Since we’re back in a hotter phase of the NIP rhetoric cycle, it’s useful to revisit various points.

None of it’s new and I’ve shared all the content below with you before, but apparently that’s not got through to everyone.

The UK government is seemingly on the verge (again) of producing a bill that would resolve its problems with the Protocol. This time, there’s talk of a dual-track system for checks, which I leave to the trade people to deconstruct.

However, the framing of this current effort is that the primary objective of the government’s push is a negotiated resolution, to address the problematic implementation of the Protocol by the EU. Conor Burn gave evidence on this to Parliament yesterday, helpfully summarising in this thread by Tony Connelly:

6/ He said there was "surprise at the scale of implementation versus the perceived risk…we did not believe the EU would insist on the full panoply of checks on product moving to stay in the NI mktplace to be sold and consumed in NI which poses zero risk to the single market"

— Tony Connelly (@tconnellyRTE) June 8, 2022

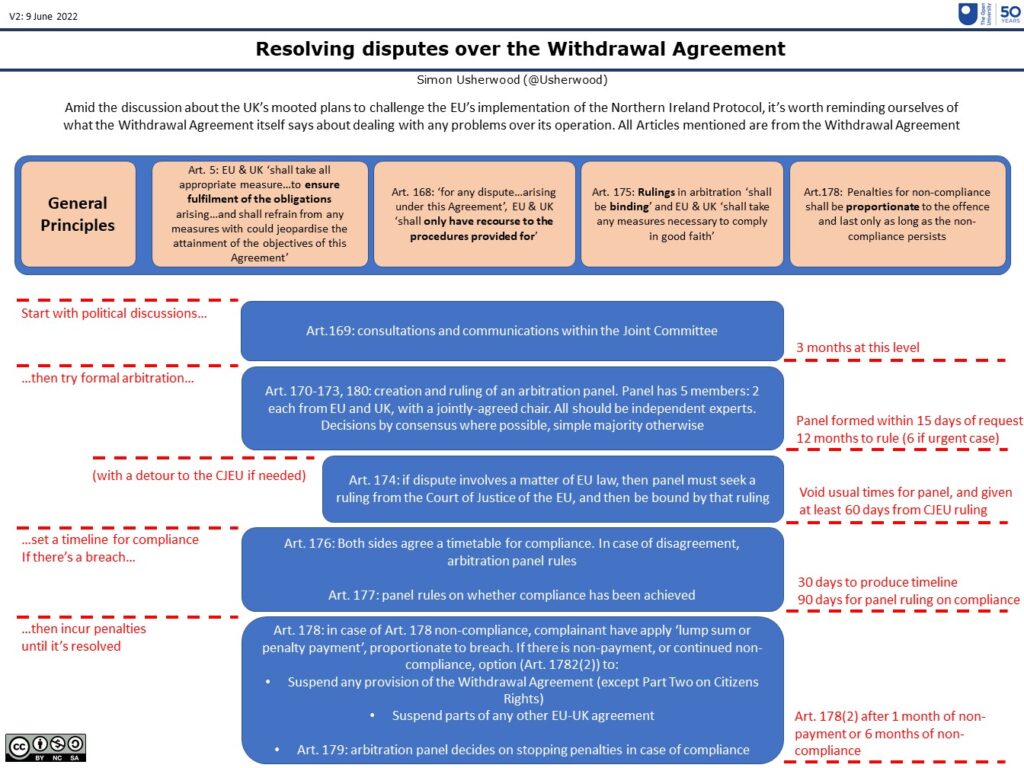

If implementation is the problem, then the Protocol and the Withdrawal Agreement (WA) within which that Protocol sits has a ready-made process: Title III.

Title III deals with dispute settlement, in a graduated and progressive manner, from talks to arbitration to remedies. The graphic below lays out the detail.

This process covers all issues with implementation and (per Art.168) is the only procedure that should be used. That there is no sign of this happening will raise the obvious question about the objectives of the UK government, which makes it less surprising that the EU has trust issues.

We might also note that neither Title III nor Art.16 of the Protocol allows for unilateral domestic legislation to address problems of non-compliance.

