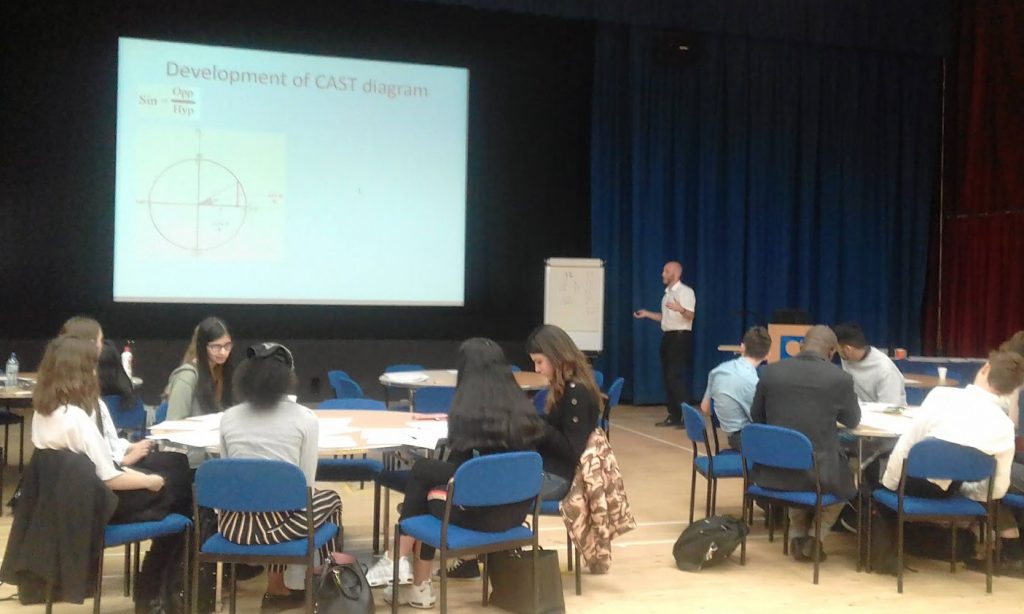

This blog is part of a conversation between Cathy Smith, Ruth Edwards and Jayne Webster, discussing a ‘mastery approach’ lesson. We have taken some topics from the conversation: setting a context, careful choice of language, different representations, small steps and reasoning.

Cathy Smith is from the OU, Ruth Edwards and Jayne Webster from Enigma Maths Hub based at Denbigh school in Milton Keynes. Ruth had invited Cathy to visit a lesson given by a visiting teacher from Shanghai in a local primary school. This is part of the NCETM UK-China Exchange national scheme where Shanghai and English teachers observe in each other’s classrooms. The lesson was about 3-digit column addition. It came at the end of a week of teaching in this year 3 class.

