As an 11 year old in the early 70s, I was fascinated by the idea that the tiniest components of everything in the world, (including ourselves), had within them the power to obliterate the planet. I read avidly about the structure of atoms, and what they had the potential to unleash. The Cold War fuelled a dull terror which coloured many of my generation’s teenage years, bolstered by government advice as to what to do in a nuclear attack and culminating in the 80s with unforgettable dramas like ‘Threads’, or Raymond Briggs’ ‘When the Wind Blows’, which scarred us for life. Images of cultural institutions like British Homes Stores and milk floats being vaporised remained etched on our memories, whilst Ronald ‘Ray-Gun’ and his Star Wars programme brought science fiction into the real world. So when the Barbenheimer phenomenon hit the cinemas in the summer there was only one option for me!

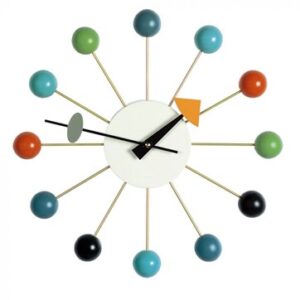

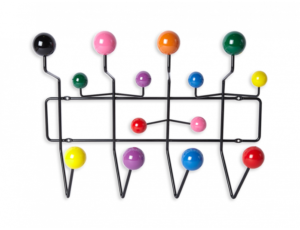

Despite the horrific loss of life caused by the atomic bombs, fascination, as well as optimism, as to what nuclear science might offer, led to an explosion of atomic inspired design during the 50s. Clocks and magazine racks were constructed with small coloured spheres on metal rods, like the atomic structures pupils build in chemistry lessons. Atomic particles became decorative devices on wallpapers, soft furnishings and kitchenware.

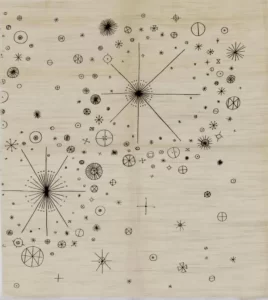

As the 50s progressed, this interest blended with a fascination with the space race and thus space related imagery also crept into design. Although a starburst shape had been present in lighting design since the late 30s, it had a renaissance with the launch of Sputnik in 1957, the first artificial earth satellite, which generated a fashion for dramatic light fittings like those by Gino Sarfatti or by companies such as Stilnovo. Sputnik itself looked like the visualisation of an atomic explosion.

On a much larger scale was the spectacular 335 foot tall Atomium in Brussels, designed by Andre Waterkeyn, and built as the centrepiece of Expo58, the first World’s Fair since the Second World War, and which has now become Belgium’s national symbol. Belgium was an early investor in the potential of nuclear physics, not least due to Uranium, mined in the Belgian Congo, being used for nuclear fission, including that used for the world’s first nuclear weapons. However, in choosing this structure for the Expo, Belgium wanted to celebrate how atomic research might improve lives rather than promote its destructive powers.

It’s no wonder there was excitement and optimism about science in the 50s and early 60s as new technology opened up new ways of living. Electric appliances revolutionised the lives of housewives, and men in white coats explained the science of everything from cornflakes and cat food to washing powder and toilet cleaner.

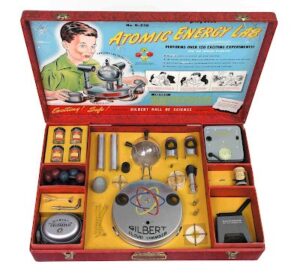

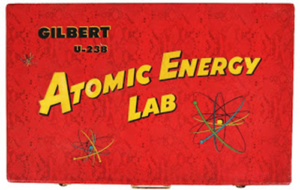

As more people got televisions, there was also a lot of science on our screens: ‘Tomorrow’s World’, Carl Sagan’s ‘Cosmos’, James Burke’s ‘Connections’ and ‘Young Scientist of the Year’ to name but a few. Science was sexy. Chemistry sets were highly desirable Christmas gifts for children although in 1950 there was a rather worrying kit on offer: ‘Gilbert’s U-238 Atomic Energy Lab’ with its ‘safe’ radioactive materials to create nuclear reactions. It included a Geiger counter and one of the suggested activities in the kit was to use it to play ‘hide and seek’ to find a radioactive sample hidden in the home!

With limited understanding of the effects of radiation, the testing of atomic bombs throughout the 50s was something of a spectacle. Civilians picnicked on hills for the best view. My uncle was one of the many military personnel who witnessed the tests on Christmas Islands in the late 50s. When the blasts went off, they protected their eyes with their hands. Terrifyingly, as others have testified, he told me how they could see their bones even with their eyes closed. Although investigations into the harmful effects of radiation had begun following the initial bomb tests in the late 40s, excitement about the potential of this new science seemed to brush over some of these concerns. Radiation was used to remove unwanted hair in beauty salons, and Fluoroscopes, or Pedoscopes, were installed in shoe shops to check the fitting of shoes on children’s feet. These were x-ray machines in wooden boxes, introduced in the mid-20s, and only finally outlawed in the 1970s (one can be seen in the London Science Museum). Assistants would manipulate the child’s feet within the machine to optimise the ‘reading’, and they, and parents could view the child wriggling their toes in the shoes through viewing portholes. A child might try on a number of pairs of shoes during just one visit, repeating the exposure, and of course again and again when they grew out of them and returned for new ones. Obviously it was a lot worse for the shop assistants. Cases of x-ray dermatitis were investigated (Kopp, 1957), and it is reported that one lost her leg after receiving a severe radiation burn (Sorrel, 2010).

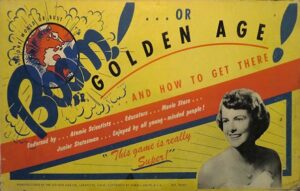

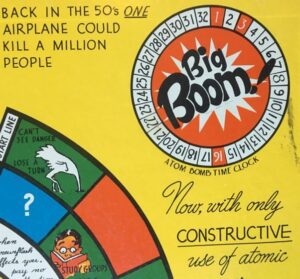

As a tutor on our design module, U101, where students are required to design a board game, I couldn’t end without including this jolly family game! ‘Big Boom!’ One player takes the role of the Atom Bomb and moves around a doomsday-clock circle while the other players move Nation pieces cooperatively on a spiral toward the goal of a single world government through the United Nations. If the bomb player wins, the world is blown up; if the Nation players cooperate effectively, they bring the world together in a new Golden Age. More details of this unusual entertainment can be found on Board Game Geek’s website.

Whilst there has been no obvious impact on design from the Oppenheimer movie this year, the broader Barbenheimer phenomenon did set off its own chain reaction, spreading a new strain of covid and, in interiors and fashion, an explosion of pink! But that would be for another post!

References:

The Atomium: (Accessed 28/10/23)

Davies, R. (26 September 2016), Was Threads the scariest TV show ever made? – BBC Culture (Accessed 24/10/23)

Gilbert U238 Atomic Laboratory: (Accessed 26/10/23)

Kopp, H. (7 December 1957), Radiation Damage Caused by Shoe-fitting Fluoroscope, British Medical Journal, (Accessed 26/10/23)

Sorrel, C. (16 November 2010), Vintage Shoe-Fitting X-Ray Machines Will Zap Your Feet (Accessed 26/10/23)

Washes Whiter (Episode 2): Big! Big! Big! (1990): (Accessed 26/10/23)

Leave a Reply