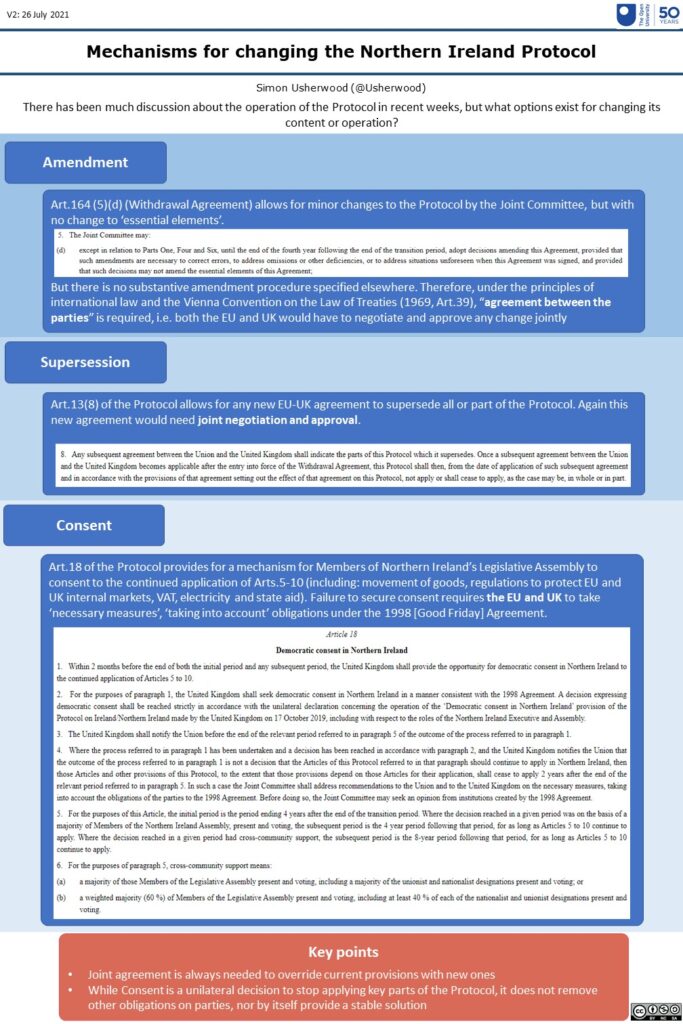

Of course, non-compliance is only one option: the UK government also continues to talk about renegotiating the Protocol.

Again, the mechanisms for changing the text are set out in the Protocol and WA itself, as summarised below:

So change is possible, but only by joint agreement: even the Art.18 NIP consent provision ultimately leaves the parties still having to find a common solution to their various obligations (e.g. Good Friday Agreement, EU law, WTO, etc.), which probably brings them back to something like the Protocol.

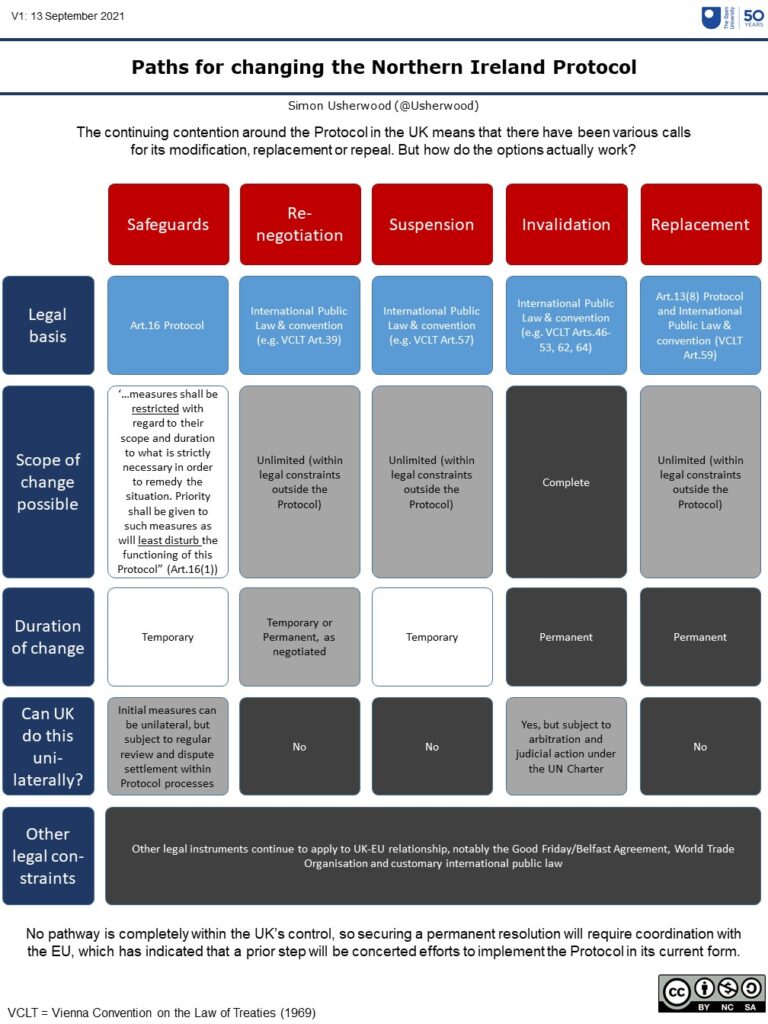

To summarise all this, we can see that options for unilateral action really don’t exist:

Which raises the obvious policy implication that the UK’s best chance of securing change might be to try those joint paths, rather than going off-range with its planned bill. That is almost certainly the advice the government has been given by its advisers. If it does follow through on advancing the bill, then it’s driven by domestic political exigencies rather than the legal or political conditions that materially shape the EU-UK relationship.