Setting a Context

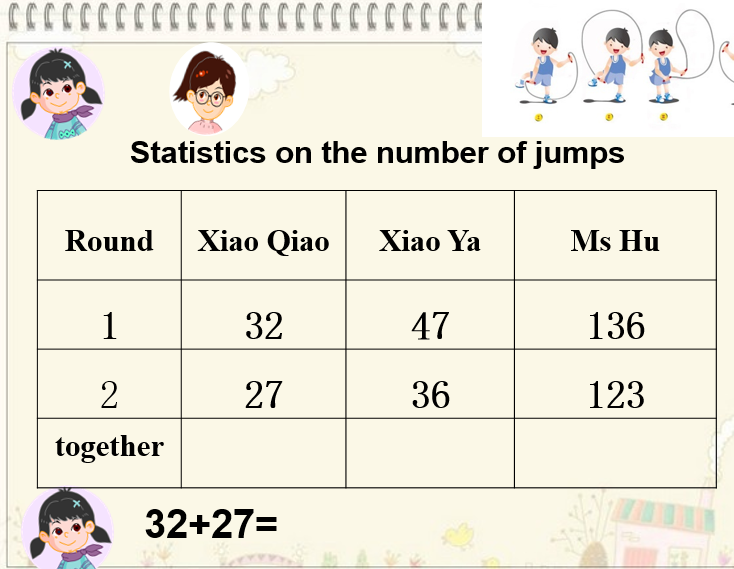

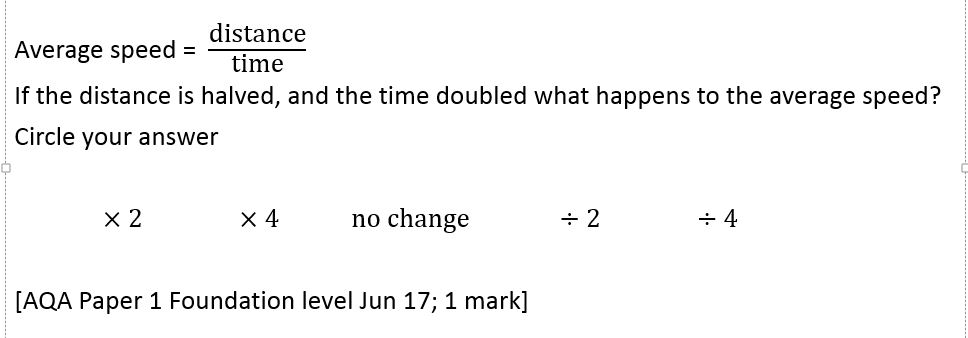

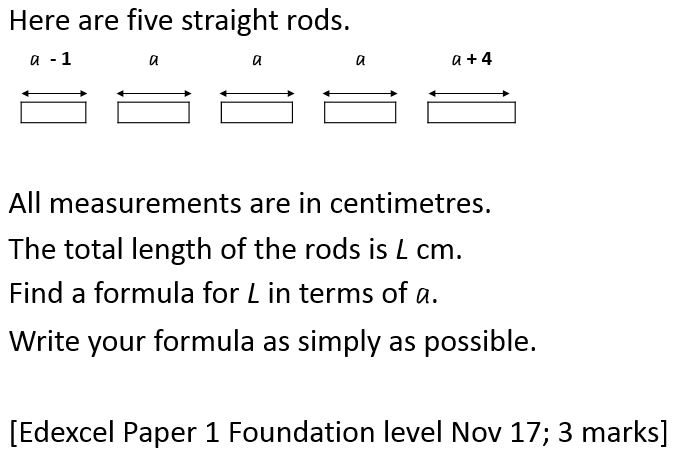

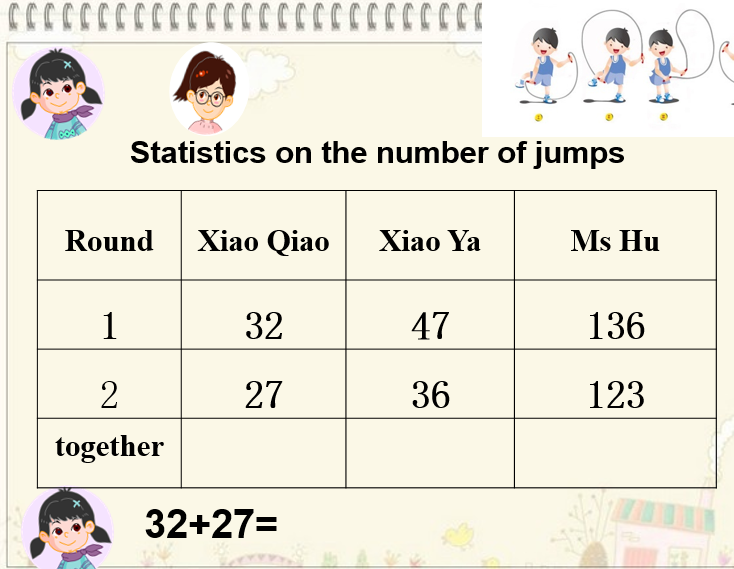

Cathy: I noticed at the beginning of the lesson that the teacher set a context for asking the questions. There was a skipping competition between students and they wanted to add up to find the total jumps, first with 2-digit numbers, then with 3-digits. They set up a reason for making these additions.

Ruth: That was certainly a feature of every single lesson that I saw in Shanghai. It always started with a problem set in context.

Jayne: I saw that at secondary level too, for every lesson. Even algebra, for example in teaching like terms, the teacher started with ordering breakfast and they were working with the number of spring rolls and the number of pancakes.

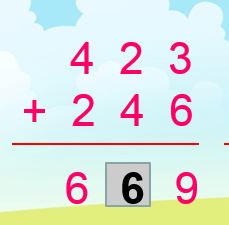

Ruth: The context was developed through the sequence of lessons. The first two columns here recapped the learning of the previous lesson, adding without and with exchange, and then the teacher’s jump column was a slight change to be the topic for this lesson. I notice that the Shanghai teachers use quite quick reviews that reinforce points from previous learning – just two questions.

