I recently had the opportunity to attend The Bad Conference, part of Product Design Week #PDW23, organised by Tech Circus in London. The turnout for the in-person event was impressive, with 250 individuals joining in person. Networking, an essential part of such gatherings, felt notably different post-Covid. Rather than the fluid mingling of the past, there was a tendency for people to stick within their familiar circles, perhaps a sign of the lingering effects of the pandemic. As someone who tends to arrive early, my pre-event interactions have shifted; previously, it meant engaging with fellow attendees, but now it grants me time to gather thoughts and start jotting down notes.

Tech Circus, originating eight years ago in a pub setting, has evolved from organising simple meetups to curating conferences centred around UX in Technology. This year marked an ambitious consolidation of diverse conferences into a week-long event. The first day was dedicated to Behavioural Design, merging psychology with design—a topic perfectly aligned with my interests, blending practical insights with academic depth. Below, I outline the ten talks that were part of this event.

Talk 1: Democratising Human and Science-Centred Design

Rosie Webster, a self-proclaimed “Recovering Academic” who transitioned from academia to industry, brought an insightful perspective. Working in Applied Behavioural Science and User Research at Zinc VC, she emphasised the criticality of applied science in design. Webster highlighted the abundance of valuable research often locked behind paywalls or overlooked due to a lack of awareness.

Her presentation focused on merging Human-Centred Design (HCD), the gold standard in Product Design, with Behavioural Science-led Design. According to her, this fusion amplifies both disciplines. Behavioural Science offers a deeper understanding of human behaviour, expediting insights into behaviour change, while HCD ensures products address user problems effectively and are engaging.

Webster emphasised the need for incorporating science into User Experience (UX) processes. While primary research remains essential, leveraging existing scientific research can augment knowledge and problem-solving. She referenced instances like the pandemic, where rapid literature reviews became crucial due to the absence of relevant research.

She advocated for frameworks like the COM-B Method, especially for tackling the complex task of changing motivations. Additionally, Webster stressed the significance of using evidence-based techniques and interventions, pointing out the underutilisation of academic research in industry practices.

Webster’s talk underscored the necessity of amalgamating science and design to leverage existing knowledge, employ evidence-based practices, and measure effectiveness for optimal product design and user engagement.

Talk 2: Engaged! Immersive Research Methods and Experiences

Souleymane Camara, from BP, highlighted the challenge of integrating design methodologies within large, traditional organisations. He emphasised the significance of gaining stakeholder buy-in for design initiatives. Camara advocated for immersive research experiences as a powerful approach to showcase user problems directly to stakeholders and demonstrate how design can offer solutions.

He began by defining immersive user research methodologies, emphasising the need for close observation and active engagement with users within their authentic environments. The goal is to gain deep insights into user pain points and unmet needs and unearth opportunities for innovative and compelling human experiences.

Camara stressed the challenge of simplifying academic research for stakeholders and persuading them about the significance of user research. He emphasised cultivating a human experience mindset in UX research, emphasising empathy, active listening, and considering the holistic user journey while addressing ethical considerations.

To make research more engaging, he highlighted the importance of avoiding mundane presentations and instead focusing on immersive experiences. Stakeholder engagement, according to Camara, is crucial as their diverse perspectives on business goals, user needs, and technical constraints inform informed decisions based on user insights and business considerations.

The speaker presented examples like Airbnb’s host immersion program, Ford’s in-car ethnography, and experiences with brands like Itsu and Ikea, showcasing how immersion aids in understanding user experiences. He detailed BP’s strategies, including EV Safaris, concept experiments, rapid discovery playback, mixed reality (VR), and employing digital twin technology, all aimed at transforming stakeholder engagement through immersive experiences.

Camara concluded by emphasising the necessity for researchers to advocate for research within their organisations, acknowledging the difficulty in democratising research and instilling a similar thinking model among stakeholders. The talk highlighted the importance of immersive research methods in engaging stakeholders, leveraging empathy, and fostering a deeper understanding of user experiences to drive impactful design solutions within large corporate environments.

Talk 3: In-person versus remote research – how to use the best of both for richer and more impactful behavioural data.

