This is the first in a series of blog posts that will look back at the history of the Department of Classical Studies at the Open University, on the occasion of the OU’s 50th anniversary.

Lorna Hardwick was a part-time tutor on the very first OU Arts Foundation course in 1971 and was appointed as a Staff Tutor in Arts in the East Anglian Region in 1976. When Classical Studies became a separate department she was its first HoD (‘Head of Department’). She was made Professor of Classical Studies in 2002. Lorna was an author on all the Classical Studies courses as well as on several interdisciplinary ones up until her retirement in 2010 when she was appointed as Professor Emerita. She has supervised many PhD students in the OU and other universities and is the joint series editor of Classical Presences (Oxford University Press). She directed the research project on the Reception of Classical Texts in Drama and Poetry, c.1970-2005, was the founding editor of the Classical Receptions Journal (Oxford) and of the OU online journals Practitioners’ Voices and New Voices. She is currently the Convenor of an international research group Classics And Poetry Now, which works collaboratively to explore the range of relationships between ancient and modern poetry. Here she reflects, not entirely reverently, on some of the key aspects in the history of CS in the OU.

The history of Classical Studies in the Open University has been well documented (Ferguson 1974; Hardwick 2003). There have been highs and lows as well as moments when we might have thought we were in the Theatre of the Absurd. A whole essay could be written about the contributions of students and tutors and the collaborations with the BBC that included the stunning overhead film of Masada (Roman Judaea), the commissioning of Tom Paulin’s play Seize the Fire (a version of Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound) and the extensive material on the archaeology of Troy. However, in my contribution to this 50 Years Blog I’d like to stand back and focus on what is revealed by the social history of Classical Studies and its environment inside and outside the OU.

The founding Dean of the Arts Faculty, John Ferguson was a classicist and insisted that the subject was embedded in early courses (now called modules). The effects, especially when seen from a distance, were paradoxical. Ferguson was a liberal scholar who in many ways was ahead of his time, especially in his determination that classical study should be open to all and that it had a big part to play in dialogue with other subject areas. He had spent time teaching in Nigeria and had a strongly internationalist outlook, insisting that the Arts Faculty’s inaugural first level course (which started in 1971) included a study of Yoruba history and culture. This was widely ridiculed at the time as an eccentric aspiration (and in hindsight its execution might have reinforced polarities between European traditions and those of the exotic ‘Other’), but the insight that students should be made aware of pluralism was sound. Ferguson’s global perspective also sat paradoxically with his view (set out in his Greece and Rome article of 1974) that classical studies was at the root of what he called ‘our western culture’. There has subsequently been extensive work to analyse the forms and implications of such perspectives (see most recently Mac Sweeney et. al., 2019). The limits of liberal humanism were also revealed in the strongly masculine staff profile of the OU at its inception, especially in senior posts. Ferguson’s Greece and Rome article even managed to refer to a female ancient historian in terms of her husband’s career. Those beginnings offer a salutary warning that even the most prescient can be unwitting prisoners of the norms of their own time, which they then transmit to others. Celebrations of progress are best tempered by a critical look at underlying assumptions and that is as true today as it was then.

