By Hugh Beattie

Is war the new normal in the Middle East, asks a recent Daily Telegraph review of Elliot Ackerman’s Places and Names, about American involvement there since the turn of the century.

As far as Afghanistan is concerned, the answer must be yes. For much of the 20th century the country was relatively peaceful. Forty-one years ago (in April 1978) a left-wing government took power in the country in a military coup, and attempted to introduce a series of major social and economic reforms, provoking a major insurgency. At the end of 1979 Soviet troops entered Afghanistan to defend the new government. The country has suffered ever since from an ongoing civil war which has varied in intensity, but has never really ended.

As we approach the 40th anniversary of the Soviet invasion, it may be a good moment to reflect on why conflict has continued for so long. A few brief thoughts.

Firstly, there are some agriculturally very productive areas in different parts of Afghanistan, but there is a desert area in the south, and mountains (rising to 7,492 metres in the east) run across the country from east to west. These help to make communications difficult and have contributed to a strong sense of regional and even local rather than national identity.

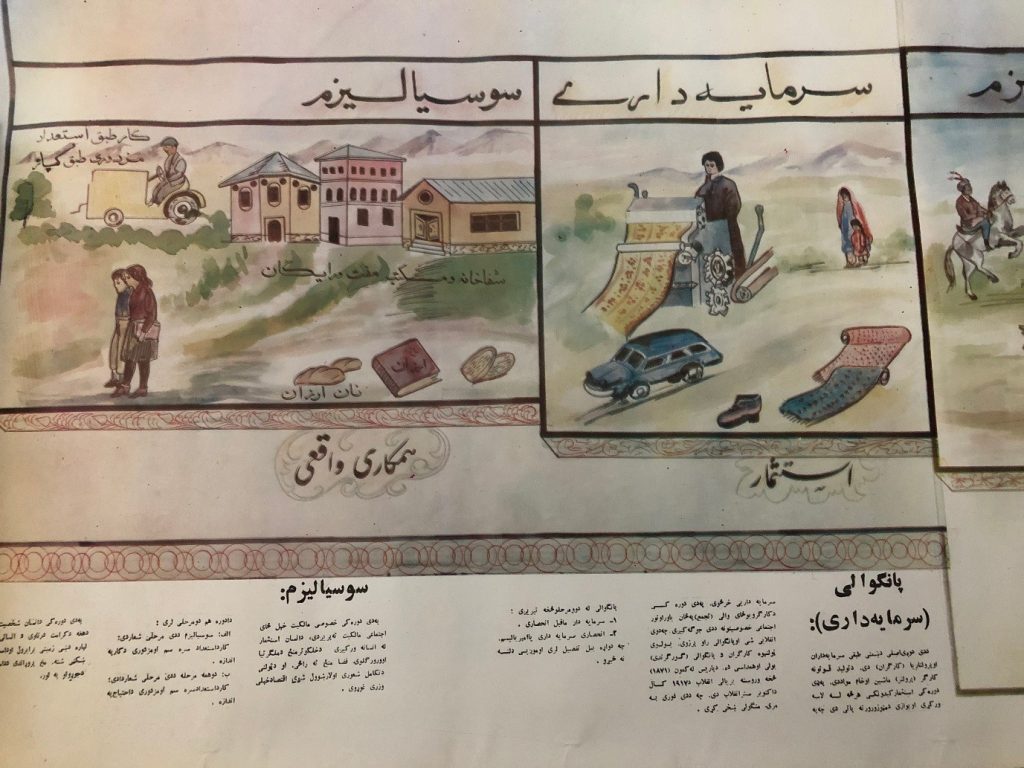

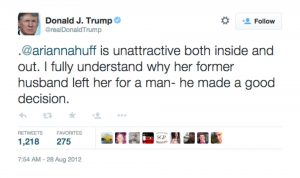

Part of a propaganda poster produced by the new government in 1978. It depicts the last two stages in the evolution of human society according to Marxist theory; it reads from right to left – the image on the right represents capitalist society and the one on the left the final stage – the socialist utopia.

Secondly, the Afghan state, largely a product of later 19th century British imperialism, has shallow roots. Even in the later 20th century, its reach was often quite limited in rural areas and local communities maintained a considerable degree of independence.

Thirdly, there is the country’s ethnic diversity. About half the population identify as Pashtuns and Pashtu is often their first language; there are substantial minorities, who have different mother-tongues, including Persian, Uzbeki and Baluchi.

Fourthly, there is the presence of a number of powerful neighbours and near neighbours, including China, Pakistan, India and Iran, each interested in maintaining as much influence over the country as possible, and keeping others out. This is partly for strategic reasons, and partly in the hope of gaining control of the country’s mineral wealth. So, for example, since the early 1990s Pakistan has usually supported the Taliban, while its neighbour and rival, India, has tended to support more secular movements. Other, more distant, actors have also interfered during the last half-century, ranging from the USA and the UK to Saudi Arabia and the UAE (as well as Al-Qaida), NATO and the UN.