Adel Kalman, an experienced user researcher at EE, shed light on the evolving landscape of research methodologies, particularly the dominance of remote research in the post-COVID era. Kalman emphasised the enduring presence of remote research and its advantages: convenience, speed, wider participant accessibility, reduced geographical limitations, enhanced safety, and cost-effectiveness.

The talk delved into the “mode effect,” highlighting differences in responses based on varying questioning methods. The choice between in-person and remote modes depends on factors like the degree of interview involvement, contact with respondents, communication channels, locus of control, privacy, and technology.

Kalman cited examples showcasing the mode effect’s presence or absence, demonstrating instances where web surveys garnered more honest responses, particularly in post-COVID times, where virtual interviews facilitated greater comfort in answering personal questions.

However, the discussion pondered whether more information necessarily equates to better information. While remote settings often encourage sharing sensitive information, the nuanced cues and personal connections in in-person settings remain crucial, especially in emotionally challenging conversations. In-person research, though demanding in planning, can be more suitable in such scenarios.

The session underscored that while remote research is comparable to in-person in terms of data quality, there are times when in-person interactions yield superior impact, especially in understanding non-verbal cues and navigating emotionally sensitive topics.

Kalman emphasised the team-oriented nature of impactful research, highlighting the essential roles of participants, user researchers, and observers (product managers, design leads, tech leads). Involving stakeholders in the research process bridges the gap between users and the company, enhancing the research’s impact on product development.

In conclusion, the talk recommended leveraging remote research for sensitive insights while balancing it with in-person methodologies like lab installations. Encouraging stakeholder involvement, valuing nonverbal observations, and recognising the distinctive impacts of various research modes were highlighted as key takeaways for effective research strategies.

Talk 4: Prioritise impact through design.

Valeriya Azorina, a senior UX researcher at Prolific, shared insights into a methodology for prioritising projects to maximise impact and prevent overwhelming workloads that could potentially downgrade the strategic significance of User Experience Research (UXR) within an organisation.

Azorina highlighted the need for a roadmap to predict upcoming research work, enhance accountability, aid resource planning, collaborate with stakeholders, and ensure transparency. Their approach involved holding biannual one-hour workshops, inviting key stakeholders such as project managers, designers, and researchers. They brainstormed and prioritised research projects using whiteboarding tools, filtering out non-research-related tasks through a prioritisation matrix.

During these workshops, they estimated the time and impact of each project, aligning outcomes with team objectives. This process resulted in a clear vision of research results, ensuring their usability, validating estimated impacts, and guiding the creation of appropriate deliverables. Critical questions were posed to assess the impact and decision-making potential of the research output, aiming to define the current perception of research within the organisation.

Over the two years of implementing this process, it facilitated project sizing capacity planning and reinforced team rituals like newsletters and communication planning. This approach also enhanced predictability, justified focusing on impactful research, engaged research leadership, and instilled a sense of accomplishment within the team.

Key tips included acknowledging organisational uniqueness, adapting the process based on identified challenges, iterating based on feedback, and not neglecting maintenance. They emphasised the importance of keeping a list of “won’t do” projects to understand growth opportunities for the team. Azorina stressed the significance of involving the team to aid their understanding of priorities and delineate why some projects might not proceed. Additionally, she highlighted the challenge of foundational research often being side-lined for more tactical activities, urging a balanced approach.

In essence, the collaborative research roadmap approach advocated by Azorina aims to align research projects with strategic objectives, enhance accountability and transparency, and ensure that UXR efforts yield impactful outcomes for the organisation.

Talk 5: The Decline of Nudge Theory

Nazima Kadir, a Lead Senior User Researcher at J.P. Morgan, provided insights into nudge theory, contrasting it with anthropology, her area of expertise. Nudge theory, rooted in behavioural economics, promotes soft interventions that influence behaviour without restricting options. It gained prominence through Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s book “Nudge,” advocating for choice architecture to guide decisions without limiting freedom.

