Having visited 78 Derngate in Northampton with students and tutors on the design courses last month, I was inspired to return to my studies of Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) and the Glasgow Four. 78 Derngate, a small terraced house near one of the old town gates, was originally built in 1815. The interior, extensively remodelled in 1916/17 by Mackintosh, was designed for colour-blind engineer, Bassett-Lowke, with Japanese inspired gridded black, yellow and white patterning; the only colours Bassett-Lowke could see. In some ways it was thus rather different to his more esoteric Scottish domestic interiors but an excellent example of how a designer addresses the needs of a client, whilst maintaining the aesthetic for which they were commissioned.

In Scotland, The Glasgow Four were often referred to as the ‘Spook School’, due to the ethereal elongated and possibly macabre forms within their work, however this has always made me wonder if there was something deeper in the background. ‘The Four’ comprised of Mackintosh, his wife Margaret, Margaret’s sister, Frances, and her husband Herbert McNair, all of whom had met as students at the Glasgow School of Art. Their work in architecture, graphics and the decorative arts was highly innovative, contributing significantly to what became a very distinctive Glasgow style. There is a spiritual intent behind their work, and not least in the design of Mackintosh’s domestic spaces. He would separate the ‘masculine’ areas from the ‘feminine’, keeping darker colours for the former, on the lower floors where visitors would be welcome and more cerebral activities took place, such as a library or study. Moving up into the more domestic private quarters, it got lighter and lighter, opening into white bedroom spaces, with furniture painted with layer upon layer of smooth eggshell paint that reflected the light and invited people to stroke them. White carpets completed the heavenly experience. Decorative elements, often created by Margaret, were organic, in keeping with the art nouveau aesthetic at the time, and revealed influences from Egypt, Japan, the Symbolists, and the Viennese Successionists.

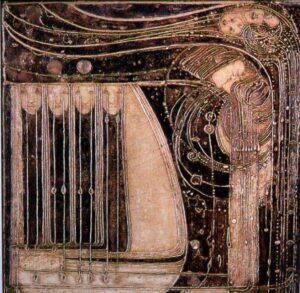

Working in Glasgow, Mackintosh and his associates were exposed to a wide variety of cultural influences, not least through imports arriving up the Clyde. Japanese goods started to appear in the west in the 1850s, and had gained enormous popularity by the end of the century. Mackintosh encountered Japanese design at Glasgow School of Art in 1884 and it became an inspiration throughout his career. Additionally, journals such as The Studio, Jugend, Ver Sacrum, and Pan transmitted artistic ideas across Europe, and the spiritual element to Mackintosh’s work chimed with cultural thinkers on the Continent. Design motifs and imagery in the graphic work of the group were mirrored by artists in Vienna, as seen below, and whilst Mackintosh’s modernist style was seemingly ahead of his time in the UK and not so enthusiastically embraced, his work was celebrated in Vienna. ‘The Four’ were invited to exhibit at the 8th Successionist Exhibition, 3 November – 27 December 1900, in Vienna, taking over Room X in Olbrich’s wonderful white Seccession building.

The work included furniture from the two couple’s homes, and gesso panels made by Margaret for Mrs Cranston’s Tea Rooms. It was well received by critics who noted the links to the Viennese designers’ work, and interestingly, the European reviews (there were none for English publications) also picked up on the ‘spooky’ aspect of the design and how it stood apart from contemporary British trends. Berta Zuckerkandl, for example, writing in the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung said, “The guests whom the Viennese artists have arguably taken most to their hearts are the Scots. Despite the difference in temperaments a certain linear affinity, a connection of colour ideals, cannot be denied. Here from the pages of the Studio, there from Ver Sacrum, the artists developed knowledge of their kinship. They aspired to artistic debate. The Scots appear distant from the English Arts and Crafts, curious and initially strange. They achieve a mystic, puzzling art. Their decorative motifs recall the mysteriously troubling imagery of India.”

W. Fred in Innendekoration, wrote of “the unsettling imagery and mood of the room” whilst in the Neue Freie Presse, Franz Servaes said that “with Mackintosh one is reminded of ascetic, pious and mystic sects.” Whilst artists and designers in Vienna might have been inspired by what they saw, they were aware that for the general public, the Glasgow style was more of a challenge. In the Wiener Rundschau it said that “the Mackintosh room is the most advanced yet of all experiments in the field of modern interior decoration. This is proven by, among other things, the irritated bewilderment of the public and their journalistic spokesmen. Here all extremes are reconciled, America and the Bukovina are united. Their antipathy towards Mackintosh arises from the accurate feeling of being threatened at their essence … Modern spirituality … comes into their homes and threatens [their] comfort and as a result there are complaints about spooky rooms and such like.”

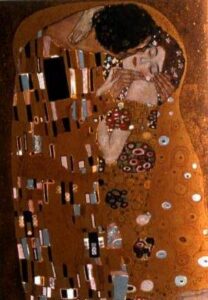

The undercurrent of mysticism hasn’t been fully investigated, not least the possible links between the work of the Glasgow Four and Theosophy, a mystic religious, or occultist movement that had been started in the United States in the later 19th C by Russian born Helena Blavatsky. It’s complex in its thinking, drawing together Eastern and Western theologies and philosophies, with the goal to find universal truths. Similar to Buddhism, it believed in the concept of reincarnation, where, through a succession of lives, a human would gain virtue and wisdom until ultimately unity was achieved with the Universal Spirit, rather like achieving Nirvana. At a time of enormous change and continuing high rates of mortality, it’s not hard to see how such a philosophy could take hold. Many Victorians were already fascinated by the occult and trying to find ways of communicating with their lost loved ones. Death was romanticised and fetishised in literature and art. Theosophy thus gripped the imagination of many artists throughout Europe, not least the Symbolists and the progenitors of abstract art.

The first Theosophical Lodge in Scotland was established in 1884 in Edinburgh and the first in Glasgow in 1900. Interestingly, the Glasgow School of Art had appointed the Belgian Symbolist, Jean Delville (1867-1953) as head of painting in 1900. This seems quite an unusual choice. Delville was a theosophist and his works, certainly in his early years, explored spiritual themes, including ideal love (something that can be seen in the work of Margaret MacDonald but also in Mackintosh’s design aesthetic that merged the feminine with the masculine, light with dark, organic curves with hard angles and lines), and death. He believed materialism and the physical human body could imprison the soul; we should aspire to operate on the higher astral and divine planes. He had become immersed in theosophy in the second half of the 1890s, and with the publication of his book, The New Mission of Art the year he arrived in Glasgow, which focused on his spiritual views, it is very likely that Mackintosh would have been well aware of him and his work. I would love to know more!

References:

78 Derngate: The Charles Rennie Mackintosh House – 78 Derngate

Mackintosh Architecture: Context, Making and Meaning Mackintosh Architecture: Context, Making and Meaning (gla.ac.uk)

Art Nouveau Magazines: ART NOUVEAU MAGAZINES – (theviennasecession.com)

Leave a Reply