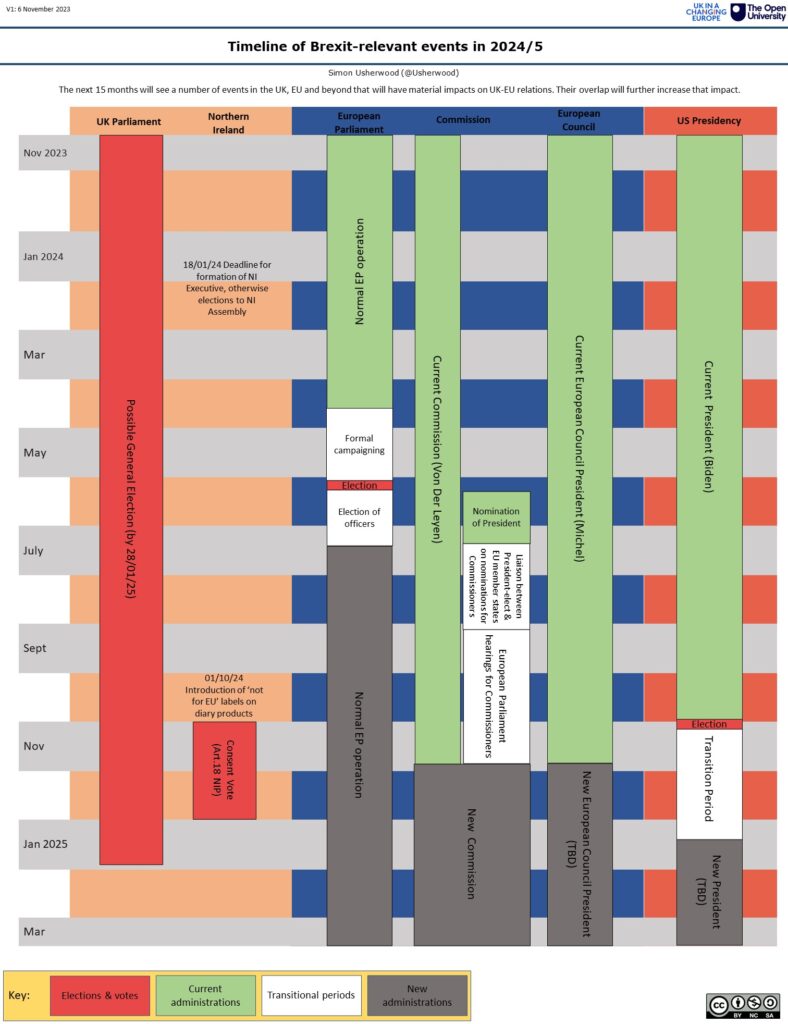

2024 is going to be a busy year for UK-EU relations.

As much as we talk about the 2026 TCA review as a key point, next year will see a full refresh of EU leadership and the European Parliament, plus a probable British general election, plus whatever fallout from a US presidential election might occur.

And more than that, there’s also the Northern Ireland consent process, which will unroll at the end of the year.