Kadir questioned the excessive focus on individual behaviours, favouring a broader anthropological perspective that acknowledges diverse cultural behaviours. She highlighted how nudge theory has been popularised in public sectors globally, impacting policies and political ideologies. However, Kadir criticised the theory’s limitations, emphasising that changing environments might be more ethical and sustainable than solely focusing on altering individual behaviour. She cited examples such as incentivising savings without addressing systemic issues like stagnating wages and financial illiteracy. The critique extended to nudge theory’s application in UX and design, where it encourages specific behaviours, often neglecting broader systemic changes. Kadir expressed concerns about the over-reliance on individualistic solutions in health, finance, and digital design, emphasising the necessity for systemic changes.

She advocated for a shift from individualistic solutions toward systemic changes, criticising the narrow focus on individual behaviour and the potential harm caused by well-intentioned interventions. Kadir proposed a more humanities-centred design approach that considers global-scale impacts while not overlooking the positive aspects of nudge theory and Human-Centred Design (HCD).

In essence, the talk highlighted the limitations of nudge theory in addressing complex societal issues and urged a broader perspective focusing on systemic changes over individualistic solutions. Kadir emphasised balancing these approaches to achieve meaningful and impactful transformations.

Talk 6: Shifting from industry standard persona development to behavioural personas with the use of mixed data and behavioural science.

Elena Hill-Artamonova, a Doctor of Psychology and Statistics at Mention Me, addressed the limitations of Standard Personas in design, emphasising their reliance on assumptions and generalisations that often inaccurately represent user behaviours and motivations. She introduced Behavioural Personas as an alternative approach to research and analysing user behaviours, integrating qualitative and quantitative data to create more accurate representations.

Behavioural personas diverge from traditional personas by focusing on understanding user mindsets, behaviour patterns, and motivations derived from comprehensive user research. Hill-Artamonova stressed the importance of these personas in providing detailed insights into user interactions with products or services, especially in cases where User Researchers (UR) might not directly engage with customers in B2B scenarios.

The adoption of behavioural personas in UX research offers several benefits. They enable designers to craft more targeted and personalised user experiences by aligning design decisions with user needs, pain points, and motivations. However, transitioning from traditional personas to behavioural personas might pose challenges in theory application and practice.

Developing effective behavioural personas involves employing diverse research methods such as contextual inquiries, diary studies, observations, and analysing quantitative data. These methods facilitate a comprehensive understanding of user behaviours and aid in creating more accurate personas, helping avoid the need for frequent revisions. Key research methods highlighted included in-depth user interviews for insights into motivations, usability testing for authentic behaviour observation, and data analytics to uncover behavioural patterns.

In conclusion, adopting behavioural personas offers a more in-depth understanding of user behaviours, providing a 3D image of customer behaviours, attitudes, and experiences. These personas focus on psychological drivers, aiding in creating robust customer journeys that cater to both practical and emotional needs, ultimately leading to greater personalisation of user experiences.

Talk 7: Psych-n-Cyber presents: Let’s talk about Behaviour Science and online safety.

Dr Inka Karppinen, a Cyber-Psychologist and Lead Behavioural Scientist at Cybsafe, delved into the intersection of behavioural science and online safety, emphasising that almost every design intended for user interaction involves some level of behaviour change. She quoted Amy Butcher, highlighting the core aspect of behaviour change inherent in product interactions.

Karppinen underscored the critical role of psychology in addressing cyber threats and crimes, pointing out the lack of attention to security, cognitive biases, manipulation techniques, and the impact of emotions. She highlighted the online disinhibition effect, shedding light on the vulnerabilities and human elements that cybercriminals exploit. The staggering statistics she shared — 3.3 million fraud victims, with 74% involving a human element — emphasised the magnitude of cybercrime and the sophistication of cybercriminals, often leveraging psychological tactics effectively.

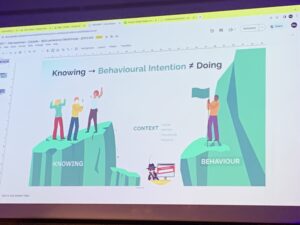

She criticised the prevalent approach of organisations that focus primarily on mandatory phishing simulators and awareness campaigns in the news, questioning their efficacy. Karppinen revealed that less than 15% of individuals change their behaviour after routine training sessions, emphasising the gap between knowledge and behavioural change.

