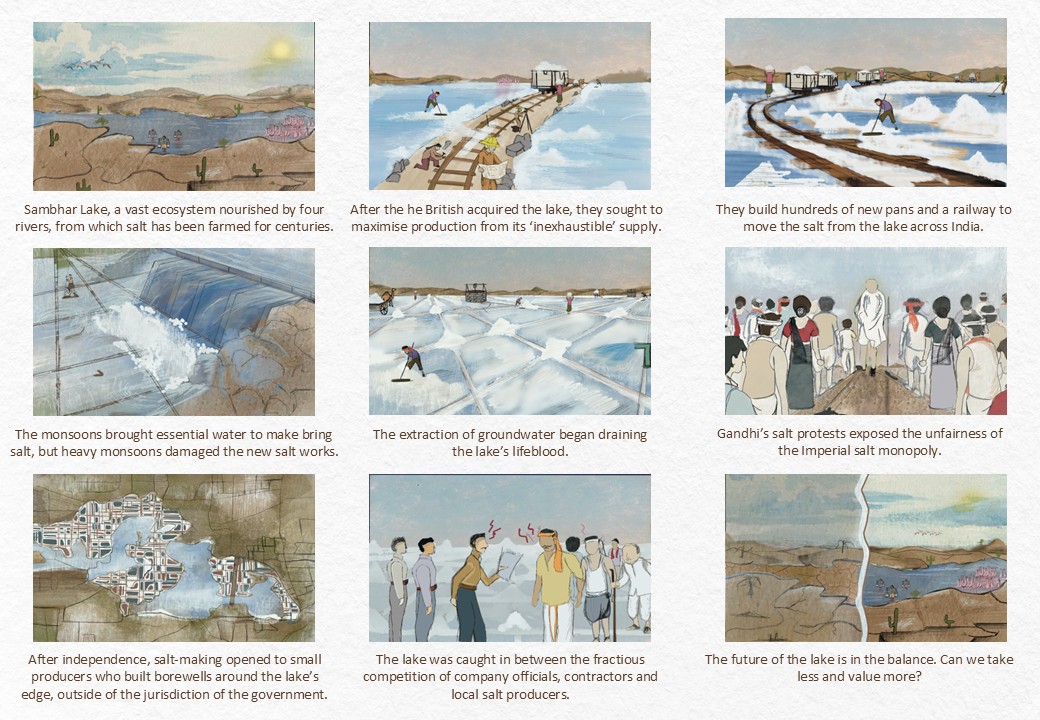

he Ecologies board tells Sambhar Lake’s story chronologically. Sustainable salt farming gives way to colonial maximisation of an ‘inexhaustible’ resource, then infrastructural damage, groundwater extraction, Gandhi’s salt march, and contemporary conflicts. Each panel distils years of research. The final frame asks: ‘Can we take less and value more?

