Bringing people together to solve heritage greenspace challenges

Anyone managing a heritage site knows the headache. You have got Victorian gardens that need preserving, climate targets that need meeting, communities that need access, and budgets that never stretch far enough. How do you juggle it all without dropping something important?

We had quite a day at The Crichton Trust in Dumfries back in August. Heritage managers, community representatives, researchers, local authority planners all crammed into one room trying to figure out why heritage greenspaces struggle so much with environmental goals and community needs.

The Crichton Trust had laid on amazing scones for breakfast, and we were blessed with one of those perfect (and elusive) Scottish summer days, nearly 25 degrees and brilliant sunshine. Not exactly what you expect from late August in Dumfries, but we were not complaining.

The thing is, everyone knows heritage green spaces have massive potential. The Crichton estate itself is a perfect example, 85 acres of heritage parkland, home to universities and 160 businesses, open 24/7 for the community. But like so many heritage sites, they are wrestling with how to balance conservation requirements with ambitious environmental targets. Do you prioritise the historical integrity, the climate goals, or focus on the community and their wellbeing? Turns out, maybe that is the wrong question altogether.

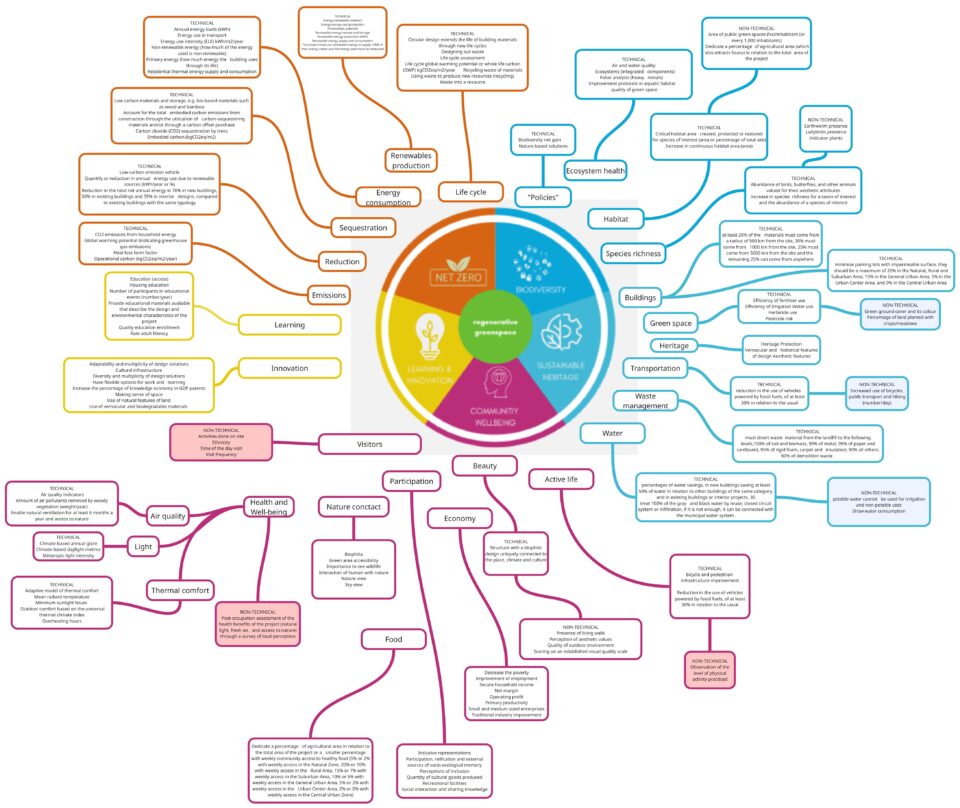

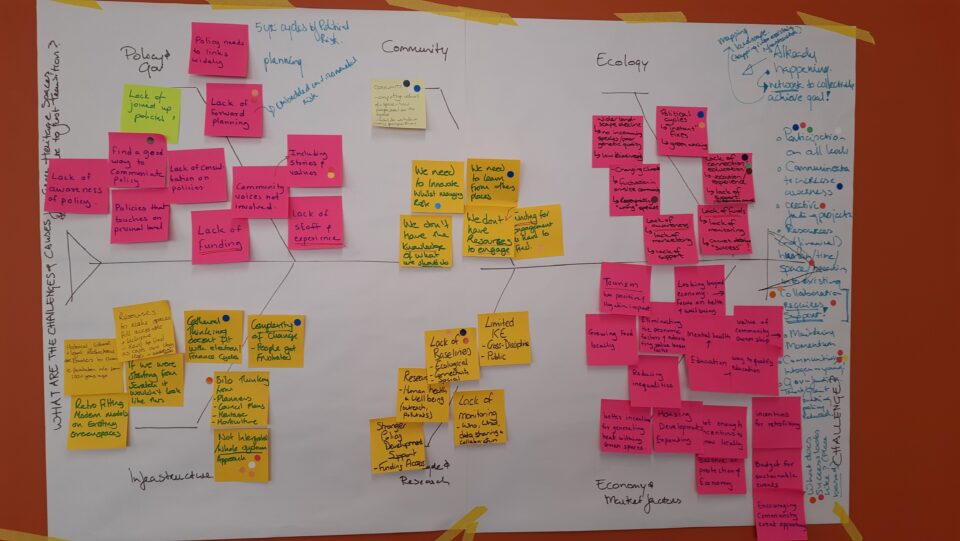

This was our second workshop. Back in July, we had spent a day with some of the same people working through definitions and imagining regenerative futures. Simone Farris, our research associate, had mapped all his findings from the literature review and previous workshop into Miro, creating a fantastic visual foundation for our ongoing work. But rather than jumping straight into solutions (which let us be honest, we all wanted to do), we started with something that felt a bit like detective work. Jennifer Challinor had suggested using the Fishbone analysis method. It is borrowed from quality management, not exactly what you would expect in a heritage context, but it works.

Digging into what is actually wrong

The groups worked through six areas where things go sideways: policy and governance, community and social factors, environment and ecology, infrastructure and resources, knowledge and research, and economic pressures.

What came out was revealing in its specificity. On the policy side, participants identified embedded unconnected risks in planning systems, a lack of forward planning, and policies that focus on personal-level changes rather than systemic solutions. The community challenges were stark: “We do not have financial resources” appeared multiple times, alongside concerns about community voices not being heard and limited genuine participation.

Infrastructure problems ranged from retrofitting existing buildings to the fundamental challenge that there are no accessible principles for how to manage heritage green spaces. One group noted the tension that “economic implications are limiting ways to measure” success, while another highlighted how the physical layout of many heritage sites creates barriers.