Looking to the future of cybersecurity, she posed essential questions about designing for cybersecurity, highlighting the need to consider diverse user groups, including people with disabilities, learning difficulties, visual impairments, and varying technical knowledge levels. Karppinen emphasised the importance of designing solutions that are inclusive and accessible to all users, acknowledging the potential scam risks associated with every new technological solution.

Talk 8: What infiltrating cults taught me about ethical design.

Patrick Fagan, former Cambridge Analytica psychologist and author of “Free Your Mind,” shared insights from infiltrating cults, multilevel marketing schemes, and online forums. He discussed how psychological manipulation techniques used by these groups shed light on ethical behavioural design practices.

Fagan highlighted nine principles based on his experiences:

- Bamboozle: Cults must first disarm the conscious ‘watchdogs of the mind’ and disintegrate the old. They might exploit tiredness, stress or turbulent life changes. They might overwhelm people with drums, intoxicants or snake handling. So yes, disrupt the users’ old patterns of behaviour and shake them out of it, but don’t exploit the fact they might be tired or confused.

- Rationalise: we tend to post-rationalise our behaviours and thus cement our habits and beliefs even further, even if they are wrong. Cults often have complex rabbit holes of intellectual thought that keep people trapped. So yes, give users rational explanations for target behaviours. But don’t lead them down intellectual rabbit holes.

- Attachments: Nature abhors a vacuum. People who are missing purpose in life are more likely to be swept away by some kind of ideology. Cults seek people who are lost, cut them off, and love bomb them into a new family and mission. So yes, give users the chance for community and busyness. But don’t exploit vulnerability or overstate purpose.

- Increments: Indoctrination rarely happens overnight. Instead, it is the cumulative effect of gradual changes. Cults typically get adherents to make small commitments at first, ramping up the investment over time. So yes, tunnel complex actions down into simple steps. But don’t hide nasty surprises until the end of the journey.

- Norms: We are hardwired to follow the crowd and to follow authority. Cults leverage our desire to conform and establish strong social norms (even their own judiciary) whose violation would lead to painful ostracisation. So yes, highlight when an action is popular or endorsed. But don’t stretch the truth or make people feel left out.

- Wishes: Propaganda is 50% the message and 50% the audience. It usually can’t create new desires but rather acts as a lightning rod for what is already repressed. Cults exploit the needs and greeds of those who are not careful what they wish for. So yes, appeal to your audience’s unique motivations, but don’t underdeliver on your promises, and don’t be too invasive.

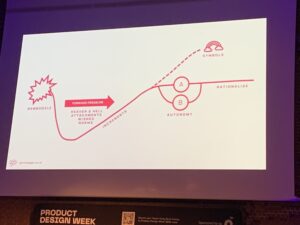

- Autonomy: You can’t push a donkey from behind, and people show reactance if a cult tries to force them to do something. Instead, they foster the illusion of choice and control the choice architecture, often with false binaries. So yes, respect the users of autonomy and simplify the choice set. But don’t nudge them towards choices they didn’t want.

- Symbols: Symbols are a physical expression of an invisible ideal that is hard to put into words. They act as a conductor for shared experiences and emotions. Cults use symbols to galvanise people around a common community and behavioural goal. So yes, harness the power of cultural capital and make things intuitive. But don’t manipulate people on a level they might not notice.

- Heaven & Hell: Cults drive behaviour toward a particular end by painting a vivid picture of the disastrous outcomes of inaction (or the terrible present) as well as the utopian version to be achieved through compliance. So yes, sell uses a fantasy and reward desired behaviours. But don’t shame or punish; use assurance not loss aversion.

Fagan cautioned that individuals with higher intelligence are more susceptible to rationalising cult-like behaviours. He emphasised the ethical use of nudge techniques, advocating for their application in changing stakeholders’ thinking while adhering to ethical principles.

Talk 9: Jobs-to-be-done: a framework for product discovery influenced by behavioural design.