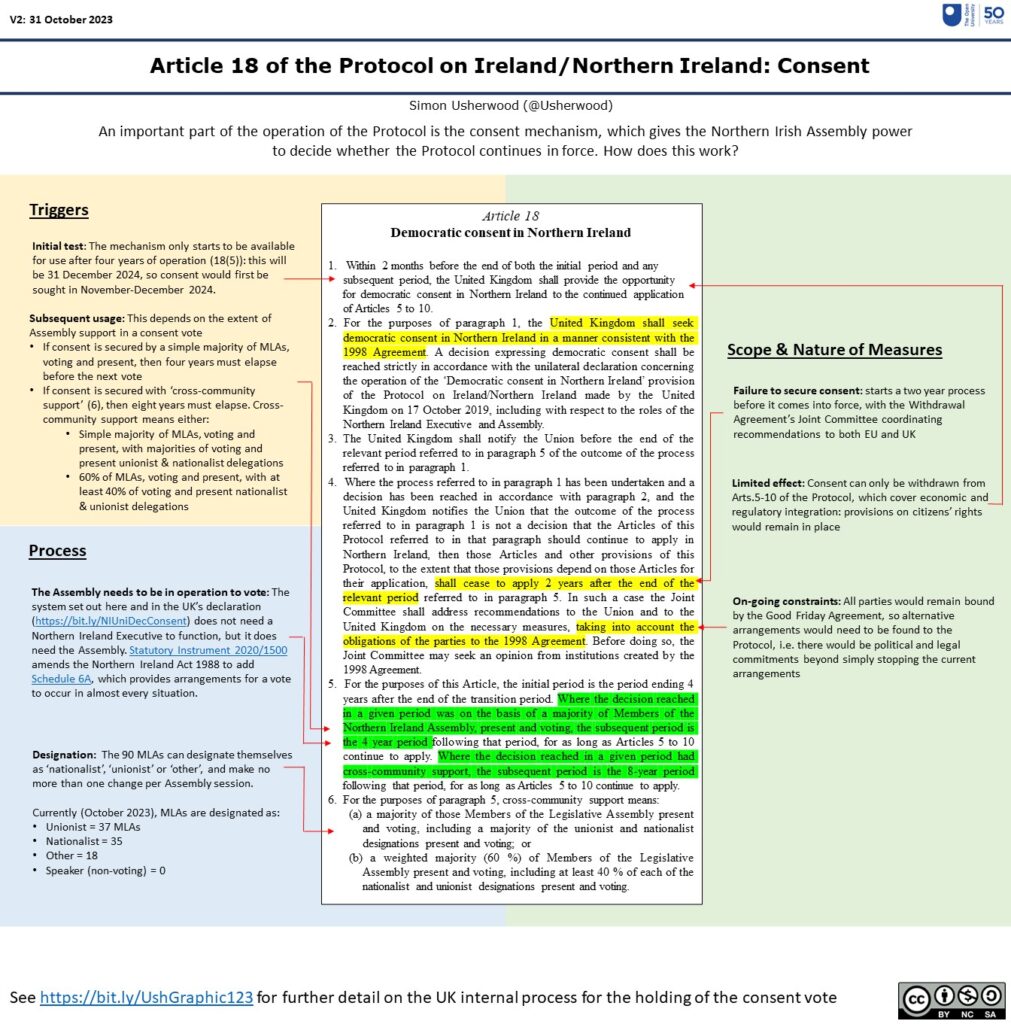

Consent was introduced into the Northern Ireland Protocol as part of Johnson’s shift from back- to frontstop in 2019: while the Protocol arrangements might become the standing system, the NI Assembly would gain the opportunity to express their opinion on those arrangements.

This idea – an extension of the principle of consent so central to the Belfast/Good Friday agreement – is exceptional in giving the power to a sub-national body to determine whether an international treaty continues to apply, regardless of the wishes of the contracting parties.

When we looked at this at the point of negotiation, there was less clarity about whether it meant anything, largely because the provisions of Art.18 NIP seemed to need a fully operational Assembly, something that wasn’t there then and isn’t there now.

