Introduction

A few years ago, while researching the persistence of traditional creative practices in Nepal, I heard about the Janakpur Women Development Centre, an NGO in Southern Nepal, where local women work on the preservation and re-use of traditional patterns and imagery used in agricultural rituals. The NGO aims to improve the quality of life of the women involved in the project. Having never been in that area, I decided to visit the NGO to know more about its activities and the context in which it was born.

Where

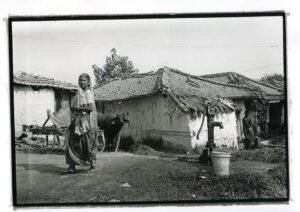

The ancient Kingdom of Mithila stretched from the Ganges in northern India to the foot of the Himalayas in Southern Nepal. This is a flat area with ponds, natural and artificial lakes and ritual pools, which function as a significant water reservoir at the end of the monsoon season.

Today the Mithila region is home to approximately three million people in Nepal alone, making Maithili the second most widely spoken language in the country. Like other communities in Nepal, the Maithili society is still informally but strictly divided into castes, despite the caste system being made illegal in 1962.

Janakpur is believed to have been the capital of the kingdom of Mithila from its foundation. Kuwa, the small rural village where the NGO is based, is located a few miles from Janakpur.

Roles and Rules

Traditionally, women from the Maithili community have rarely worked in official positions.

As it happens among many Nepalese ethnic groups that observe the rule of ‘virilocation’, women abandon their father’s house and move in with their husband’s family after their marriage. Since that moment, they spend most of their time in the courtyard (mandap), except for agricultural works that require their presence in the fields. Any contact between a married woman and men not belonging to her family group is considered “undesirable” (Campoli 2006).

Although many of the issues faced by Maithil women are similar to those faced by other communities in Nepal, “Maithil women are generally economic dependants on their families – first as daughters, then as wives and mothers, and often as widows” (Davis in Rousselot 2016).

“[T]raditionally and for the most part still today, Maithil women do not hold [nor can they pass down] significant property, nor retain control over their own incomes if they have incomes. Their labour is in service to their husbands’ families” (Davis in Rousselot 2016).

Women’s movements, communications, and daily habits are tightly regulated. Women spend most of their time at home, and the domestic courtyard is where most female activities, family life, and the main village rituals happen.

This home-centric culture has also resulted in the development and preservation of a particular artistic tradition, passed down from generation to generation, from mother to daughter.

Mithila Art as Domestic Art

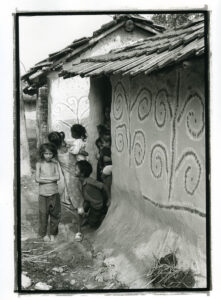

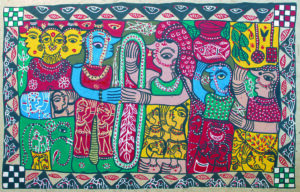

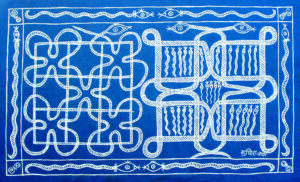

The art of Mithila is a visual representation – more or less figurative and often abstract and symbolic – of the seasonal and agricultural cycles and the rituals connected to them. The paintings have the function of conveying the deities’ blessing on the house where they are painted (Campoli 2006).

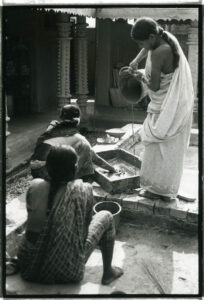

Producing the paintings is a ritual itself that only women can perform. The complex scenes and symbols are painted on the walls of the traditional mud houses or the dusty floor of the courtyards. They have an ephemeral nature and are supposed to be washed out by the monsoon rain.

When the rains do not destroy the paintings, they are covered over with a new layer of mud plaster during the celebrations for the New Year (Juristal), leaving the walls as a blank canvas for the following ritual.

From Earth to Paper

Interest in the Mithila paintings, starting from the 1960s, increasingly impacted the Bihar area – in India. However, in Nepal, the same tradition continued to persist in relative obscurity.

It was only in 1992 that the Janakpur Womens’ Development Centre (JWDC) was founded in Kuwa, a small village on the outskirt of Janakpur, along with other projects focused on improving the region’s economy. The JWDC’s aims were to use existing creative skills to give local and marginalised women support and income-earning opportunities outside the home, help them gain independence, a role in society and a voice of their own.