The environmental findings were equally sobering. Participants identified green-washing and lack of systems thinking, community resistance to visual changes, and fundamental questions about whether heritage sites should focus only on native species or embrace their ornamental heritage.

But here is where it got interesting. Using the “Five Whys” technique (a method adapted for policy work by colleagues at Policy Wise at the Open University with their Wise in 5 framework. Groups traced problems back to their systemic roots, revealing how surface-level issues often stemmed from deeper policy failures or structural inequalities.

Actually writing policy together

After a lovely lunch arranged by the Crichton Trust café, Jennifer Challinor took us on a walk around the grounds. With the gorgeous weather, it was the perfect opportunity to see the historic building, heritage trees and surrounding parkland we had been discussing all morning. There is nothing quite like experiencing the space you are trying to understand. Walking around those 85 acres in 25 degrees sunshine really brought home both the potential and the challenges we had been mapping out.

The afternoon session took inspiration from Policy Lab Scotland’s “Policy Lab in a Day” approach, bringing diverse groups together to co-create policy solutions in compressed timeframes. Mixed groups, combining different expertise, each tasked with writing specific sections of an actual policy brief.

We used a template to work from which used the key findings from our mornings fishbone work, as well as an introduction laying out the challenge, policy recommendations, and a call to action. Groups focused on different themes, one tackled net-zero approaches, another worked on community wellbeing, and others on governance structures.

What emerged was remarkably concrete. The biodiversity group developed recommendations around making conservation “measurable” and creating dedicated community park rangers at local and national levels. They emphasised place-based approaches to education and called for more ambitious, long-term government thinking. The community wellbeing team focused on heritage parks as “untapped potential” for physical, mental and social health, emphasising the importance of spaces that create belonging through connection to nature, heritage, and others across generations.

The net zero group got into specifics: carbon-neutral infrastructure with policy support for green transport, sustainable building design with flexible planning regulations, on-site renewables with proper incentives, and, crucially, developing skills to support the carbon-sink potential of heritage green spaces. They were clear that “offset is the last resort.”

The energy in the room changed. Instead of talking about problems, people were problem-solving with real recommendations. A community organiser was helping a heritage manager think through governance structures. A researcher was working with a local authority planner on monitoring systems.