Careful choice of language

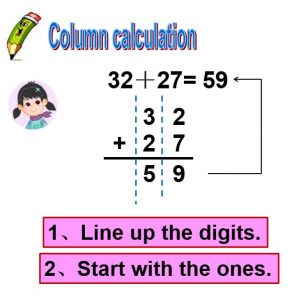

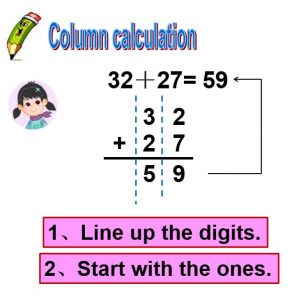

Jayne: What I liked here was the way the language that had been established in the 2-digit examples carried across to the 3-digit examples: Line up the digits. Start with the 1s. It made it really clear that this was an extension of that previous work.

Ruth: Yes, they had rehearsed the language in the previous lessons through the use of a stem sentence. Of course, if they were adding decimals they would start with the smallest digit and not the ones. So that isn’t quite general.

Cathy: It is one of the features that is emphasised in these lessons; choose your words and phrases carefully so that they communicate the mathematical thinking, and get the children speaking and repeating those phrases. But here, this is very procedural – line up the digits; start with the 1s. I can imagine my teachers from the 1970s and 80s saying exactly this. It is correct, and useful, but it is not helping the children put their mathematical reasoning into words.

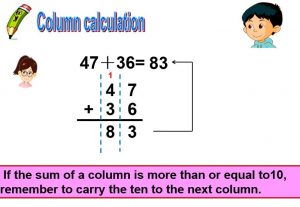

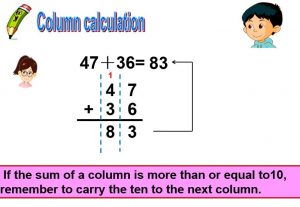

Jayne: But look at the next one. Here you have a whole sentence, with an ‘If ‘, so that is mathematical language about conditions. And the children are using correct mathematical vocabulary ‘more than or equal to 10’. They decided to use the word ‘carry’ rather than the mathematical word ‘exchange’ because that is what the children had met before.

Cathy: I agree: that’s a sentence with a mathematical structure. It uses language that is very specific to the representation – it’s about the procedure and the columns. Here the children are being told what to do, in mathematical language. But I’d say they are not reasoning yet.

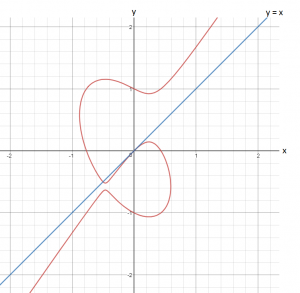

Reasoning in different representations

Ruth: I think those representations are important for reasoning. The children had had a sequence of lessons that focused on their understanding of place value. Pupils started by adding multiples of ten and they were saying 2 tens plus 3 tens is the same as 5 tens, and not using the language of twenty , thirty, etc. The children then moved onto 2-digit addition, initially with no exchange and then with exchange. So those mathematical small steps secured understanding of place value, then addition with no exchange, then with exchange, and then this lesson moved on to 3 digits. The lesson before the teacher had noticed that the children were not putting the answer from the column addition back into a number sentence, so she was reminding them that writing the number sentences out was important.

Ruth: One of the common misconceptions for vertical addition we would expect is that children add 20 and 30 and write 50 in the column, so there is an extra 0. Here in their previous learning they had talked about 2 ones and 7 ones is 9 ones, 2 tens and 3 tens is 5 tens so very few are making that error.

Cathy: But I am dubious as to whether we really want children to understand that as 4 tens rather than 40. There is an element of number sense in knowing that its 40. I totally agree that we don’t want children to read that as just a 4, even as a 4 in the tens column. We had such a lot of work in the 1980s about partitioning, about asking children to read 47 as 40 + 7 and 36 as 30 + 6. Then it can be added as 70 + 13 to make 83. That keeps the idea of the size or the value of the number. I suppose that if they are now being asked to say 47 is four tens plus 7; it does still keep its value.

Jayne: I think that’s what they do in Shanghai. In fractions, they stress the multiplication by the unit fraction. For example, it’s four of one-sixth and five of one-sixth is nine of one-sixth.

Ruth: And tied up with that, Cathy, in one of the earlier lessons they do both. They say four tens and three tens is seven tens when they do the column addition and say forty and thirty is seventy for the number sentence. They practice that movement between representations. The teacher emphasised that this worked for adding up any units – so it is generalised. You have to remember that now we are nudged towards the compact method of column addition. When it was the expanded method, then children could write the units and tens under each other and then add up those rows.

