Stuck for somewhere to go this summer? We’ve collected together some last-minute travel ideas from members of the OU Classical Studies community. If you’d like to add any more classical destinations to our list, please feel free to use the ‘Comments’ feature at the bottom of the article. Happy travels!

Trier, Western Germany (as suggested by Ursula Rothe)

If you want to combine glorious medieval architecture and continental urban sophistication with your visit to Roman antiquities this summer, look no further than Trier in western Germany. It has an intact late antique basilica (still in use), a Roman bridge (still in use), the ruins of two bath complexes and the famous Porta Nigra – a Roman city gateway that has remained intact because it was used as a church in the Middle Ages. It’s also a beautiful city with a twin cathedral and lots of nice cafes and restaurants. If you hire a car, the surrounding countryside is also full of interesting stuff, and not only because it is the Moselle Valley wine region: there is a huge, 23m-high Roman gravestone covered in reliefs from family life at a place called Igel; a rebuilt Gallo-Roman temple at Tawern; and a spectacular rebuilt Roman villa at Nennig.

Italica, Spain (as suggested by Paula James)

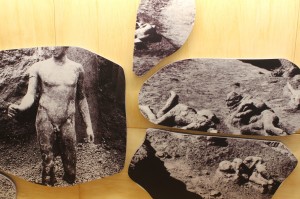

In summer 2001 our daughter Tanith, then resident in Madrid, arranged a few days’ stay in Seville and the three of us took the 50p bus ride to the Roman remains of Italica early in the morning. We were on our own for a couple of hours and I suspect it was a little visited site (and may still be!) but it was well worth it (vale la pena!). Hot and dusty (the surroundings and us!) we could only imagine what this walled town (home of emperors Trajan and Hadrian) might have been like in its heyday with colonnades, temples, baths, water features, theatre etc. Every house seemed to have had a mosaic and you got a real sense of this as a vibrant place to be from the time of Augustus. Standing under the baking sun in the arena of what was the third largest (and well preserved) amphitheatre in the Empire I found myself shuddering at what the prisoners must have felt as they stepped out onto the sand. The Ridley Scott movie Gladiator was a recent phenomenon and suddenly the scene in the provincial arena when the fear of the ‘performers’ was palpable rang horribly true. Sometimes keeping a critical and dispassionate distance which I had urged our students to do when studying the Roman Games at the Colosseum in A103 Introduction to the Humanities course is just not possible!

Pompeii, Italy (as suggested by Joanna Paul)

Given that Pompeii is already one of the most-visited archaeological sites in the world – attracting well over 2 million people each year – its inclusion on a list of recommended ancient sites might seem a bit pointless. Indeed, even if you can’t visit the site in person, there are a multitude of ways to do so virtually, whether it’s through blockbusting museum exhibitions like the British Museum’s ‘Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum’ (2013) or smartphone apps like ‘Pompeii Touch’. But having visited the site repeatedly over the past couple of decades, and after devoting a good deal of my research time to exploring its reception in the modern world, I couldn’t not make this my number one site to visit. Cliches and superlatives are applied to Pompeii with good reason – it is an awe-inspiring place, unrivalled for the scale and apparent immediacy of access to the ancient world that it seems to give us, and even a slog round the site in the heat of the summer sun in the company of thousands of other tourists can’t fail to have an impact. But a little extra effort is well worth it. The Pompeii that I love is the backstreet Pompeii, the quiet road that you stumble across when you’ve struck out beyond the Forum or the Via dell’Abbondanza, where the hubbub of tourist noise is suddenly replaced by the sound of cicadas, and Vesuvius looms at the end of the street, unimpeded by tourist-guide umbrellas and selfie-sticks. I’ve never really thought of Pompeii as a time machine that transports us magically back into the past (although many people do), but it is in these quiet and deserted spaces that contemplation of this ancient town – and of the distance between us and yet the close relationship that we seem to have with it – really becomes possible.

Unfortunately, this quiet contemplation isn’t easy to come by. Over the years, I’ve seen access to these Pompeian backstreets become ever more difficult, and the dream of stumbling across an empty house that you can wander around at leisure is often frustrated. Huge chunks of the site are invariably closed as the demands of staffing, and conserving, such a fragile site take their toll. But it can be done. On my most recent visit, in June this year, a lucky tip-off alerted me to the fact that the Via di Nola, heading towards the north-east edge of the site, was open beyond the usual barrier, allowing access to the House of Marcus Lucretius Fronto (see picture). Though hot, dusty, and footsore, we set off down the road, and were soon to be rewarded with a fantastic spell alone in this house, with its beautiful frescoes – by far the most memorable aspect of this trip for me. So, my advice to you is: don’t spend too long studying your map; instead, be prepared just to wander, to leave the tourist crowds behind as much as you possibly can – and if you turn a corner and a quiet road with no barrier opens up before you – follow it!