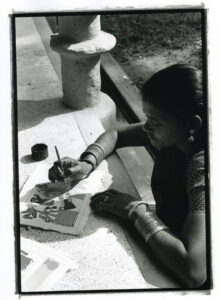

The ephemeral wall paintings were transferred onto paper to create sellable artefacts.

Creativity and Opportunity

At JWDC, women received marketing, management and language training. They also learned to make the paper for their paintings, to be fully self-sustainable.

This strategy aims at empowering local women using their existing skills and helping them to become economically active members of society. The founder kept the supervision on the centre, which eventually became a local NGO with a local woman as a president.

“The artists themselves run the NGO and market their art. So, they become the beneficiaries of profit from the sales,” said Aava Suman (Suman in Thapa 2016), president of JWDC. According to Suman, JWDC, building its foundation upon the rich artistic heritage of Maithili women, provides training in management, leadership, gender awareness and basic business skill (Thapa 2016).

After a challenging beginning (some of the women wouldn’t speak, and they always had to have a male chaperone with them) and the initial opposition of the local villagers, the centre started employing more and more women from the nearby villages in a variety of crafts. Paintings and decorated objects began being sold in shops in Nepal’s main cities – Kathmandu, Chitwan and Pokhara – and later abroad.

“These women broke the ground; now there’s been some societal changes and more women are gaining independence, but these women really had to fight at the beginning; it wasn’t an easy thing” (Burkert in Rousselot 2016).

When I was at the centre and spoke with some of the women working there, they confirmed that they felt empowered by having an active role in their family and the village economy. Mothers can pay for their children’s schools. Wives can buy small plots of land to improve their family status. Widows – that, after the death of their husbands’ ‘belong’ to the husband’s family – have stopped living in fear of being repudiated and becoming outcasts because they can provide for themselves. Some women have also left the centre and opened shops or engaged in international selling on their own.

Overall earning money through their own art has made it possible for those women living in small rural communities and in an extreme disadvantaged situation being proud of themselves, feeling empowered and breaking gender stereotypes in the Nepalese society.

An interesting – and symbolically important – evolution in terms of art production is that Mithila art, which was once anonymous as most forms of traditional ritual art, is now associated with the name of the women who produce the piece. Women have started signing their work and developing their own style, which means coming out from the shade in which they were relegated and becoming an ‘individual’ who deserves to be recognised as a person.

Conclusion and Final Reflection Points

Although JWDC and other similar initiatives have undoubtedly improved the lives of many women, helped create change within the community, and positively impacted the local economy, there has yet to be a radical change in the social structure. Access to education is still very limited – especially for girls and for some of the marginalised groups – and the majority of women still live a recluse life.

However, several positive points can be outlined:

- Born as a training centre, the strength of JWDC was combining traditional artistic skills with commercial demand.

- The diffusion of Mithila artefacts helped draw attention to that particular style and through it to several social, economic, and cultural issues that impact that area, fostering debates and local and international initiatives.

- The centre provides women with art training butt also with management and business skills, giving them a choice. They can either keep working for the centre or leave and set up their own business.

To conclude, why do I think this case study is important, not only in relation to Nepal, but to a wider context?

Because all the points outlined above can be transferred to other cultures, geographical areas and activities when creating or promoting social initiatives:

– the connection between local culture and tradition with the current market;

– giving the weaker and marginalised elements of a group an active role in society;

– providing them with specific skills but also with the business and management skills that they need to promote themselves;

– breaking stereotypes;

– promote the economy of a rural area through the preservation of local traditions while connecting it to the global context.

Link to the JWDC website:

https://jwdcnepal.org/

References

Burkert, C. (1997) Janakpur Art: A Living Tradition. Kuwa Village, Janakpur: JWDC.

Campoli, A. (2006) Ritual Art of the Kingdom of Mithila: Traditional Paintings by Janakpur Women in Nepal. Kathmandu: Vajra Publications.

Fleury, H. (2003) Les Peinteurs du Mithila (Inde, Nepal) au Coeur de Mutations entre Rituel, Art et Aritsanat.

Rousselot, J. (2016) Nepal’s Maithil women break traditional gender roles. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2016/06/nepals-maithil-women-break-traditional-gender-roles-160626115132870.html

Thapa, C. (2006) Mithila Art Sculpts Businesswomen in Nepal. Available at: http://english.ohmynews.com/ArticleView/article_view.asp?menu=A11100&no=284899&rel_no=1&back_url=

Vequand, Y. (1977) The Women Painters of Mithila. London: Thames and Hudson.

Image Credits

Photos by Alessandra Campoli.

Leave a Reply