AnnMarie McKenna and Catherine Scott

The AI Design Ed (AIDED) project began in 2024 with a survey of concurrent Open University design students, providing baseline data to support the main research aim of exploring the practical applications AI image generation tools within design education.

Survey findings showed student attitudes and understanding of generative AI image creation tools, their thoughts about future application of the technology, and importantly, their opinions on how these tools compare to conventional design visualisation tools. An earlier blog post by Sally Caird offers an overview of these first findings and their significance within existing literature.

From initial survey findings, we, AnnMarie McKenna and Catherine Scott two fairly long-in-the-tooth Associate Lectures in Design at the OU, formed a focus group of five wonderful design students enrolled on T217: Design essentials in 2024J, the core level 2 design module on the BSc Design and Innovation degree. We asked them to explore the practical application of Copilot in rendering visual communication, to seek ways that students could exploit AI in a transparent and ethical way.

Using completed TMAs from T217 as a foundation, there were two specific questions:

- Can GenAI faithfully recreate an existing design proposal?

- Can GenAI effectively communicate the context of a design problem?

Our goal was to show any relative advantages that Gen AI image creation tools offer students over conventional approaches to visual communication. Essentially; is it worth students’ time and effort?

We were mindful that GenAI should support design activities and not replace the designer’s voice in the design process, leading us to tasks where external intervention is accepted within design processes, such as activities within professional practice that can be conducted by a technician.

Note: Using GenAI as a creative ally is both an exciting and daunting proposition, but that is not what we were testing here, rather, trying to establish its worth as a ‘truthful servant’.

The first workshop task was to instruct Copilot to faithfully realise the designer’s vision, taking on the role of the visual communication technician.

Designing a chair is a rite‑of‑passage for all design students, and our focus group was no exception. They were asked to take their final chair design from T217 TMA01 and describe it to Copilot with sufficient detail to generate an accurate image.

The students found that very specific, objective descriptions did not reproduce faithful representations and took multiple iterations to get close to the original concept.

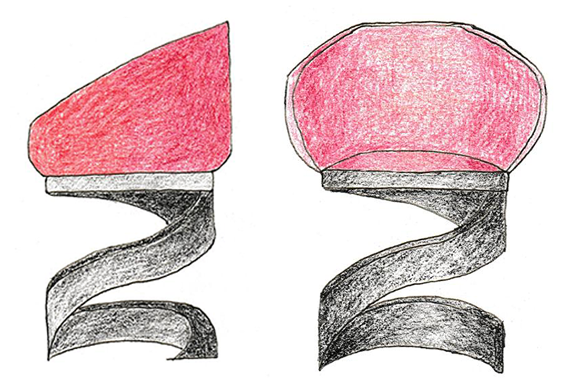

Starting with a seat inspired by the twist-up action of a lipstick (fig.1).

Figure 1. Original design (Lipstick chair)

The initial prompt given to Copilot:

“Red velvet seat. Wide spiral steel leg.

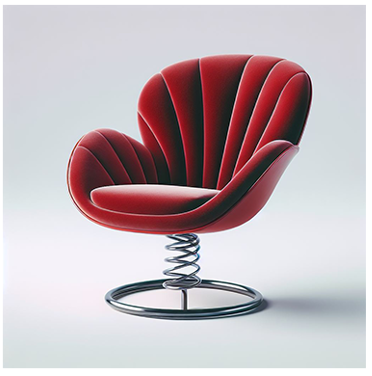

The chair must have a wide seat suitable for relaxation. It is ergonomic and offers a lot of comfort. It has soft curves with a high back. The chair leg is made of metal, spiral. It is solid and strong”. (see fig.2 for response)

Figure 2. Copilot’s first representation

The ninth prompt given to Copilot:

“Material: Red velvet seat. Wide spiral black leg.