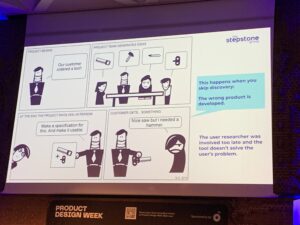

Sabrina Duda highlighted the critical role of product discovery within the design process, focusing on the Jobs-to-be-Done (JTBD) framework implemented by The Stepstone Group. The approach to discovery comprises understanding both the problem space and the solution.

Discovery has two stages:

- Problem Space Discovery: This involves delving into user problems through research methodologies like Discovery Research and the Jobs-to-be-Done approach. Identifying the exact problem the user faces is crucial.

- Solution Discovery: Once the problem is understood, the focus shifts to discovering solutions through design sprints, prototyping, and concept testing. The aim is to solve the identified user problem effectively.

The JTBD framework, rooted in Theodore Levitt‘s idea from 1983, emphasises that users don’t buy products; they “hire” products to fulfil specific jobs or needs. For instance, Netflix isn’t just a digital service; its job is to facilitate ‘relaxation’. Viewing it through this lens broadens the scope of competition; instead of merely comparing it to other streaming services like Disney, it might compete with activities like ‘exercising’ or ‘socialising’.

The framework follows a sequence: research, activation, and implementation, remaining agnostic to specific products or industries, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of user needs and desires. This approach ensures the solutions address the users’ underlying problems or goals, fostering more effective product development.

Talk 10: Unlocking Healthcare Innovation: Behavioural Design for Technology Adoption, AI Explainability, and decision-support in Clinical Practice

Maura Bellio, a Senior Clinical UX Designer at Medtronic, delved into the significant gap between AI innovation and its practical application in healthcare, which she terms the “Design-Reality Gap.” She highlighted AI’s potential for revolutionising healthcare, driven by the vast availability of Big Data, enhanced computational power, and the ability to discern patterns invisible to the human eye. AI can immensely support clinical tasks like diagnosis, treatment selection, and prognostic predictions, particularly in areas like interpreting X-rays.

However, a critical hurdle lies in the complex nature of AI interfaces, often designed by technical experts. These interfaces tend to be too intricate for clinicians, hindering the widespread adoption of AI in healthcare settings. Maura outlined common challenges in a typical hospital scenario: messy clinical data, time constraints, socio-technical factors, and the tendency to abandon technologies due to usability issues.

One primary issue she emphasised is the lack of Human Factors considerations in the development of AI-driven tools for healthcare. This results in an adoption gap akin to a canyon. Some critical challenges include oversimplification and miscommunication of scenarios, inadequacies in clinical relevance despite algorithmic significance, and the need for explainability, trust, and transparency.

Maura highlighted new design questions, including addressing inconsistency and unpredictability and ensuring contextual fit within the healthcare setting, considering terminologies, resources, time pressures, and workflow factors. The need for decision support systems integrating AI for automation, prediction, and diagnosis remains clear. However, for these systems to be successfully integrated into healthcare practices, there’s an urgent call for human-centred design that comprehensively considers clinical settings’ realities, complexities, and nuances.

Conclusion:

The conference was really great, leaving me eager to secure tickets for next year. I wholeheartedly recommend it to academics and practitioners alike, and even more so for those who straddle both worlds as “pracademics.” The event excels in finding a balance between evidence-based insights and practical applications, shedding light on the persistent theory-to-practice gap that demands our attention.

One resounding lesson was the importance of meaningful research in crafting experiences that truly resonate with our audience. The BAD Conference gathers an array of experts from psychology, anthropology, philosophy, and beyond to dissect the behaviour science skills essential for UX design. It’s a great opportunity to delve into crucial frameworks and research methods, unlocking the secrets to understanding users on a deeper level, tapping into their needs, and deciphering their perspectives.

Moreover, these events are not just about learning—they’re about connecting with a community of individuals driven by the same passion, all eager to explore the latest industry developments. The networking opportunities offer a chance to engage with like-minded individuals keen on staying at the forefront of the ever-evolving field of Design .

Leave a Reply