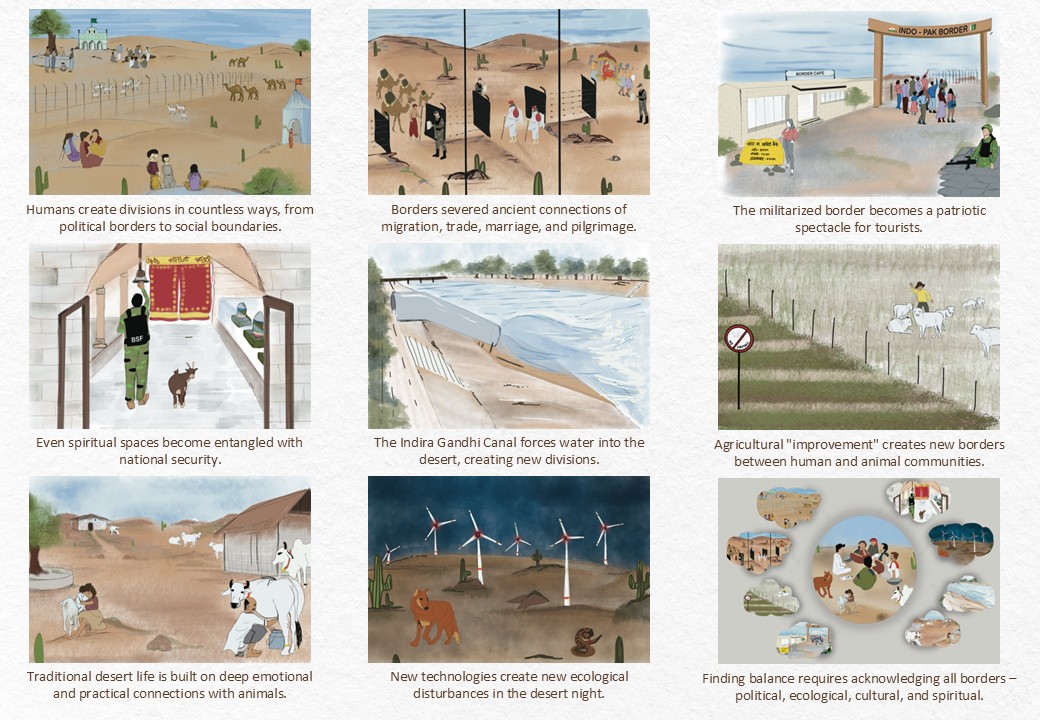

The Borders board visualised abstract concepts. How do you draw borders that aren’t just lines? I mapped multiple border types across the frames: political divisions severing ancient connections, militarised borders as tourist spectacles, spiritual spaces entangled with security, canals forcing water into deserts, fences dividing humans and animals, wind farms creating ecological disturbances. Each frame shows a different way borders operate in desert spaces. The final frame shows them all operating at once.

