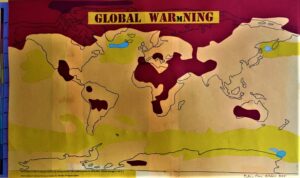

Image; Rise in average surface temperature 2048-2051 from 1951-1980 based on IPCC 4th Report, Robin Roy, October 2020

As you’ve probably heard, the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP) – called COP26 because it’s the 26th annual UN climate change conference since 1995 – will be held in Glasgow, Scotland from 31 October–12 November 2021. It will bring together heads of state, their ministers and officials to try to agree on targets, policies and actions to avoid dangerous climate change. A different state acts as president of each year, and the UK and Italy have the presidency of COP26.

The Conference of the Parties (COP) is the supreme decision-making body of the UNFCCC (the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) which is an international agreement to set the framework for global efforts to address climate change. All 197 States that are Parties to the UNFCCC will be represented at COP26 and decisions are supposed to be reached by consensus. The aim is to stabilise greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations at a level that ‘would prevent dangerous human interference’ with the global climate system.

During COP itself negotiations take place in an area, known as the blue zone, which is reserved for official delegations and those organisations that are accredited with UN observer status. There is also a green zone where more accessible and public activities occur, including exhibitions, side events and national pavilions.

There is general agreement that, since COP21 held in Paris five years ago, COP26 is the most important global meeting of governments to try to address the climate crisis. This is because COP26 is the meeting when the commitments made in the Paris Agreement at COP21 are due to be reviewed and significantly improved upon.

The 2016 Paris Agreement is an international climate treaty negotiated at COP21. The Parties agreed to ‘hold the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.’ Each Party is responsible for deciding its own emission reduction targets, known as ‘Nationally Determined Contributions’ (NDCs), which are not legally binding but must be reported on and made more ambitious (ratcheted up) every five years. 195 states have ratified the Paris Agreement, which requires both developed and developing countries to submit targets.

Many see COP26 as the last chance to act given that the existing NDCs are insufficient to avoid dangerous climate change, biodiversity loss and other impacts due to a global temperature rise of 2 to 3 °C by 2100. The Conference must also address other issues, including:

- Agreeing a $100 billion per year Green Climate Fund from developed to developing countries to help them mitigate and adapt to climate change.

- Setting the rules for carbon markets that will govern how emissions are traded between states and companies.

- Discussions on how to apply Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) for climate mitigation. It will focus on how, for example, tree planting and changed agricultural practices offer climate solutions for absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere.

Apart from being the place at which the NDCs agreed in Paris in 2016 are reviewed and ‘ratcheted’ up’, COP26 is considered as crucial to addressing the climate crisis because of two reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published in 2018 and 2021.

The 2018 IPCC Special Report Global Warming of 1.5 °C showed that the negative impacts of a 2 °C global average temperature rise were highly likely to be considerably more severe than those of a 1.5 °C increase. The Report said that the 1.5 °C target is possible but requires ‘deep emissions reductions in all sectors’ and ‘rapid, far-reaching, and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society.’ Global human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide ‘would need to fall by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching “net zero” around 2050.’

The IPCC Sixth Assessment report (AR6) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis published in August 2021 (IPCC, 2021) reinforced the conclusions of the 2018 report, but stressed even more urgently the importance of acting immediately to limit global warming to 1.5 °C. The report warns that in almost all scenarios 1.5 °C warming will occur in the early 2030s and that ‘unless there are immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, limiting warming to close to 1.5 °C or even 2 °C will be beyond reach.’

The UN Secretary-General António Guterres said the IPCC report was nothing less than ‘a code red for humanity. The alarm bells are deafening, and the evidence is irrefutable…We must act decisively now, to keep 1.5 alive.’

The UK has toughened its greenhouse gas reduction targets as the need to tackle the climate crisis has become increasingly urgent. In 2019 the Government changed the 2050 target from an 80% reduction in emissions compared to 1990 levels to ‘net zero’ greenhouse gas emissions. (Net zero was defined to mean ‘any emissions would be balanced by schemes to offset an equivalent amount of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, such as planting trees or using technology like carbon capture and storage.’)

In December 2020 the Government set a new commitment to achieving at least a 68% reduction in emissions by 2030, then in April 2021 set a legally binding target of 78% emission reductions by 2035 (including for the first time the UK’s share of international aviation and shipping emissions) compared to 1990 levels.

As well as its NDC committing to an at least 68% reduction in emissions by 2030, like the other Parties to COP26, the UK Government is required to submit a ‘long-term, low greenhouse gas emission development strategy’. It did this in October 2021 with a 360-page document titled Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener (HM Government, 2021). In the Executive Summary the Strategy did not mince its words on the need for action:

‘… if we fail to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, the floods and fires we have seen around the world this year will get more frequent and more fierce, crops will be more likely to fail, and sea levels will rise driving mass migration as millions are forced from their homes. Above 1.5°C we risk reaching climatic tipping points like the melting of arctic permafrost – releasing millennia of stored greenhouse gases – meaning we could lose control of our climate for good.’