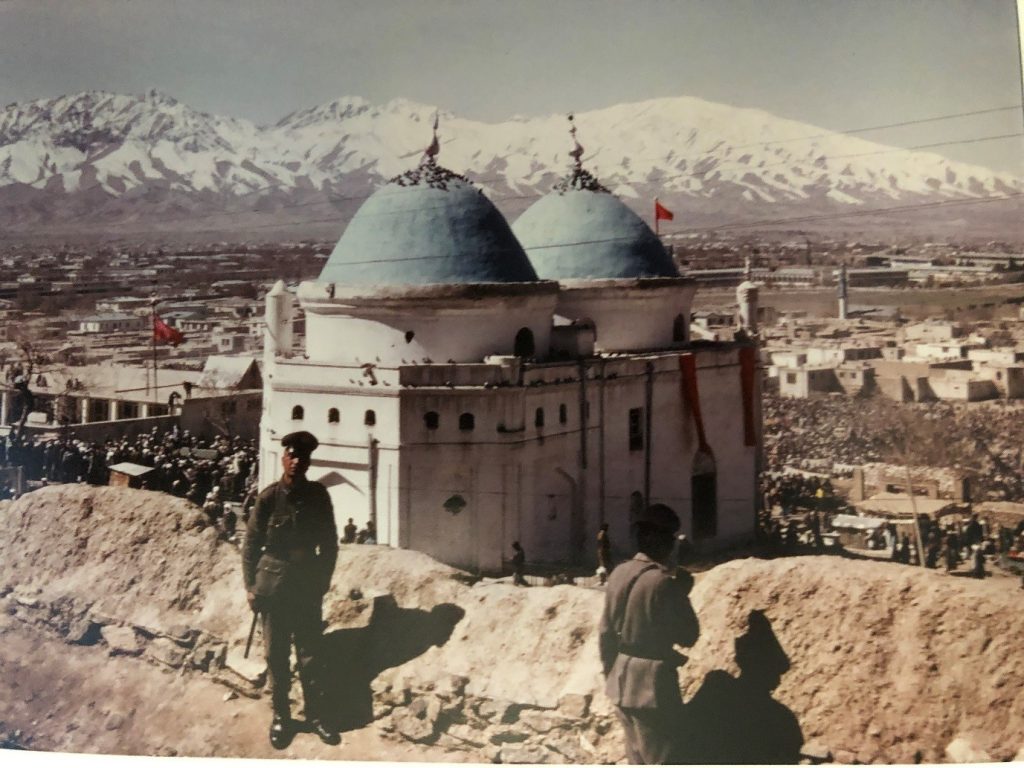

A shrine in the Kabul suburbs, the Ziarat-i-Sakhi, which has Imami Shi’a connections, taken on New Year’s Day (according to the local calendar March 21) 1979.

The religious factor is an important one too, with the almost all Afghans being Muslims, and influential religious leaders having a history of mobilising resistance to foreign intrusion, for example the Mullah Din Muhammad, known as Mushk-i-Alam (meaning ‘the perfume of the world’), who helped to lead resistance to the British during the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-80).

As a result, during the 20th century Afghan governments usually had to tread carefully and not interfere too much with society and the economy if they wanted to stay in power. Some rulers tried to compensate for their weakness by looking for help from outside, but accepting aid from one foreign country in particular, especially a non-Muslim one, was usually very unpopular. It also encouraged other states to intervene, in order to prevent a rival getting the upper hand there.

After the overthrow of the Taliban government in 2001 following 9/11, it seemed possible that a new page in Afghanistan’s history might be turned and a new socio-political order based on freedom and democracy might emerge. But the problems were enormous, and all too soon the ‘golden moment’ passed. Soviet troops had left the country in 1989 leaving behind a weak government in Kabul and a number of powerful leaders (often referred to as warlords) in the provinces. Now it seems that in its turn the USA will soon withdraw almost all its troops, leaving a weak government in Kabul and a renascent Taliban in control of at least half the country. Sad to say, peace seems as remote a prospect as at any point since 1979.

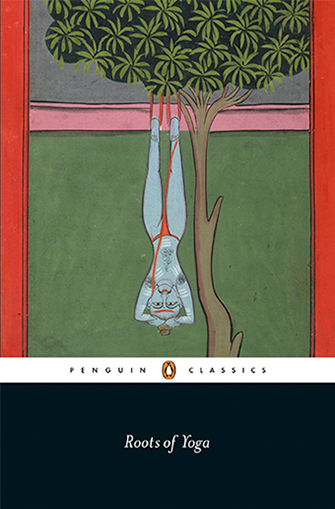

Roots of Yoga, authored by James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, is the first major text from

Roots of Yoga, authored by James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, is the first major text from