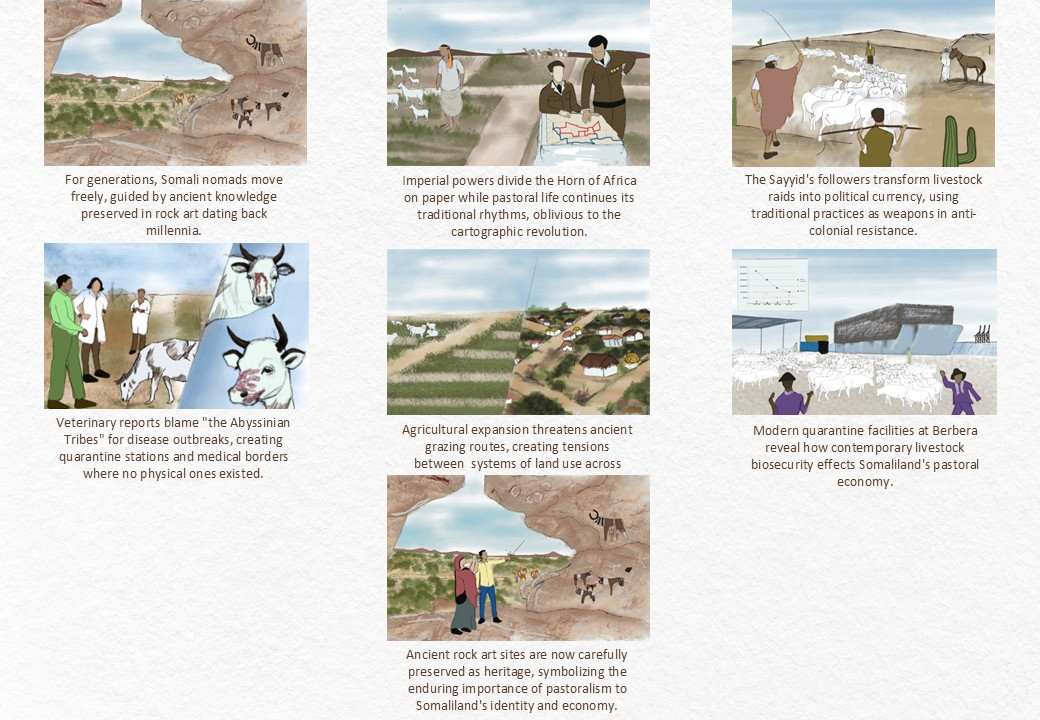

The Mobilities board traced the story of Somali nomadic communities. It started with ancient rock art guiding pastoral movement, then showed colonial cartographers dividing territory whilst that life continued, the Sayyid’s resistance using traditional practices as weapons, veterinary borders blaming tribes for disease, and quarantine facilities disrupting pastoral economies. It ended where it began with rock art, now preserved as heritage. Each image required asking: how do you represent freedom without romanticising? How do you show violence without sensationalising?

I hand-drew each panel, then digitised in Procreate. The design decisions were deliberate: watercolours and muted tones to ground the stories in desert landscapes, figures without caricature to show cultural specificity respectfully. These were not aesthetic decisions but rhetorical ones about how audiences would engage with the research.

My background complicated things as I am ethnically Rajasthani but have never lived in the Thar, only visited as a tourist. Analysing colonial extraction at Sambhar Lake whilst understanding why salt matters in every family ceremony added unexpected layers. In my family, salt is the first thing served with every meal. There is also an old saying about wasting salt, that in the afterlife, you would have to retrieve every grain you wasted, even those as fine as eyelashes. Reading colonial documents describing Sambhar Lake’s salt as “inexhaustible” whilst carrying this belief about accountability for every grain felt deeply dissonant.

Working on the Borders storyboard brought different reflections, growing up as a girl in a somewhat conservative community, I knew borders that were not on any map, invisible lines about where I could go, what I could study, who I could become. The Mobilities theme resonated too. Moving between India and the UK, between design practice and academic research, navigating different institutional spaces and cultural contexts, I understood something about the complex relationship between movement, belonging, and knowledge. Design research is supposed to be analytical, but some projects refuse to let you maintain complete distance.

Co-Design in Practice

The storyboards emerged through co-design with the three professors. Working across literary studies, history, and sociology meant negotiating what mattered most, which narratives connected, how to represent complexity visually. Each discipline brought different priorities. The co-design process worked through those differences, with storyboards as shared objects we could debate.

Then workshops with local charities, community organisations, practitioners extended the co-design beyond the research team. People engage with images differently. They point, question, add their stories. The storyboards became boundary objects, helping different stakeholders communicate across worlds and contribute perspectives.

Each feedback round meant reconsidering what stories needed telling, whose perspectives were missing, where we had oversimplified. The final versions went through community members in Rajasthan, scholars in Somaliland, policymakers in three countries. Design research is messy and iterative. The co-design process means outputs genuinely reflect multiple voices.

What Design Research Does

These storyboards have been presented at symposiums, used in policy workshops, shared across research networks. They opened conversations that academic papers alone might not reach and particularly powerful was the positive reaction from local communities and non-profits involved in the project, seeing their context shared with the world.

The academic contribution is not just the outputs but the co-design process itself: using visual methods to facilitate dialogue across disciplines, developing boundary objects that help different stakeholders contribute knowledge, creating research materials through genuine collaboration. The storyboards became spaces where historians, literary scholars, sociologists, community members, and policymakers could all see their perspectives represented and challenge what was missing.

The contribution is about how knowledge moves: between disciplines, between academic and public spheres, between abstraction and lived experience. The storyboards hold open questions rather than answer them: Can we value more whilst taking less? Can we acknowledge all borders, not just political ones? Can we honour ancient knowledge whilst building new futures?

That is what co-design contributes to interdisciplinary research. Not designers translating for others, but collaborative meaning-making. Not just pretty pictures at the end, but analytical and facilitative methods throughout. Ways of seeing patterns, synthesising across difference, and building knowledge together so it can travel across different worlds.

And sometimes, if you are fortunate, it helps you understand why salt has always mattered in ways you could not articulate before.

Leave a Reply