The chair must have a wide seat suitable for relaxation. It is ergonomic and offers a lot of comfort. It has soft curves with a high back. Armrests must not be separated from the backrest. The base of the chair is formed by a very wide and thick spiral that supports the entire structure. The spiral is the only support for the chair.”

Copilot generated the following representation (fig.3)

Figure 3. Copilot’s final representation

Giving Copilot a chair concept, rather than a chair design description, often produced alternative solutions, showing a degree of creative input from the AI tool.

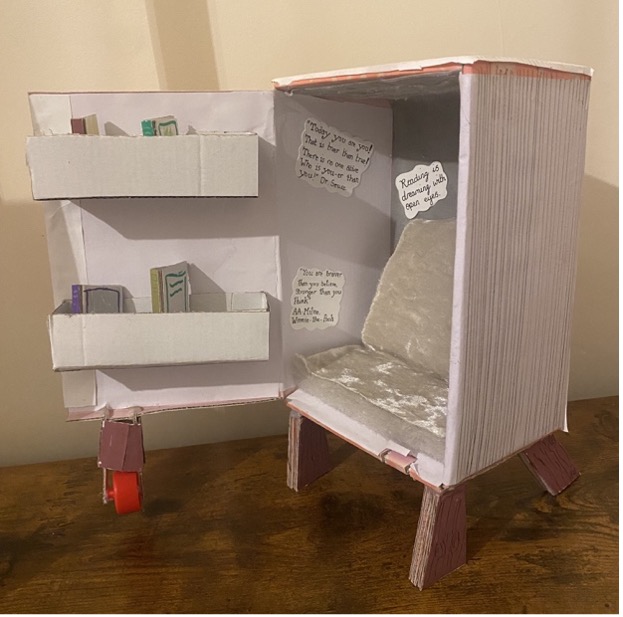

Figure 4. Original design for a children’s reading chair that looks like a book

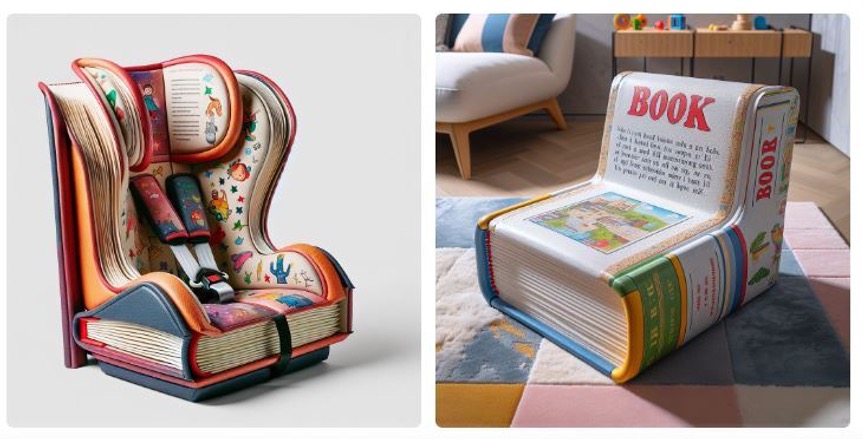

The above chair concept (fig 4) led to the initial prompt of: Design a seat for a child that looks like a book. Copilot generated the following responses (fig 5):

Figure 5. Copilot’s children’s chairs that look like books

For one student, when the original design proved too complex, a completely different concept evolved, following a more reciprocal process where the student adapted their prompts based on what Copilot appeared to understand.

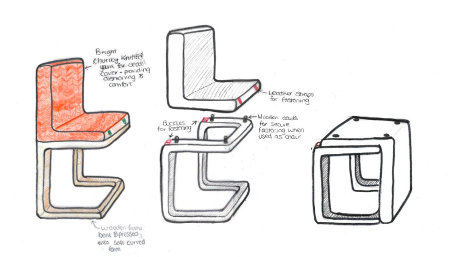

The original design: a chair for use in a knitwear manufacturer’s quality control area, to be multifunctional, fun and sleek with a form that allows the chair to tuck into a table with a shelf at the bottom…(fig.6)

Figure 6

…evolved into this idea (fig.7) after the following prompt: “can you design a chair that has a L shaped seat made from chunky knitted materials, sleek wooden legs in a bracket shaped form, the seat should be removable.”