The Strategy then set out how the UK would achieve its 2030 NDC commitment and move via 2035 towards the goal of reaching net zero by 2050. Policies for the period up to 2030 and beyond to reduce emissions while creating new jobs and encouraging private investment in green technologies include:

- 40GW of offshore wind by 2030, with more onshore, solar, and other renewables. A new large nuclear power plant and development of small modular nuclear reactors. By 2035 the UK will be powered entirely by clean electricity, subject to security of supply. (p. 19)

- For sectors that cannot be electrified, delivering 5 GW of hydrogen production by 2030 and halving emissions from oil and gas through use of hydrogen, biofuels, and carbon capture technologies. (p. 20)

- Grants of to encourage consumers to replace gas boilers with low carbon heating systems, mainly heat pumps. ‘An ambition that by 2035, no new gas boilers will be sold’. (p. 22)

- A ‘Hydrogen Village’ trial by 2026 to help decide on the role of hydrogen-fuelled boilers and heating systems. (p. 23)

- Ending the sale of new petrol and diesel cars by 2030. Grants to encourage consumers to swap petrol and diesel for electric vehicles and increased funding for electric vehicle charging infrastructure. (p. 24)

- Funding to increase use of public transport, cycling and walking, and to hasten the introduction of zero emission buses, rail electrification and city rapid transit systems. (p. 25)

- Investment to enable half of journeys in towns and cities to be cycled or walked by 2030. (p. 25)

- Support for the commercialisation of the UK sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) industry so people ‘can fly…without guilt’. An ambition to deliver 10% SAF by 2030. (p. 25)

- Support for the commercialisation of Greenhouse Gas Removal (GGR) technologies (such as Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage), aiming to move towards a private investment for developing these technologies (p. 28)

Despite this ambitious sounding strategy government critics are sceptical that the proposed investments and actions will be sufficient or introduced rapidly enough to meet the emissions reduction targets in time. The strategy places heavy reliance on technological solutions, private investment and voluntary action by industry and consumers. For example, the Net Zero Strategy says, ‘We will work with the grain of consumer choice: no one will be required to rip out their existing boiler or scrap their current car’. (p. 16)

- A lack of ambitious plans for insulating homes and other buildings There are 19m homes in the UK that need upgrading to be more energy efficient, but there is help for only a fraction of those homes. (There is a bit more on improving the energy efficiency of buildings in the Government’s Heat and Buildings Strategy (HM Government, 2021).)

- The strategy fails to make any recommendations about encouraging or incentivising people to change or reduce their consumption, and especially to reduce meat and dairy consumption.

- Although there are estimates of the greenhouse gas emissions reductions across broad sectors of the economy at different timescales (e.g., Transport), the strategy lacks detail on the reductions from implementing individual policies (e.g., grants for electric vehicles) and whether they add up to the UK’s 2030 commitment.

- There is no commitment to end new licences for oil and gas exploration, and to phase out fossil fuel production.

- The government plans to continue investing in new roads and airport expansions have been approved.

The climate activist Greta Thunberg vividly captured the sceptics’ view in a speech at the Youth4Climate summit held in Italy in September 2021 as part of the preparations for COP26. She lambasted not just the UK Prime Minister but all world leaders. She said: ‘…. Build back better. Blah, blah, blah. Green economy. Blah blah blah. Net zero by 2050. Blah, blah, blah…This is all we hear from our so-called leaders. Words that sound great but so far have not led to action. Our hopes and ambitions drown in their empty promises….’

I wrote this blog with COP26 due to start in a few days’ time. After the conference it should become clearer whether the world’s nations are serious about really acting on the climate crisis and not just making promises and setting targets.

Meanwhile you can learn more about and climate change and the environment on the Open University COP26 Hub, at: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/COP26

You may also wish to look at two excellent infographics produced by the Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit (2021).

COP26: A Visual Guide https://eciu.net/analysis/infographics/cop26-climate-infographic

A Short(ish) History of the UN Climate Summits https://eciu.net/analysis/infographics/un-climate-summits Accessed 20 October 2021

References

IPCC (2021) Sixth Assessment report (AR6) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-i/ Accessed 20 October 2021.

HM Government (2021) Net Zero Strategy: Build Back Greener, Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, October. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/net-zero-strategy Accessed 20 October 2021.

HM Government (2021) Heat and Buildings Strategy, Department of Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, October. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/heat-and-buildings-strategy Accessed 20 October 2021.

Leave a Reply