By John Maiden

On 18 January 2024, the Open University and the project Religious Toleration and Peace (RETOPEA), was mentioned as an “exciting” teaching innovation during a Lords Grand Committee on Religious Education in schools. The project was described as presenting young people with an opportunity to “think outside the box about their own experiences of religious diversity, tolerance and intolerance”. The following week, the OU team was able to follow up on this with an education policy briefing event in Westminster. Here we presented some of the outcomes and potentialities of the project, and particularly our ‘Docutubes’ methodology. This is an approach through which young people have been encouraged to learn creatively about religious diversity in past, present and their own experiences, by writing, making and editing their own short films.

The Docutubes approach was first developed as part of a Horizon 2020 funded project in collaboration with various universities and partners across Europe. Since this has ended, further support from the Culham St Gabriel Trust and the OU’s Open Societal Challenges programme, has enabled the OU team to test the methodology in a number of new contexts, including the Muslim-majority countries of Albania and Jordan, in a wider range of English schools, and in both a Protestant and Catholic school in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

In the first half of the policy event, members of the project team, John Maiden, Stefanie Sinclair and John Wolffe, along with Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse, a RETOPEA colleague from KU Leuven, explained the Docutubes approach. We spoke about how engaging young people with an accessible online archive of primary sources – ‘thinking like historians’ – and then the creative learning approach of Docutubes, had demonstrated the potential to address common ‘presentist’ understandings of the religious diversity. Specifically, the approach is able to challenge the widely held views about the past which associate religion with conflict. We then heard from two educators, Richard Brown (Head Teacher, Urswick School, London) and Ruairi Geehan (Mercy College, Belfast) about their experiences of RETOPEA, as well as Dr Renee Hattar, Director of the Jordanian Royal Institute of Interfaith Studies, which hosted a Doctubes workshop in 2023. Finally, a young people who had experienced a Docutubes workshop described his own positive experiences of the project, working alongside young people from other religious traditions, in the context of an interfaith youth camp organised by the Rose Castle Foundation.

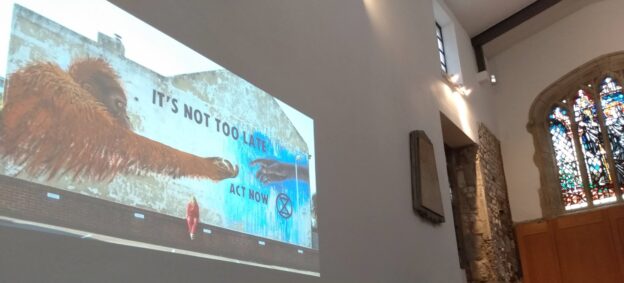

In the second half (pictured), we heard responses from expert practitioners in the fields of teaching, peace-making and interfaith: Helen Snelson (Teacher Education, University of York, Chair of the Historical Association’s Secondary Committee and a EuroClio Ambassador); Rosie Dawson (Freelance religion journalist, documentary maker and radio producer); David Porter (Strategy Consultant for the Archbishop of Canterbury); Riaz Ravat (Contributor to the Commission on Islam in the UK, Prime Minister’s Extremism Task Force and the Commission on Religion & Belief in Public Life). Here, there was enthusiasm for the approach, and particularly how it might provide spaces for young people to talk with each other about potentially difficult or controversial issues in constructive ways. There were also challenges. How can we help ‘time poor’ teachers, for example of History and RE, to incorporate Docutubes into their curriculum? Given that negative views about religious diversity often begin in the home, are there ways in which Docutubes could equip teachers and young people to challenge stereotypes and generalisations which might learned from parents and family?

The OU team (including Katelin Teller) plan to continue to develop and expand the use of the Docutubes methodology, and this event enabled us both to raise awareness and see new potentialities. We are grateful to all the participants for their contributions.

Watch this space! And in the meantime, for more information on the Docutubes approach, see this OU Badged Open Course.