There is (rightly) no getting away from discussion of the climate emergency, especially this week as Cop26 is underway in Glasgow. Whilst many problems that contribute to the crisis are global, political and very difficult to solve, there are others that, frustratingly, are driven by greed, social media, and personal choices. We could put the brakes on so easily, but instead, we keep stoking the fires. The pandemic, to a greater or lesser extent, forced us all to re-evaluate how we live. With shops and social venues shut, there was less opportunity, or need, to buy new clothes or other products to impress, or to keep up with the Joneses, as apart from the odd sighting on zoom or social media, we didn’t really know or care, (at least at first), what the Joneses were wearing or doing. In fact, if we did see anyone buying or doing too much, there was a tendency to judge.

Locked down at home, for many there was the realisation that we simply had too much stuff and rather than accumulating more, we saw a mass decluttering. People started to find their own entertainment, reconnected with nature, baked bread, and kept a weather eye on the neighbours rather than checking out their latest extension or the size of their amazon delivery. Lockdown provided an opportunity. The reset button had been pressed. Or had it?

The way we are persuaded to consume has changed radically in my lifetime. Training as a designer in the 80s, understanding the mechanics of persuasion and the power of branding was exciting. Although using manipulative techniques, advertising was driven and approved by the companies selling the goods, and vetted by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA). Today, with Millennials (born 1981-1996) and Generation Z (born 1997-2012) no longer watching terrestrial television channels or reading printed magazines as they used to, products are increasingly advertised by the consumers themselves, with people buying (or being given) products to show, review, sell on or send back, creating a largely unregulated swamp of ‘content’, and I use that word guardedly, despite the ASA’s new regulations for the medium. This new generation of entrepreneurs have transformed their chosen social media platforms, growing their audiences with an ease that now adds a serious threat to the planet.

Instagram was originally just a platform to share photos but it quickly moved to a place where people sought affirmation and ultimately status. It was the home of beautiful people, beautifully styled in beautiful places, sometimes with no foibles about following the hoards to trample, litter and risk damaging nature’s spectacular places (and even themselves) just to get that same ‘trophy’ shot. The post on the grid became more important than the actual experience.

So easy to use; so easy to exploit. With reality carefully staged, the selfie became a shop front. Similarly with YouTube; the early ‘unboxers’ evolved into polished tech reviewers and prolific ‘haul’ vloggers, all constantly posting to maintain their following. Somewhere along the line, it morphed into a job. When 20-year-old Molly-Mae Hague was asked what she ‘did’ as she entered the Love Island villa in 2109, her answer was, “I do Instagram’.

Although for Baby Boomers and Generation X the idea of a career whose main aim is getting 1M followers on a social media account can seem rather vacuous, it’s not hard to see its attraction. A large following can bring phenomenal wealth that grows even as the fortune hunters sleep. High earning influencers can get thousands of pounds for each Instagram post, and there are further rewards for every viewer’s click on their YouTube or TikTok posts and for every purchase via their affiliate links. There are even online calculators to see how much you can earn for each post you make.

Despite seeming ephemeral, this kind of digital success can lead to more tangible careers. That same Molly-Mae caused a furore on Twitter early this autumn when she shared the ‘well done to myself’ treat she had bought after being made creative director of fast fashion company PrettyLittleThing. The ‘treat’ was a £37,400 Cartier bracelet. Such conspicuous consumption, (the accompanying photo also showed an equally expensive Rolex giving rise to comments that she was effectively wearing a ‘house’ on her wrist), not only angered people struggling financially through the pandemic, but also those creatives who had formally trained in the industry, and worked hard through the ranks and yet still found it a challenge to secure such a role. The publicity prompted further scrutiny of the problems with fast fashion. A similar company, ‘Missguided’, had earlier misfired with its four part C4 documentary, ‘Inside Missguided’, which iNews described as a ‘PR disaster’. Despite aiming to show that the company was run by, and empowered, women, in reality there was a huge gender paygap, and issues in the manufacture of the products were not explored; issues common to a number of the major fast fashion companies. Missguided’s website boasts “Its [sic] not just fast fashion – its [sic] rapid fashion. We drop up to 1000 brand new styles every week, working constantly to bring our babes the freshest pieces”. When its founder, Nitin Passi, was questioned about the environmental impact of its practices, his response was, “If we don’t do it, someone else is going to do it.” Unfortunately, he isn’t wrong.