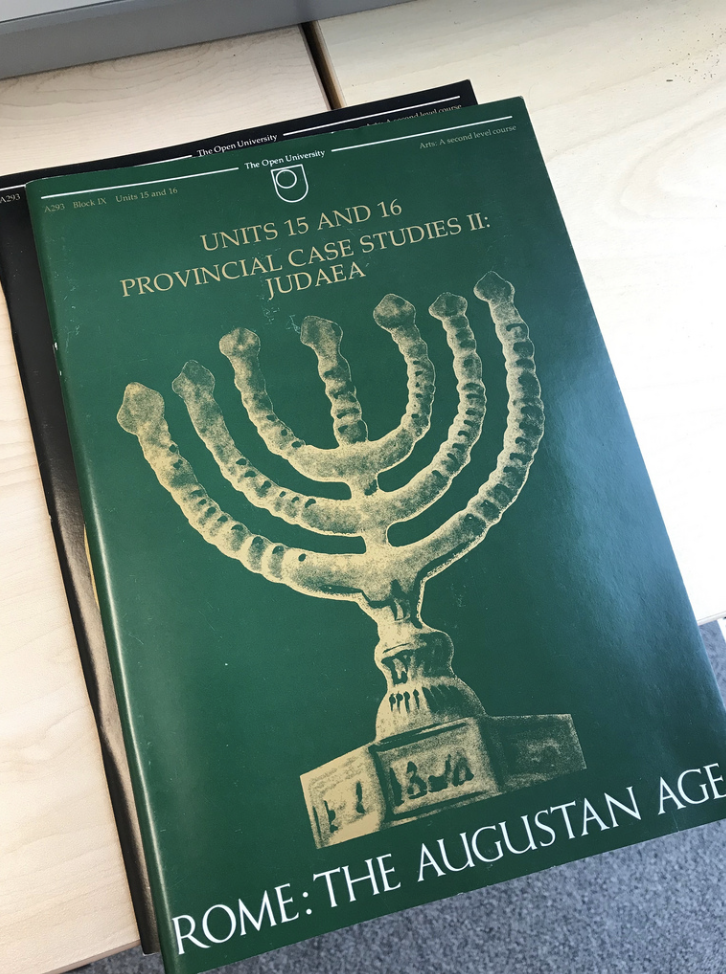

Cover for Units 15-16, case study of Judaea for A293: Rome the Augustan Age (1982-1992). The course included case studies of Provinces in the Roman Empire (including Roman Britain) enabling students to compare and contrast the experience of resistance to Rome and incorporation into the Empire. The seven branched candlestick is a symbol of Jewish religion and cultural identity. It was used by the Romans on their coinage to advertise their victory.

I felt the full force of the unreconstructed gender prejudice of the time when I was interviewed in 1976 for a full time post and the bulk of both the interviews I had was spent quizzing me on why I was prepared to move when I was the mother of a small child and whether this meant that ‘the marriage had broken down’ (sic). Astonishingly, perhaps, I was appointed. My euphoric assumption that this must have been because of my intellectual merit was quickly shattered when I discovered soon afterwards that the decisive factor was that it was considered that I might be able to stand up to a troublesome (non-Classicist) colleague. This was a small example of the power of internal politics to open or close doors and I soon found that this was a big factor in the place of CS in the OU as a whole. When Ferguson left the OU there was a big backlash against CS – its dependence on the Dean’s patronage was perhaps summed up in the metaphor used to describe Ferguson’s relationship with senior management elsewhere in the university; ‘the Barons at the court of King John’. Ferguson’s successor as Dean wanted CS abolished and systematically excluded it from the next two Arts Foundation courses. Much had to be done by stealth, including making sure that CS contributed to the high population interdisciplinary courses.

Aerial shots of the fortress of Masada, the site of Jewish resistance in the revolt against Roman rule 66-74CE. Masada had been built by King Herod in the first century CE on a plateau overlooking the Dead Sea and is now a UNESCO World Heritage site. The Roman siege of Masada and the last stand of the Sicarii defenders was described by the Jewish historian Josephus. The A293 course reviewed the written and archaeological evidence relating to his account.

I also discovered in the early days that class prejudice, even in the OU, mirrored the assumptions of its time. For example, I had to fight a hard battle to prevent the faculty from stipulating, when Ferguson retired, that for the relatively junior appointment that was then permitted the short-list should be confined to candidates who had attended Oxford or Cambridge universities. Many part-time tutors were women and, in the light of this and because they were paid on a ‘piece-work’ basis, they were sometimes disparaged by senior management as ‘pin-money tutors’ (although never by Ferguson, who gave impeccably courteous responses to suggestions and criticism sent in by tutors). Classical Studies at that time was not a separate department but with other smaller disciplines was characterized as a ‘working area group’ (this was the first and, I hope, the last time in my career when I have been a WAG).

Changes in the Classical Studies curriculum over the last 50 years have been partly evolutionary, partly achieved through challenging dominant norms and partly responsive to the broadening of its constituency of students. In the 1970s and 1980s the study of Greek and Roman antiquity was largely thought to include two aspects: study of literary and historiographical texts in the original languages and the study of society in terms of politics and war. Social History, as opposed to military and political history, was frequently marginalised as a ‘soft’ option (what might be called ‘ladies’ history without the hoplites’). Nowadays Social History is central to the subject area nationally and internationally. The early OU Classical Studies courses contributed to that development but trod gently. They did include Social History but as separate sections with revealing headings such as ‘Women’ and ‘Slaves’. This gradualism in acceptance and then mainstreaming of new areas of study is a characteristic of Classics and Ancient History in general, a more recent example being Reception Studies (Brockliss et al., 2012).