Naples (as suggested by Jessica Hughes)

If you do go to Pompeii, then chances are you’ll be staying in nearby Naples and making a day-trip to Pompeii on the Circumvesuviana train. Tourists often use Naples as a base for visiting other local destinations (Herculaneum, Cumae, Solfatara, Sorrento, and so on), but the city itself is an absolute treasure-trove for historians of every period.

One of my favourite sites is the Museo San Martino up on the Vomero hill. This is a kind of ‘Museum of Naples’, filled with paintings of the city and objects from its past, so it’s a great place to start getting to grips with Neapolitan history (as well as the urban layout, thanks to the gorgeous panoramic views – see the image above). Archaeologists will obviously love the National Archaeological Museum (perhaps the best museum in the world?), but there are also many other Greco-Roman elements of the city to explore, such as the Roman macellum beneath the church of San Lorenzo Maggiore in the historic centre, and the underground tunnels of Napoli Sotterranea (‘Naples Underground’), which can be visited as part of a guided tour starting from near San Lorenzo. And there’s always something new to discover: on my last trip I wandered into the Museo Duca di Martina at the Villa Floridiana which is dedicated to the decorative arts, especially 18th-century ceramics from the porcelain factory at Capodimonte. Lots of the objects in the Villa Floridiana depict classical scenes, and the imagery is often drawn from Pompeian paintings – a nice example of the close relationship that’s always existed between Naples and the other ancient cities in the region.

If you’re preparing for a trip to Naples, two popular history books that I’d recommend as preparatory reading are Peter Robb’s Street Fight in Naples and Jordan Lancaster’s book In the Shadow of Vesuvius. To find out about ancient Naples, you can download for free Rabun Taylor’s A Documentary History of Ancient Naples, and for an insight into how this ancient past has been appropriated in later eras, you can look at our edited volume Remembering Parthenope: The Reception of Classical Naples from Antiquity to the Present. There are lots of good websites devoted to the cultural history of Naples, and I’ve particularly enjoyed dipping into Naples: Life, Death & Miracles and Napoli Unplugged. Naples is one of the most heavily stereotyped cities in the world (pizza, traffic, chaos etc), but that’s partly why it’s so rewarding to go there in person – you’ll have many of your expectations confounded, and if you’re interested in ancient history and classical reception studies – well, you’ll probably discover a dozen new research topics in the process!

Amiens, France (as suggested by Cathy Mercer)

Just across the Channel, easy to get to, with a splendid Gothic cathedral, twice as big as Notre Dame de Paris which, remarkably, survived WWI intact. Jules Verne lived in Amiens and you can visit his house, complete with tower. There are lovely walks along the River Somme, through the Hortillonages, miles of marshy market gardens and parks, reached by charming little bridges.

Some may say that the delicious macarons d’Amiens are reason alone to visit and the delightful patisserie opposite the cathedral does a wonderful lunch. But why might a classics person would want to visit Amiens rather than Rheims or Rouen?

Why, for the outstanding archaeological display in Amiens’ museum, the Musee de Picardie, tagged by Amiens TI as a fantastic museum and they’re right. It has a really good Roman collection and a tremendous display of archaeological artefacts, carefully arranged in those lovely 19th century typologies so beloved by Pitt-Rivers and co.  For me the museum’s star exhibit was the beautifully displayed Amiens Skillet, a Roman enamelled bronze souvenir of Hadrian’s Wall found in Amiens in 1949. It shows soldiers with shields peeking through crenulations, conveniently marked up with names of the forts from Mais to Banna, Bowness to Birdoswald, maybe birthplace of St Patrick. There must be a matching cup waiting to be found out there, with forts from Vindolanda to Wallsend. The Amiens Skillet is similar in design to the British Museum’s Rudge Cup and lists the same western forts on Hadrian’s Wall. Another similar HW tourist souvenir is the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan found in 2003. The interesting difference is that the Amiens Skillet shows that the fame of Hadrian’s Wall had spread beyond the shores of Britannia. The museum is housed in a handsome chateau in the centre of Amiens and visits cost 5.5 Euros. This was clearly enough to put locals off because the only other visitors we met were two English ladies on a choir visit. The contrast with the crowds at the British Museum could not be more striking. Samarobriva, as Amiens was known in Roman times, seems to have been excavated in the main in the 19th century but there is remarkably little to see in town, except for a corner of the amphitheatre under a square and a block of flats named Samorobriva. For details of these and other places to visit see www.visit-amiens.com

