As part of Black History Month, The Smithsonian Institute’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation held a week-long webinar series, from 16-20 November 2020, about Black and other inventors of colour and Black technology consumers. The seminars also explored strategies for building a more equitable system of invention, patenting, finance and innovation for inventors of colour. You can see the complete programme at:

https://invention.si.edu/node/29159/p/661-program

I viewed two of the four sessions and below is a brief report on those sessions.

Black Inventors and Innovators at Work

Black inventors and innovators have developed many valuable technologies, from Elijah McCoy’s automated lubrication system for locomotives to Grandmaster Flash’s turntables and mixers. Black inventors have faced many challenges at work and in the market. The speakers discussed how aspects of Black identity can inspire technological creativity and how Black inventors have identified unmet social needs to develop new technologies. This session heard from two Black inventors who had overcome the challenges and had produced successful inventions and innovations.

Tyrone Grandison, Chief Technology Officer Pearl Long Term Care Solutions, spoke about his experience as a successful Black inventor faced with the historical institutional racism in the US innovation system. That system has failed to recognise the work of numerous Black inventors and innovators and has a patent system biased against non-white inventors that historically ruled that Black people could not hold patents. Grandison talked about his personal experience of the widespread practice of white-dominated organisations claiming the credit for Black inventions and the assumption that ‘inventors don’t look like me’.

He got started on his inventing and innovating journey by getting the opportunity to learn computer programming at a college in Jamaica, where he was born, holds a PhD from Imperial College, London and has now filed 27 patents in that field.

Tyrone said his main driving force for inventing were real problems that need solving, often arising from his lived experience. The latest project for his company involves creating a user-friendly computerised booking system for people wanting to find long-term care for elderly relatives and he mapped out his process for invention and innovation. First he said get clear on the problem; then consult users to identify the attributes of a good solution; then craft an initial solution and get more feedback from users. Iterate and improve the solution and finally introduce the innovation.

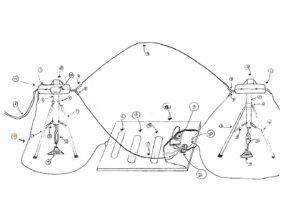

Tahira Reid Smith, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering, Purdue University then gave positive talk about her experience in becoming a successful female Black inventor. She said it all started with her extended New York family which she says was ‘perfectly designed’ to encourage creativity and innovation. She was encouraged to interact with people from all walks of life and witnessed her relatives coming up with creative solutions to their lived problems, such as redesigning shoes and organising car sharing. At school she was set the task of drawing something she’d like to have and sketched a machine for turning the ropes for ‘double Dutch’ skipping. This is a game and sport, popular among Black students especially, in which two long jump ropes turning in opposite directions are jumped by one or more players at once. Years later, after gaining entrance to study mechanical engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, when asked to think of a topic for a project in her undergraduate design course, she remembered the double Dutch machine. It was only because the (white) academic, Bert Swersey, who taught the course, knew about the double Dutch sport and encouraged her that she started designing the machine. Tahira ended up spending several years perfecting the design and she, Swersey and others were finally granted a patent in 2002. The device employs electric motors to rotate two ropes and a closed loop control system to synchronize the turning movements of the two ropes with an infrared beam used to monitor the use of the machine by the jumpers.

Tahira’s machine got widespread media coverage and a book Double Dutch, by Veronica Chambers about the invention was published. Tahira went on to do a PhD at the University of Michigan inventing a system for styling African American women’s hair without the usual heat damage. After post-graduation she eventually became Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering, Purdue University helping to found a laboratory for human-centred design and is a visiting NASA Scholar. Tahira was told she was ‘a square peg trying to fit into a round hole’ and credits her family background that made her different from most Black women as responsible for her success.

Commercialization and Institutions

Kara Swanson, Professor of Law and Affiliate Professor of History, Northeastern University School of Law in her presentation ‘Black Inventors, Equality and the Patent System’ talked about US history when patent law ruled that people of African descent could not have their inventions patented and slave owners routinely stole the inventions of Black slaves. It was not until 1821 that Thomas Jennings was granted the first patent to a Black inventor for a dry-cleaning apparatus. She then related the heroic efforts of Henry Baker, an assistant examiner at the US Patent Office, in documenting 400 inventions by Black individuals in The Colored Inventor: A record of fifty years (available free online via The Gutenberg Project).

Shontavia Johnson, Associate Vice President for Entrepreneurship & Innovation, Clemson University in her talk ‘Innovation is expensive’, like other Black individuals presenting in these seminars, stressed the importance of her family background in her interest in invention and innovation. For example, she witnessed her grandmother inventing a baby teething ring that met a Black community need. She views Black inventors as typically motivated by the wish to solve real community problems and maybe making money too. However, they face the huge barrier of the cost of patenting, which in the US averages $60,000, and then the much higher costs in developing an invention into an innovation, especially in high tech industries. So many inventions – especially those from Black inventors given prejudice by existing venture capitalists and others – don’t get patented and exploited due to the difficulty of obtaining finance.

If you are interested in finding out more:

All sessions were recorded and will be available on the Lemelson Center’s Black Inventors & Innovators: New Perspectives webpage in the weeks after 20 November 2020 at:

https://invention.si.edu/black-inventors-and-innovators-new-perspectives

You can also find more information from the Lemelson Center on Black inventors, including case studies, at:

https://invention.si.edu/tags/african-american-inventors

Leave a Reply