Cover of the source book that accompanied the ‘Which was Socrates?’ section of the very first Arts Foundation course, A100 (1971 – 1977). This substantial source book, edited by John Ferguson contained translations of virtually all the ancient sources that referred to Socrates and students were taught how to evaluate and compare these.

Also marginalised in the subject community as a whole (and associated with both gender and class assumptions) was the reading of ancient texts through translations. The attitude of OU course approval committees, both in the Faculty and in the wider university, to the introduction of classical language teaching was a bizarre mixture of incredulity and patronizing contempt for mature students. It was argued that OU students wouldn’t want to learn the languages as these were irrelevant and elitist (note the conjunction) and, even if they did so wish, OU students would not be intellectually capable (at their age and with their lack of access to classical languages at school……). That hot-potch of prejudices was then deployed to argue that since the OU taught CS through translation the discipline would not have the respect of other universities and so should wither away. The outcome of much determination and support from the more enlightened Deans of the 1990s was that after a few years the OU was teaching Greek to more students than the rest of the UK universities put together. However, attitudes in the wider community to adult and life-long learning could still be ignorant and dismissive. One Minister for Higher Education commented when he addressed the Council of University Classical Departments that ‘all adult education is merely remedial’ and that it should therefore be of no interest to universities. He got a rough ride from the CUCD, which I found encouraging.

Gaining the respect of other universities was important for CS in the OU in the 1980s and into the 90s. There were positive sides to this – for example, distinguished classicists and ancient historians agreed to be examiners and course assessors. We and our students benefited enormously from this (although my plagiarism from Swallows and Amazons that ‘if duffers better drowned and if not duffers won’t drown’ was not universally appreciated). Nevertheless, approval from the classics community did not always bring rewards from the OU. When we gained a maximum score in the Teaching Quality Assessment in 2001, the response of the OU leadership was to cancel an additional post that we had already been allocated, on the basis that we clearly didn’t need any additional staff! It was unfortunate that national teaching assessments did not bring with them any resources – in contrast to research assessment, which (as I found when I was a member of an assessment panel) actually rewarded successful departments.

John Ferguson with masked actor. Aristophanes’ comedy The Clouds was one of the sources read by students for their study of Socrates. A BBC TV programme dramatized extracts from the play, including the scene in which Socrates is suspended from a basket. The programme was shown on TV in the early evening and provoked protests from general viewers who objected to the scatalogical language of Aristophanes’ play. Some even wrote to the national press to complain that OU students were getting their degrees by sitting in their armchairs watching obscene drama on TV.

Emphasis on gaining the approval of our colleagues elsewhere in the HE system had its drawbacks as well as its advantages. I think we were too slow, and perhaps too timid, to push ahead with a fully integrated pedagogy of language learning and translation. This can work effectively in both directions by including ‘language awareness’ strands in courses taught through translation and by teaching students how to compare different translations of key passages. I wish now that we had grasped the nettle earlier and challenged the entrenched belief (which still persists in some quarters) that reading through translation was essentially inferior, rather than different. Reading through translation is now an accepted strand in CS in all universities, although it is not systematically taught everywhere. Eventually, OU second level modules did explore this but we should have done it sooner. We could have used our courses more adventurously to transform perceptions by enabling students, and tutors, to experience how translation and text can inform one another. This is just one example of how research and pedagogy can work together. Translation Studies research has brought forward new models of how source languages, epistemology and translation interact. The nexus between classical languages and translation has played a significant part in this (Bassnett 2014).