Cathy : I suppose, before we used to add up 4 and 3 in the tens column but that gave us no idea of the size of the number. Then adding up 40 and 30 meant that the children might write an extra 0 into the answer and get 803 or 7013. You are saying that adding up 4 tens and 3 tens keeps the size of the number and keeps the efficiency of the place value on the algorithm.

Ruth: In terms of conceptual variation, the children had been working with base ten materials. The exchange of a single ten to ten ones had been modelled physically in the concrete and then with pictures, and they had gone back and forward with those representations. That was part of the development.

Jayne: And comparing what’s the same and what different: four tens and three tens, forty and thirty. That is varying representations.

Ruth: It’s about exposing the structure that is common across the additions. And choosing your stem sentences that reflect the structure. So, you need good mathematical knowledge in order to choose those phrases.

Small steps and reasoning

Cathy: I know you talk a lot with teachers about the idea of taking small steps. There seems to be two levels of steps – lesson by lesson, or within a lesson. What is the difference between those?

Ruth: I think teachers are more confident in planning out the steps between lessons. What is harder is planning the small enough steps within a lesson. I think sometimes as teachers we know the task we want the children to get to by the end, but we haven’t planned the steps along the way. We have thought about task completion but not about what enables them to get there. This is something which the Chinese teachers do really effectively. Within lessons the learning is ‘step by step’ with pupils building confidence and competence.

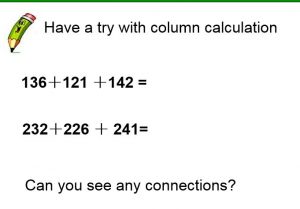

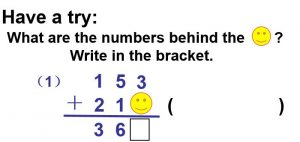

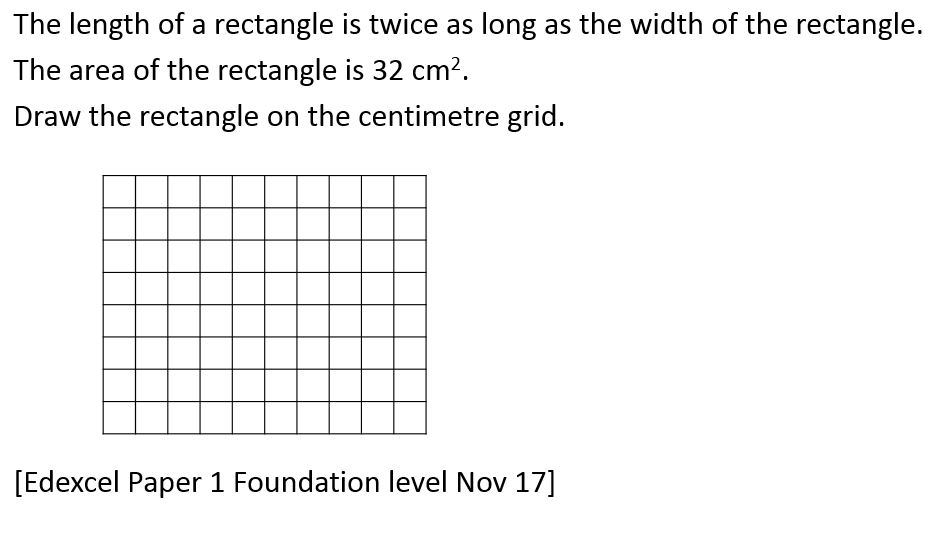

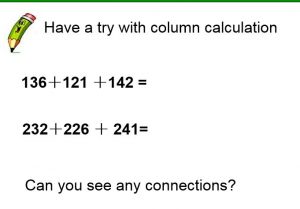

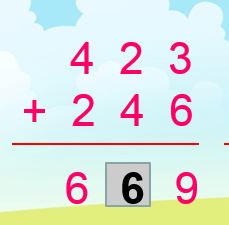

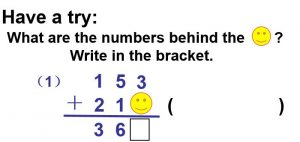

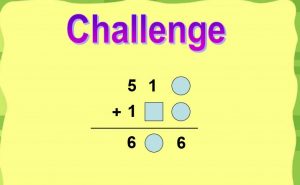

Cathy: So, is this what you would call the small steps here? First the move from 2-digit numbers to 3-digit numbers, then some examples where the children look for errors, then 3-digit additions with missing values.