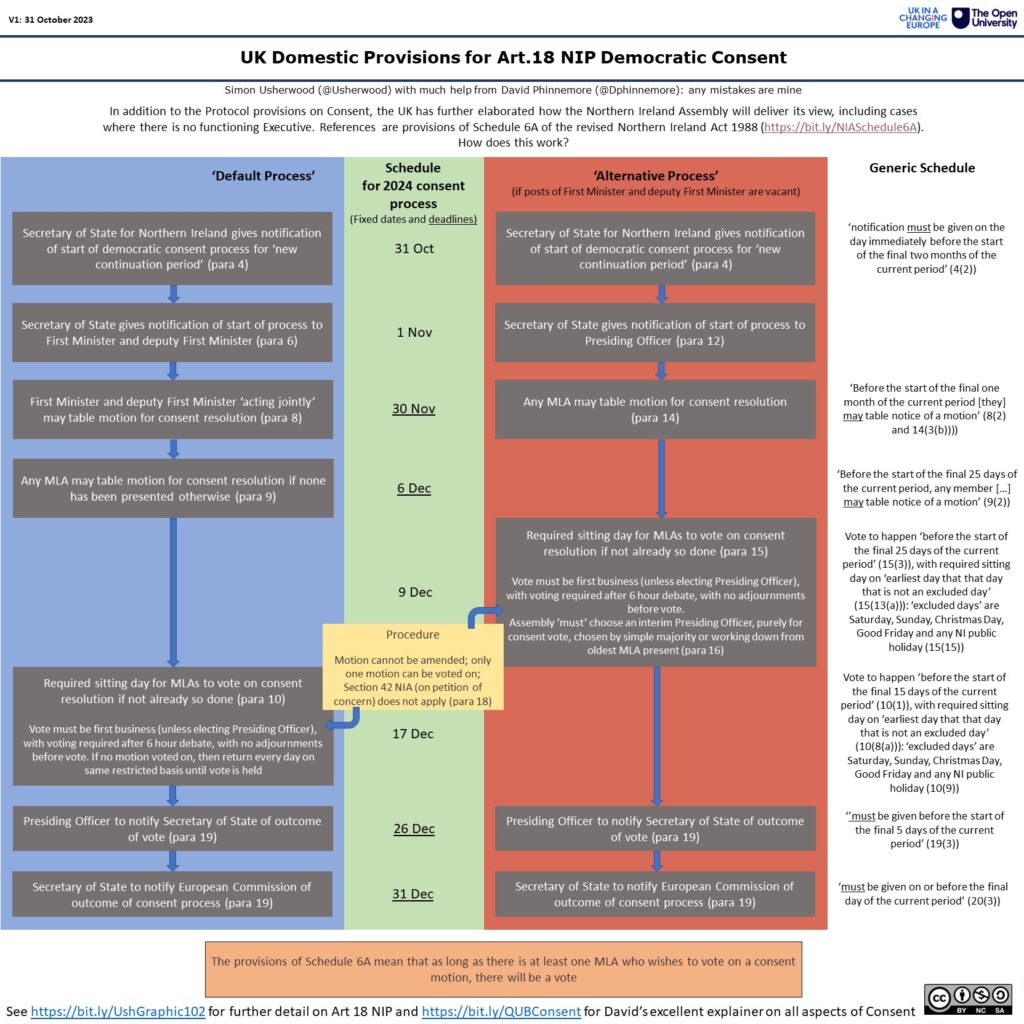

However, the subsequent domestic arrangements for meeting the obligations of Art.18 NIP have taken a much more robust line on trying to make sure that a vote happens in almost any circumstance.

As David Phinnemore sets out in his excellent explainer on this, the drafting draws on many years of Assembly filibustering experience to close down as many loopholes as possible once the process begins on Halloween 2024. Indeed, as long as there’s at least one MLA who wants a vote to happen, then it’ll happen, even if every other MLA doesn’t want it.

And even if it doesn’t happen, that still means the Protocol remains in force.

The only way that MLAs can collapse the Protocol is an active majority vote against it.

Of course, anything less than a robust vote in support will come with political implications for the Protocol: unionist opposition is one thing, but republicans and non-aligned ambivalence is another. Given that the Belfast/GFA model looks less than resilient in general, there is a non-negliable risk that the Protocol becomes another dimension of Northern Ireland’s political tensions, drawing it into any recasting of arrangements down the line.

However, this is a way off for now and all involved have other things to occupy them. That said, while Christmas 2024 might mean a moment to gather thoughts (and breath), the (probable) clearing of the first consent vote is unlikely to mark the full stabilisation of the Protocol or – by extension – of UK-EU relations.