Figure 7

The students had varying opinions on the ownership of these co‑authored creations; some liked the professionalism of the output, but felt it was too far removed from their main idea.

“I think I like how finished and complete the AI made the chair look compared to … drawing it by hand, but I don’t feel like I really got AI to a point … where it was exactly what I’d imagined”

Others recognised their own input and happily kept at least partial ownership:

“I … recognise that the picture has been created from my prompts going off my original design so in someways a small sense of ownership is felt for that.”

The second task was to coax Copilot into visually communicating a design problem. Designers will typically use collage, storyboards or their own images for this type of task, though more often internet search images along with text. Much like using the right keywords in a Google search determines the successful harvesting of effective imagery, the quality of GenAI prompts will determine the effectiveness of a problem representation; with the bonus of avoiding plagiarism, though we acknowledge the idea of image-based plagiarism using GenAI can muddy waters. This task, while not asking Copilot to design anything, did give the GenAI a degree of perceived creative agency.

Conversely to our findings in the first task, this time it seemed that higher specificity led to more accurate results with adjectives being the key to effective representations.

Two students had the following starting brief for their TMA projects: design a product to encourage and enable people living in towns or cities to grow their own vegetables.

While both found that initially Copilot offered solutions, they were eventually able to refine their prompts to effectively communicate the essence of the situation. For one student, a small change to the prompt significantly altered the impression conveyed (figs.8 & 9).

Figure 8. Prompt: person living in a city who wants to start growing vegetables in their home

Figure 9. Prompt: person in a flat living in a city who wants to grow vegetables but doesn’t know how

The other student working on the same design problem took 60 minutes, and a lot of prompt wrangling with Copilot, to settle on their final problem image (fig.10). Copilot struggled with the instruction ‘no artificial light’, often including grow lights in the image (perhaps it is like telling a person not to think of an elephant – then all they can imagine is elephants).

Figure 10. Prompt: “can you create a small kitchen apartment that is lacking floor and window space. there should be a large planter that is a failed attempt of growing vegetables on the windowsill, with no sign of life. … it should be a city environment through the daytime and look cold outside.”

The next student’s prompt, simpler to communicate, resulted in a very effective problem representation after just three attempts (fig.11). Issues with scale and tap positioning were noted, but the group agreed the problem was clearly communicated, despite these flaws.

Figure 11. Prompt: “Can you create a picture of a bathtub where the drain is clogged with hair and the water cannot drain properly? The hair must be at the bottom of the tub, above the pipe. The drain is not clearly visible. The hair must be just a few strands. The strands must be tangled in the pipe.”

To facilitate discussion/sharing of outputs, including images and prompts, we set up a VLE for asynchronous work and used Adobe Connect for synchronous discussions with the group.

To conclude, do we think GenAI image creation tools are worth students’ time and effort?

Yes and no.

We know that our AI image generation tool (Copilot) was effective in the communication of the sense of a thing (in our case an existing problematic situation) but it struggled with detail and could not faithfully recreate students’ designs (namely their chair concepts).

Interestingly, the student focus group identified opportunities for GenAI to help with creative problem solving, early in the design process, potentially removing the fear of staring at a blank page.

The AIDED project has both addressed and raised questions about the use of GenAI in design education, and we will now act on our students’ recommendation and explore the potential of co-ideation further in AIDED #2.

Watch this space.

AnnMarie McKenna and Catherine Scott

We extend our very grateful thanks to our T217 student participants, especially for their patience with Copilot’s occasional ‘wilfulness’.

#Design thinking, #GenAI, #Visual communication, #Creative agency

Leave a Reply