This week’s second reading of the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill moves the UK one step closer to a significant aggravation of the relationship with the EU.

With no Tories voting against the Bill – partly because it was presented as a technical exercise – the government is pushing on with a faster committee stage.

However, as discussed last week, the effects of the Bill are anything but technical, eviscerating almost all the substantive provisions of the Protocol – even those nominally protected.

One point that wasn’t addressed in that post was the use of the doctrine of necessity as a justification for the Bill.

In essence, the doctrine is a common law concept that sometimes one is forced to break one’s commitments because that’s the only way to deal with a serious problem. Unlike force majeur, where a state is involuntarily put in a Bad Situation, necessity is a voluntary action.

It’s not much used, mainly because states are pretty careful about signing up to stuff and because the other exit routes – coercion, error, etc. – usually cover it. The only case you might have hear of where it was used was the bombing of the Torrey Canyon after it ran aground in 1967. You’re not supposed to bomb ships [I know], but the action prevented further pollution, and no-one really complained.

As a result, the doctrine is not fully formed in international law.

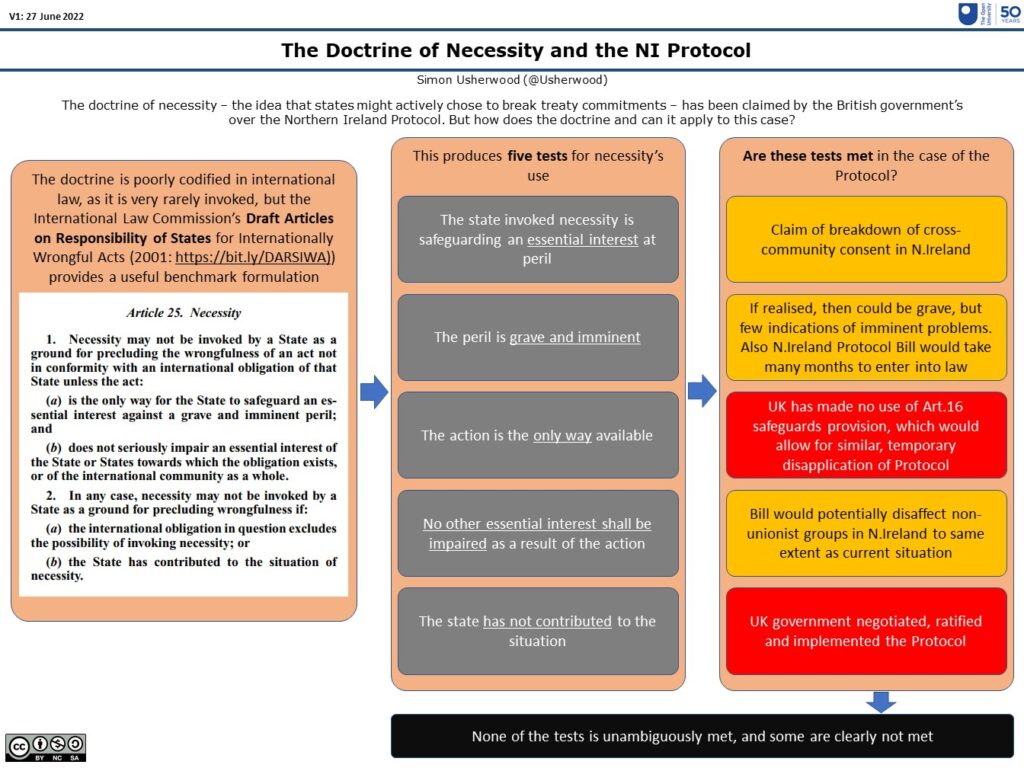

The main reference point has been the International Law Commission’s Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, drawn up in 2001. While still draft, there are as close as we get to a benchmark.

The graphic sets out that benchmark, and the key tests that apply, plus whether they are met in the current situation.

As you’ll see, none of the tests are clearly – or even, much – met in the government’s explanatory notes for the Bill.

Moreover, two of the tests are definitely not met. The failure to use Article 16 of the Protocol – despite the government’s extensive discussion of how it would be justified in using it – is only surpassed by the government’s fundamental part in creating the current situation through its negotiation, ratification and implementation of the Protocol in the first place.

Thus, even if one accepts the framing of the threat to cross-community peace and stability as grave and imminent, that still does not allow for use of necessity as a justification for a Bill that not only breaks international commitments, but also very likely creates just the same threat to cross-community peace and stability, albeit by the removal of the Protocol.

This much will have been evident to all involved in Whitehall and Westminster beforehand. Liz Truss’ comments during Monday’s debate highlight that the Bill is much more about trying to push EU member states to reopen the Commission’s mandate than it is about following through on the Bill’s provisions: we might also add in a dose of leadership ambition here too.

But with no sign that the EU is going to move, it is hard to see how the government doesn’t paint itself into even more of a corner on this. With Johnson talking up the need to support Ukraine in defence of a ‘rules-based international system’, it seems especially counter-productive to be playing fast and loose with those rules.