I am currently running a survey trying to understand people’s perceptions of different aspects of comfort in multiple types and ages of homes in the North of England and the Scottish Borders, from 15th century cottages to Passive Houses (and if you’re in this area and want to fill in the survey you can find it here!). When explaining this to some friends a few weeks ago they said: ‘What do you mean by comfort?’

I explained that what I meant by comfort included a range of aspects that are generally considered to be affected by buildings. These include:

• Thermal comfort – whether they think their home is hot or cold

• Visual comfort – whether indoor conditions are bright or dim

• Audio comfort – whether internal and external noise levels are quiet or noisy

• Whether building conditions are damp or dry

• Whether people think their indoor air quality is good or bad (although humans are very poor at identifying air quality issues)

All aspects but audio ask respondents to separately consider conditions in winter and summer and importantly participants are not only asked how they perceive these aspects but also what if any changes they would like. So, for example, if they have said that their home is currently ‘cool’ would they like it to be warmer, cooler or remain the same?

This is important as it implies a lot about why certain conditions are thus in their home. Especially with temperature, some people may say that their home is cool in winter but that they are happy with current conditions.

Comfort is a very personal and subjective quality that can vary substantially. Something that everyone needs to remember when designing standards for indoor environmental conditions in buildings!

Just because someone only heats their home to 16ºC doesn’t necessarily mean that they can’t afford to heat their home more, it may be an active choice, and they are happy to wear (Christmas!) jumpers. Equally, depending on personal circumstances such as age and health and background, someone else may be wearing three jumpers and a woolly hat and still be cold at 20ºC and need support to improve conditions.

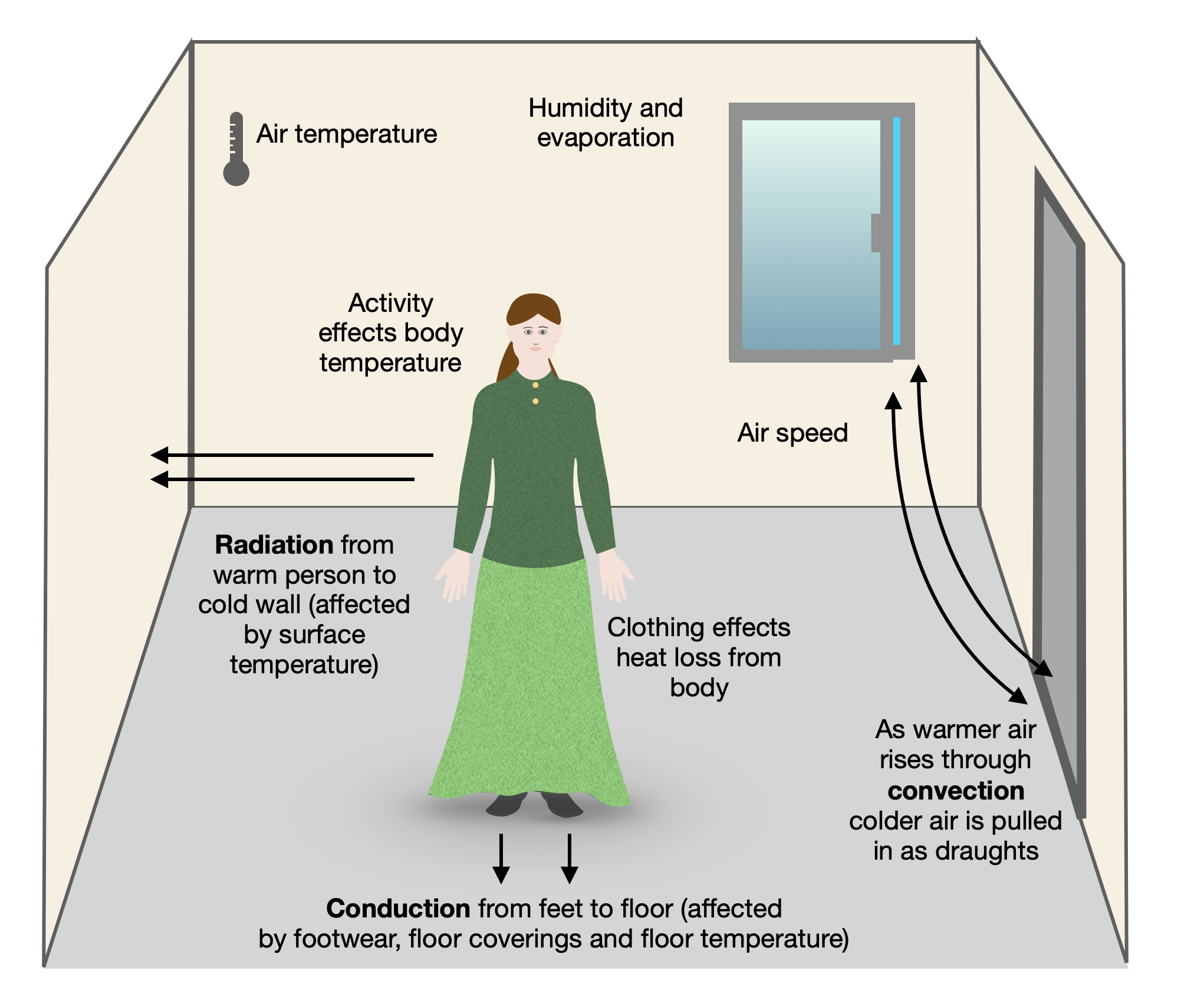

Thermal comfort is affected by more than air temperature; it depends on drafts and air movement, humidity, surrounding surface temperatures, levels of activity and clothing, size of the space, etc, etc, etc…

This is how comfort is generally thought about in the built environment research field. But my friends’ question made me think in a broader sense, about what comfort is, how many other things effect it and how both individual and psychological it is.

For example, there is research suggesting that people feel warmer if they have a screensaver of a roaring fire, or if their décor is a ‘warmer’ colour. Likewise, we talk about ‘cool’ colours in warmer climates. Comfort more broadly is also affected by someone’s sense of security in a space as well as the activities they are expected to do and who they are in company with.

These aspects are obviously a lot harder to measure, much more variable than some of the physical metrics and move into what is considered the aesthetic field and personal preferences which are less susceptible to standardisation. They are therefore often not considered in assessments of comfort in the built environment (which also often focusses heavily on thermal comfort).

However, they are very important for our wider understanding of comfort in buildings, and I would argue should receive more consideration than they currently do in built environment research. This is particularly as we seek to design ways to adapt our buildings so that they can provide better comfort with lower carbon emissions and adapt to changing climates.

At the end of the day, there is little evidence for a universal, healthy or comfortable indoor temperature (maybe the subject of another blog!) so we should rely not only on technical measurements but also on people’s perceptions to understand comfort more holistically.

Now, I’m off to decide if my red or my blue jumper will be warmer for Christmas…

Leave a Reply