The other area in which I wish we could have made swifter progress is in helping our students to explore and understand how study of antiquity is not the preserve of any one cultural tradition. The cultures of antiquity are pre-Christian (to a large extent) and pre-Islamic but are transmitted by and important for both traditions. They provide not only critical distance from the present but also a field where different perspectives and world-views can be studied in a non-polarized way. The OU course Homer: Poetry and Society included a ground-breaking section that compared performance of story-telling in Indian and Homeric oral poetry. The performance of Greek plays around the world has provided excellent primary material that has been included in OU courses at Honours and Masters level (Mee and Foley, 2011). Taking Classics out of its nervously ‘niche’ closet and re-engaging with the study of cultures and their interactions provides a substantial challenge but also an opportunity for developing the lines of enquiry and working methods that are imperative in the modern world. After all, the plural and diverse threads in ‘European culture’ are rapidly transforming it and there are radical questions to be asked about the extent to which classically derived traditions have been at worst instrumental and at best complicit in racialising and marginalising others.

I realise that emphasising the substantial potential of Classics for deepening critical analysis and comparison does run the risk of collapsing into a claim of ‘exceptionalism’, an approach associated with the imposition of special authority. So I prefer to use the word ‘distinctive’. There are indeed distinctive ways in which the study of Greek and Roman antiquity and its reception can not only ensure that future generations get to experience these exciting texts and material culture, it can also provide critical comparisons for other times, places and languages right up to the present. It has become a mantra to say that the ancient texts are ‘good to think with’. I think this is true, provided that we do not suppress the darker sides. They also make us think! Given the current public debates about suppressing or erasing the unacceptable aspects of the relatively recent past and its texts and monuments, the study of antiquity and of how its various aspects have been eulogised and repressed provides a critical field for addressing contentious questions, without either sanitizing or demonising the past.

Looking ahead to the next few years of teaching and research in CS, I can see that the study of ancient religion and its material and social manifestations would be a growth area. There is also a pressing need to analyse more critically the history of scholarship and to explore how, throughout the history of the subject, the often unexamined assumptions and norms of the most influential scholars have shaped not only the interpretations of the texts but also the values that have accreted around them and which have seeped across disciplines and into society at large. Perhaps as it embarks on the next 50 years, CS in the OU can push that agenda too?

Opening scene from Seize the Fire, an adaptation by Tom Paulin of the fifth-century BCE tragedy Prometheus Bound, attributed to Aeschylus. John Franklyn-Robbins is shown as Prometheus, chained to a rock (set design by George Wisner). In the myth, Prometheus had offended the gods who retaliated by chaining him to a rock where an eagle pecked out his liver, which regenerated overnight so that the torture could continue the next day. The adaptation was commissioned by the BBC for the course A209 Fifth-century Athens: Democracy and City State (1995-2005). The staging was directed by Tony Coe (BBC producer for the course). Published text: Tom Paulin, 1989, Seize the Fire, London: Faber and Faber. The production is documented on the database of productions of Greek drama, www.open.ac.uk//arts/research/greekplays/drama (data base number 217)

The gods’ messenger Hermes visits the chained Prometheus. Stephen Earle played Hermes as a spiv, dressed in leather jacket. His role was to try to persuade Prometheus to compromise with the gods and secure his release.

Io is shown visiting Prometheus and telling the story of her torment by Zeus who sent gadflies to pursue her round the world. Played by Julia Hills, Io was costumed as a Marilyn Monroe look-alike. Ancillary material to the course included a video clip of Marilyn Monroe singing ‘Happy Birthday Mr President’ at a birthday party held for President John F Kennedy.

References:

Bassnett, S., 2014, Translation, London and New York: Routledge.

Brockliss, W., Chauduri, P., Lushkov, A.H. and Wasdin, K., eds., 2012, Reception and the Classics: An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Classical Tradition,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ferguson, J., 1974, ‘Classics in the Open University’, Greece and Rome, 21.1 (April), 1-10.

Hardwick, L, 2003, ‘For ‘Anyone who wishes’: classical studies in the Open University, 1971-2002’, in J. Morwood, ed., The Teaching of Classics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 149-158.

Mac Sweeney, N., et al, 2019, ‘Claiming the Classical: the Greco-Roman World in Contemporary Political Discourse’, CUCD Bulletin 48, https://cucd.blogs.sas.ac.uk/bulletin)

Mee, E. and Foley, H.P., eds., 2011, Antigone on the Contemporary World Stage, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

The Womens Classical Committee campaigns and organises workshops on all aspects of gender and equality in teaching, research and university employment practices.