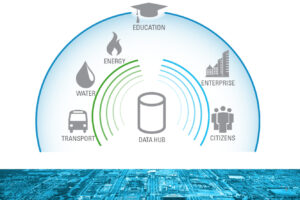

Since its inception over a decade ago, the smart discourse and its promoters have been incredibly successful to the extent that now many cities identify themselves as smart cities. While there is no single definition of a smart city, in broad terms such developments are based on digital infrastructures comprising sensors and data hubs which present data in various ways via city dash boards and smart phone apps to assist decision making and augment city management.

Smart city developments have been widely critiqued for their capacity to surveil urban populations and perhaps edit their choices in pursuit of opaque notions of urban progress, inflected by corporate interests. However, it is difficult to deny that new knowledge gained through smart city initiatives can be useful in city management. On one hand we may be reluctant to share our travel patterns with transport management databases, on the other when we are hurrying to appointments, we are grateful when we can follow routes through a city which minimise congestion.

If we excavate smart city initiatives more deeply, we can see many people are ultimately concerned that smart decisions undertaken in pursuit of the modernist ideal of ever ‘greater efficiencies’ are not automatically wisedecisions. For example, smart city initiatives may identify efficient transport routes but tell us little about the lived experience of making journeys – smart cities may tell us that it is efficient to travel from Milton Keynes to London at 23:52 on a Sunday evening but they do not tell us much about the lived experiences of making that journey – how the affects such as atmospheres on the railway station platform may lead to concerns about safety and security.

There is growing concern that smart city initiatives and subsequent artificial intelligence based developments hold potential to shorn cities of their profoundly human attributes which cannot be expressed numerically and managed in that vein. For example, as suggested above there are times when we need to travel in efficient manner but there are also times when the act of travelling (e.g. embodied in the idea of touring) is more important. Here, people are not simply users which can be portrayed as part of transport systems in instrumental fashion but ‘travellers’ for whom both the efficient operation of transport systems is important as well as the affects of journeying and corporeal experiences of urban life.

Such limitations of smart city developments are clearly a matter of concern. Why do these limitations arise? What can be done to help resolve them?

Founded on modernist inspired notions of efficient urban living, it is hardly surprising that smart city developments are based on what is often called ‘data science’. Drawing on the ancient Greek intellectual virtues, we can observe that smart cities thus embody scientific thinking – episteme, which can be characterised as scientific knowledge, universal, context independent, invariable. Based on analytical rationality, episteme provided the intellectual foundations of much 20th century urban planning. In practice, this resulted in ‘Black Boxed’ scientific ways of knowing cities (e.g. models) which were more or less the sole preserve of planning technocrats. And there are now serious concerns that smart city developments hark back to such arrangements and in time that the episteme of the smart city begins to dominate city governance and foreclose other ways of knowing and acting in the inevitable struggles to represent, plan and manage cities.

Although such arguments about knowledge politics can seem a little abstract, these aspects of urban governance cities matter. Cities are complex and challenging to represent in meaningful ways. In planning processes, as Ash Amin observes, we ‘summon up’ cities and as there is not a singular criterion against which we may objectively determine the validity of such representations, their construction is profoundly political embodying power relations which shape who gets what.

In representations generated by smart city initiatives, which may be summoned up in urban planning processes, the measurement of phenomena (e.g. of flows such as energy and traffic) is prioritised. Such logics are embodied in the phrase ‘what gets measured gets managed’, which signal development priorities and potential patterns of investment. However, residents may be unable to narrate their felt needs by drawing on a data science discourse but nonetheless have valuable local knowledges and understandings that are of immense value in urban development. It may also be the case that even if residents could narrate their concerns using a data science discourse, such approaches would be inappropriate as their quantitative foundations mean they are incapable of representing residents’ views in a meaningful way.

Thus, being smart may be useful to help manage aspects of the technical systems which underpin everyday life in cities. But ultimately being smart may be insufficiently socially inclusive for wise city planning and governance. if we are to achieve socially progressive more sustainable urban development, we must ensure that other ways of thinking about and representing cities are not marginalised in city planning and management. This means planners need to learn when smart city knowledge is valuable and how it can be usefully joined in planning processes, with other forms of knowledge generated by ways of knowing which do not necessarily conform with the epistemic principles of data science. Ultimately deliberate action is required to ensure modes of thinking other than ‘smart’ quantitative episteme thrive in cities and ensure many voices (human and non-human) are heard and make a difference in urban governance.

For a fuller discussion of these issues see: Cook, M. and Karvonen, A. (2023) Urban Planning and the Knowledge Politics of the Smart City. Urban Studies available online

This blog post benefits from insightful comments provided by Dr Miguel Valdez.

Leave a Reply