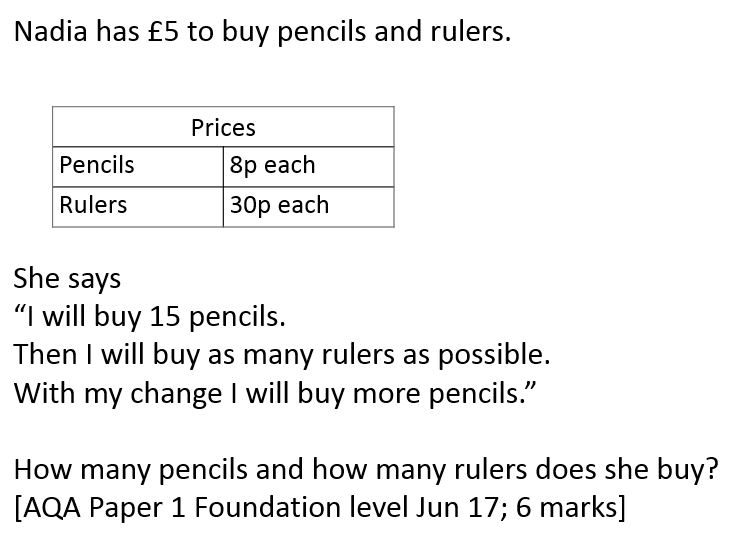

Ruth: So, you see this is important about mastery. Traditionally some children would never have got the opportunity to work with missing digits. Through the small steps more children are enabled to access the questions that require mathematical thinking.

Cathy: Why is it that in England our teachers would not have used a missing digits problem in the middle of a sequence of problems?

Ruth: I think that in the past we have had a perception of lids on children. We would have differentiated. These children will get here, these won’t and these might. It’s historical perceptions of groups of children.

And sometimes I think we were expecting too much and supporting too much. The small steps are also about the amount of time children are listening before they get to try for themselves. Sometimes a teacher would do some input maybe for fifteen minutes and be covering all the steps in one go, but then it’s a memory exercise for the children to remember all that when they go on to their independent work. For some of the children there is a nice adult who will sit and repeat it all with them, so they don’t need to listen, and they just stop expecting to be able to do it. With the small steps, most children are enabled to get it and they have the confidence ‘I can’ rather than ‘I can’t’.

Cathy: And I notice that here the missing number problem is put in when there is no exchange.

Jayne: Yes, to make it accessible. The reasoning question comes in earlier in the sequence of examples. Then they are more likely to go on and try something like this last problem that is more complex.

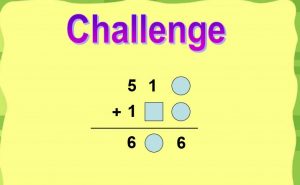

When I have done it with secondary, it has been the same. Everybody does the reasoning questions, a bit at a time and the whole class are at the same stage. The challenge will come, not just for the quick learners, but for everyone and when it is appropriate. That’s the cumulation of the small steps.

Cathy: But what about if we teach everyone with small steps all the time, when are they going to work independently? When they have to make decisions about what to do?

Ruth: That’s us developing how smart we are about leading pupils to be able to think mathematically within lessons and how the next lesson builds on this one. Chinese pupils look forward to the challenge in their learning (sometimes called Dong Nao Jing) and they feel empowered to tackle the challenges.

Jayne: Or about when they bring the same idea back but in a different context.

Ruth: Or about quick intervention. We do have to say that in China, they do have time to have an intervention during lunch or break or during the school day to work individually with those children who have struggled with that idea.

Cathy: Isn’t that consolidating the same skill? But what about if you wanted them to be able to do a reasoning question, like this one at the end, without that gentle warm up. At GCSE we want them to look at problems, something that is unfamiliar. Where is the transition between here, where everything is being made to seem familiar, to tackling unfamiliar problems?

Jayne: Yes, you do need to have that long-term view. You do need to introduce problem solving but I would say that here they are practising problem solving in a familiar context and that will make them more likely to be able to do it in an unfamiliar one.

Ruth: The big thing that I saw in all the lessons in Shanghai was that the steps are there for the children to take and the children take them. Here we are still at telling.

Jayne: Planning for the students to take the steps, not the teacher to take them.

Thanks to all involved for making the observation and the conversation possible.

Photo: Louise Cullen (Host teacher), Huihua Hu, Dr Debbie Morgan (NCETM), Yiyi Chen, Jayne Webster, Ruth Edwards.