Making connections

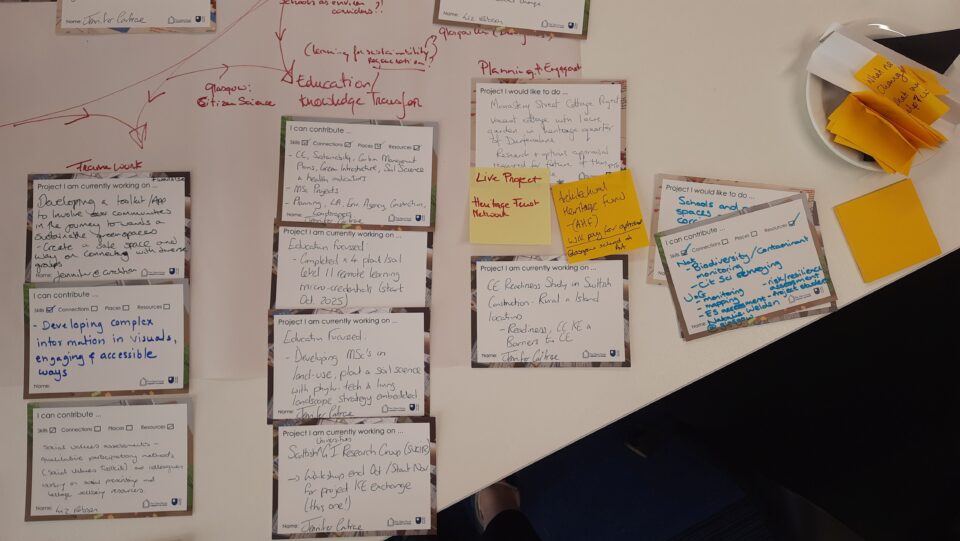

Using the cross-pollination approach developed by the research partnership the Open University Design group with the Glass House Community-Led Design, the last workshop was a process designed to ‘fostering innovation and collaboration by connecting diverse groups and sectors to share assets, ideas, and resources to create new projects and enhance existing ones’. It supports placemaking by bringing together people from different sectors (community, business, government, academia) to share assets such as skills, resources, and ideas through workshops, so they can collaborate more effectively to shape local places.

We followed three simple steps: First, people wrote down projects they are already doing or want to do (one per card, please!). Second, they identified what they could contribute: skills, networks, resources, local knowledge. Third, they just… connected. Cross-pollination in action.

Sounds simple, yet watching it happen was quite something. People were discussing their project cards with similar ones, placing their “I can contribute” cards next to projects that interested them. A community heritage group mentioned their knowledge of local history, and suddenly an ecologist realised this could be crucial for understanding why certain restoration approaches might work or fail in specific locations. Someone working on innovative financing models connected with a heritage manager looking for new funding approaches.

What emerged were potential research collaborations around citizen science approaches to biodiversity monitoring, innovative financing models for heritage conservation, and educational programs that use heritage sites as sustainability learning labs. By the end, people were already talking about follow-up meetings and shared funding applications.

The wealth of expertise in the room was striking. The problem is not capability; it is that everyone is working in parallel rather than together.

What actually worked

The structured approach prevented us from falling into the usual patterns. Instead of immediately jumping to “we need more funding” (which, yes, everyone does), the Fishbone analysis forced us to look at systemic issues. The policy brief format kept recommendations practical rather than wishful thinking.

But honestly, the most valuable thing might have been simply getting these different sectors talking to each other. Heritage managers and environmental researchers do not usually end up in the same workshops. Community advocates and local authority planners often see each other as obstacles rather than potential collaborators.

For anyone thinking about trying something similar, a few things seem essential: give people time to actually get to know each other, make sure you have genuinely diverse representation from the start, use someone skilled at group facilitation, and plan proper follow-up. These conversations need to continue beyond the workshop.

What happens next

The collaborative process created something concrete. People exchanged contacts and scheduled follow-up meetings. We committed to refining the policy brief and sharing it with participants by the end of October. Research collaborations were already forming around the themes that emerged.

But the workshop also generated very specific action points. The groups were clear that effective change needs to “start at the government level” rather than relying solely on local initiatives. They emphasised the need to lobby MSPs (Members of Scottish Parliament) and engage with the political process. And yes, they specifically called for writing blogs to share insights and mobilise wider support, which is exactly what this post is doing.

The collaborative process established a shared language between sectors that usually operate in separate worlds. Heritage managers, researchers, community advocates, and policymakers are working on similar challenges but rarely talking to each other. The systematic approach (fishbone analysis preventing us from jumping to familiar solutions, policy brief format keeping recommendations practical, cross-pollination revealing unexpected synergies) created space for genuine collaboration.

For anyone thinking about trying something similar, a few things proved essential: allowing time for people to actually get to know each other (those coffee breaks and Jennifer’s garden tour mattered), ensuring genuinely diverse representation from the start, having skilled group facilitation, and planning proper follow-up. These conversations need to continue beyond the workshop, and having concrete commitments helps make that happen.

Heritage green spaces are facing serious pressure from climate change, development demands, changing community expectations. But this workshop suggested that maybe the path forward is not individual organisations struggling alone but building genuine collaboration across sectors.

Which, when you think about it, is probably how most complex problems get solved anyway.

The regenerative heritage greenspaces project is supported by The Open University’s Open Societal Challenges programme in partnership with The Crichton Trust.

Leave a Reply