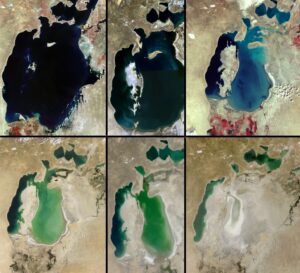

Fashion has never been so affordable as it is today, and the means of promoting it, never so attractive and easy, and yet the price we will pay for it, which will particularly, ironically, affect those who are driving it, will be catastrophic if we don’t act now. In her 2018 documentary, Fashion’s Dirty Secrets, Stacey Dooley exposed the environmental impact of fast fashion, exploding the myth that natural fibres are more ecologically friendly. The disappearance of the Aral sea due to its water being diverted to Uzbekistan’s cotton fields, shocked viewers – the impact on the local communities has been devastating. Seeing that against the profusion of products sold by companies the influencers promote is very troubling, and yet changing behaviours will be difficult. You can see why a favourite influencer could be ‘useful’ in curating the products for a customer. The Chinese online store, Shein, for example, currently has a mind-boggling 91,092 different dresses, 98,176 tops and 10,692 trousers on offer! With such a plethora of styles, fashion ‘design’ as we knew it, hardly figures. Customers just lap up the cheap prices, and knowing that they can become affiliates, with any sales made through their promotional videos or Instagram bagging them up to 20% commission, the lure is even stronger. In the past twenty years there’s been a 400% increase in the amount of clothing we consume. On YouTube there are thousands of ‘haul’ videos of mainly young women and teenagers unpacking copious carriers from their online or in-store spends, mock-joking about how they accidentally spent £XXXs, eliciting likes, comments and further click-purchases from their adoring fans, thanking them for their hard work and telling them how wonderful they all are. Many of them are haulers themselves, thus continuing a never-ending cycle of mutual appreciation and financial benefit that’s disastrous to the planet.

The nature of haul and tech reviewing videos and Instagram posts means that the influencers have way more products than they would ever be able to, or want to use. Many hauls run on the theme of ‘should or shouldn’t I?’, with the presenters asking the audience whether to keep or return each item. If tech reviewers buy every new iteration of a product and compare them to every iteration of the equivalent in a competitor’s brand, they too need to sell on or return their booty, meanwhile recycling more cash into their affiliate’s moneybox. It would be nice to think that the products returned, including all those ‘just in case’ items in a different size, in our possession for just a matter of hours and still in perfect condition, would be sold on. But sadly no. The item is no longer ‘new’ and companies find it harder to check and repackage something than to send it to the tip. Considering around half of online clothing purchases are returned, that is a hell of a lot of landfill as well as all the attendant packaging and transport costs. Increased online consumption during the pandemic has only added to this and shamefully Britain is the worst offender in Europe buying more than two tonnes of clothing each minute.

Some returns go to liquidation warehouses, and fortunately there are sustainable reverse logistics companies working to create a business model that helps offset the fact that people are never going to stop buying things, but there is still an immense proportion of perfectly good products being made, transported round the world, and then simply deposited in our earth to pollute the planet without ever having had a day of useful life.

Changing what has become a lifestyle consumer model will be extremely hard. In his excellent book, The Day the World Stops Shopping, Canadian journalist J B MacKinnon explores what might happen if our consumption was radically reduced. For all the benefits he shows this could bring, he acknowledges that people will still want to buy, not least for social reasons, within which social media plays a part. Although the impact on the planet is clear, and also, sadly, that some users of social media are plagued with insecurities through daily comparisons to the filtered, curated, over-styled standards of the influencers’ feeds, the latter appear to be suffering from affluenza, focused on wealth, completely oblivious to the repercussions of their actions, and with no desire for a cure, because as yet, it hasn’t negatively affected them.

So is that cheap T-shirt such a bargain? It actually costs the earth.

References:

Advertising Standards Authority. An influencer’s guide to making clear that ads are ads 3af39c72-76e1-4a59-b2b47e81a034cd1d.pdf (asa.org.uk) [Accessed 01/11/21]

MacKinnon, J.B. (2021) The Day the World Stops Shopping: How ending consumerism gives us a better life and a greener world. New York, Vintage.

Wæhler, T. and Dietrichs, E. The vanishing Aral Sea: health consequences of an environmental disaster. The vanishing Aral Sea: health consequences of an environmental disaster | Tidsskrift for Den norske legeforening (tidsskriftet.no) [Accessed 01/11/21]

Leave a Reply