For me the museum’s star exhibit was the beautifully displayed Amiens Skillet, a Roman enamelled bronze souvenir of Hadrian’s Wall found in Amiens in 1949. It shows soldiers with shields peeking through crenulations, conveniently marked up with names of the forts from Mais to Banna, Bowness to Birdoswald, maybe birthplace of St Patrick. There must be a matching cup waiting to be found out there, with forts from Vindolanda to Wallsend. The Amiens Skillet is similar in design to the British Museum’s Rudge Cup and lists the same western forts on Hadrian’s Wall. Another similar HW tourist souvenir is the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan found in 2003. The interesting difference is that the Amiens Skillet shows that the fame of Hadrian’s Wall had spread beyond the shores of Britannia. The museum is housed in a handsome chateau in the centre of Amiens and visits cost 5.5 Euros. This was clearly enough to put locals off because the only other visitors we met were two English ladies on a choir visit. The contrast with the crowds at the British Museum could not be more striking. Samarobriva, as Amiens was known in Roman times, seems to have been excavated in the main in the 19th century but there is remarkably little to see in town, except for a corner of the amphitheatre under a square and a block of flats named Samorobriva. For details of these and other places to visit see www.visit-amiens.com

We enjoyed a splendid long weekend in Amiens, with stop-offs at Boulogne for its splendid old town and riverside walk as far as the La Manche (English Channel). These stop-offs were in fact enforced by the rather eccentric timing of local trains – this meant that, apart from early morning and evening worker services, there is just one lunch time train to Amiens. But Boulogne’s medieval ramparts and fascinating Napoleonic connections are reasons enough to visit.

Samothrace (as suggested by Elton Barker)

The suggestions from my (esteemed) colleagues are all very good and excellent, but they’re all a bit too Roman for my liking. Perhaps that’s because there are simply so many places to go to in Greece that it’s difficult to choose a favourite – the sheer variety can be bewildering! Whether it’s the centre of the world at Delphi, or the wandering island of Delos, Greece is impossible to beat for the sheer joy of ancient monuments jostling for attention amidst stunning landscape.

A personal favourite of mine, and off the beaten track, is Samothrace. You’ll all know its most famous export, the Winged Victory of Samothrace (now in the Louvre): but you’ll possibly be less familiar with the site where it was found, the Sanctuary of the Great Gods (Hieron ton Megalon Theon). I guarantee that you’ll be blown away by the views. More than that, Samothrace is the alternative place to visit. The people are incredibly friendly, it has great camping facilities, and the walks through the forests provide a welcome relief from the heat (you can even take a dip in natural mountain pools – if you’re brave enough!). The question is, with all the choices Greece has to offer, do I go there again this year…?

Paula originally joined the OU in November 1993 and has made an enormous contribution not only to the life of the department, but also Region 13, where she worked as a Staff Tutor. Anyone who has studied or taught on an OU module dealing with the Roman world or Latin language over the last 20 years will be familiar with Paula’s work. She has written at all levels in her time at the OU, often – in true Paula style – choosing to work in close collaboration with central academic and Associate Lecturer colleagues. On the cultural side, she co-wrote A428 (The Roman Family) and the hugely popular material on the Colosseum for A103 (An Introduction to the Humanities), in addition to making distinctive contributions on topics as diverse as Roman reputations (A219 Exploring the Classical World), Roman North Africa (AA309 Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire), Buffy the Vampire Slayer (A330 Myth in the Greek and Roman Worlds) and Seneca (MA in Classical Studies). Her work on our language modules has included chairing Reading Classical Latin (A297) in production – a module that hit the headlines by attracting 1,000 students in its first year.

Paula originally joined the OU in November 1993 and has made an enormous contribution not only to the life of the department, but also Region 13, where she worked as a Staff Tutor. Anyone who has studied or taught on an OU module dealing with the Roman world or Latin language over the last 20 years will be familiar with Paula’s work. She has written at all levels in her time at the OU, often – in true Paula style – choosing to work in close collaboration with central academic and Associate Lecturer colleagues. On the cultural side, she co-wrote A428 (The Roman Family) and the hugely popular material on the Colosseum for A103 (An Introduction to the Humanities), in addition to making distinctive contributions on topics as diverse as Roman reputations (A219 Exploring the Classical World), Roman North Africa (AA309 Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire), Buffy the Vampire Slayer (A330 Myth in the Greek and Roman Worlds) and Seneca (MA in Classical Studies). Her work on our language modules has included chairing Reading Classical Latin (A297) in production – a module that hit the headlines by attracting 1,000 students in its first year.

, I’m now approaching the big half century and I’m a freelancer in the aviation industry, having previously served in the RAF. Before joining the OU I had no experience of university level education, having left school at sixteen with a clutch of ‘O’ levels. A trip to Rome reignited my childhood interest in the classical world and I began to read more about it. This was the point at which, with some trepidation, I decided to give the OU a go, over twenty five years since I’d written more than a couple of sentences together, never mind an essay!

, I’m now approaching the big half century and I’m a freelancer in the aviation industry, having previously served in the RAF. Before joining the OU I had no experience of university level education, having left school at sixteen with a clutch of ‘O’ levels. A trip to Rome reignited my childhood interest in the classical world and I began to read more about it. This was the point at which, with some trepidation, I decided to give the OU a go, over twenty five years since I’d written more than a couple of sentences together, never mind an essay!