The title of this post feels insanely optimistic, given the events of the past weeks, but if we don’t try then we certainly won’t succeed.

Last month I submitted some evidence to the Follow-up inquiry on the impact of the Protocol, run by the Lord’s EU Committee’s sub-Committee on the Protocol. Being very aware of my limits, I only wrote about the dynamics of EU-UK interactions on the issue and how a possible restarting of constructive relations might look.

My unwritten conclusion was that the current UK government was really unlikely to make this work, or would even try to make it work, since its first step was to engage wholeheartedly with the current Protocol system, to show it was making best efforts. Only once that path is exhausted (and seen to be exhausted) would the UK get renegotiation on the table.

Of course, this has been overtaken by the publication last week of the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill.

Resting on a very dubious legal basis of a doctrine of necessity, the government argues that the Protocol’s effects are so terrible as to require urgent action, albeit through passing legislation that may need months to come into effect and while also arguing it is just ‘minor bureaucratic changes‘.

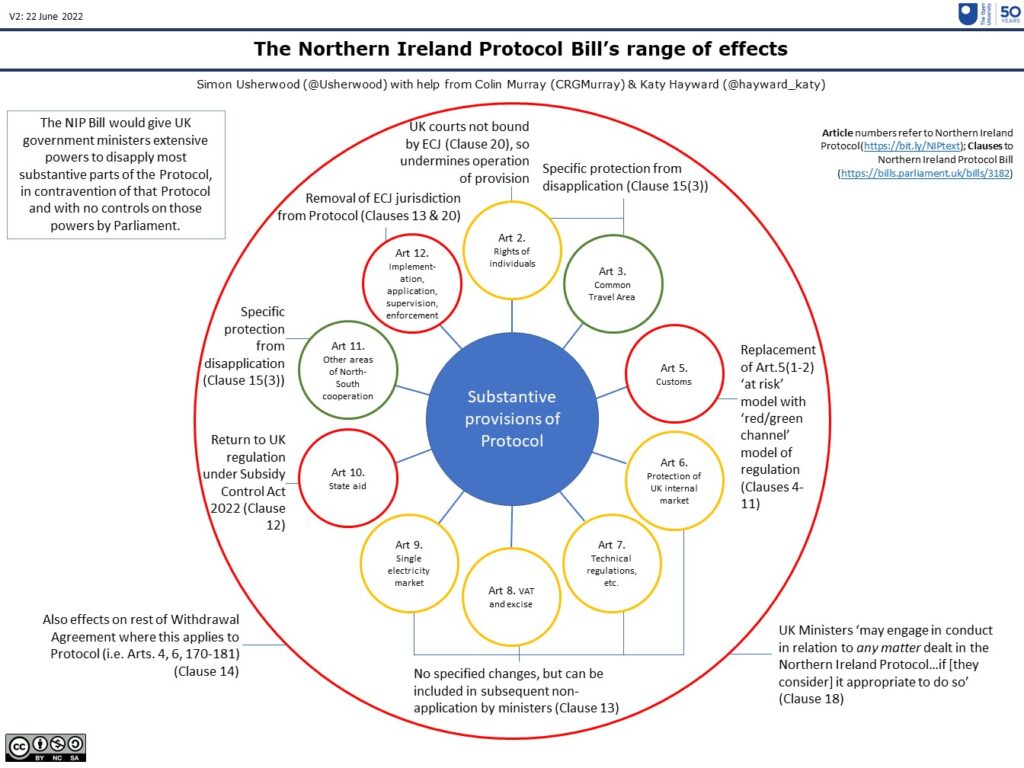

Even if we disregard the justification, then we can still say that the Bill proposes a fundamental reworking of the Protocol, as laid out in the graphic below.

Even those (few) parts of the Protocol that appear to be protected from changes – notably Art.2 rights for individuals – are compromised immediately by the removal of the ECJ from any UK-based legal judgements (so people can’t access definitive ECJ rulings on relevant provisions) and have the shadow of Clause 18 powers hanging over them.

Clause 18 would allow UK ministers to take whatever they like on any aspect of the Protocol as they see fit, without Parliamentary control. To call this sweeping would be an understatement and sets up a much more antagonistic passage through the Lords (and probably with some Tory backbenchers).

As a whole, the Bill reads like a legal embodiment of 1980s Millwall supporters.

Legally, the Bill stands on the weakest of justifications, just as the chances of it forcing the EU to the negotiation table like vanishingly small. Given that both of these things was very evident beforehand, the key question is ‘why carry on regardless?’

As I’ve long said, it reflects much more on the state of domestic debate than on real, existing international relations.

For more evidence of this, we might look to yesterday’s publication of the Centre for Brexit Policy’s report on Global Britain.

I only focused on the EU/Europe section in my thread below, but it suffers from the flawed assumption that just because you think the EU is rotten, so must everyone else.

https://twitter.com/Usherwood/status/1539548002267934721?s=20&t=cjEWKYKetW2lp_1scEf_jw

And so we continue to go round the same old problems, again and again.

Even if the NIP Bill gets binned and even if the CBP’s ideas don’t become official policy, the issues still remain about how to find a mutually-acceptable and stable solution for Northern Ireland. Which seems rather lost in this debate.