Georgy Holden’s post last week got me thinking. Do have a look at it. Georgy made a link between the philanthropic housing activities of the 19th century ‘model village’ builders and the lessons for today with the push for the private sector to build vast amounts of new homes. She is so right that there is a lesson about needing to go beyond the simple provision of housing with an understanding of the social, psychological and cultural needs of the residents to create a healthy and thriving society.

Georgy Holden’s post last week got me thinking. Do have a look at it. Georgy made a link between the philanthropic housing activities of the 19th century ‘model village’ builders and the lessons for today with the push for the private sector to build vast amounts of new homes. She is so right that there is a lesson about needing to go beyond the simple provision of housing with an understanding of the social, psychological and cultural needs of the residents to create a healthy and thriving society.

Yet how might such an approach become the design norm rather than the design exception? The philanthropic industrialist built only a handful of garden villages at the end of the last century. Most subsequent urban development ignored them as worthy but utterly unaffordable for normal housebuilding. Government regulation did improve housing standards, but as land prices increased then, even with development densities rising, buying a house has slid beyond the range of so many people. ‘Generation rent’ has been the result, and even then, rents for decent city properties are often out of the reach of many. Generation ‘stay at home with Mum and Dad’ is upon us too.

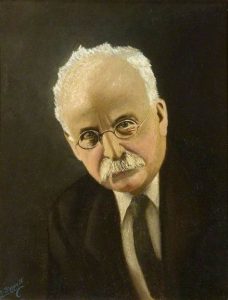

There is another historic lesson that we could draw upon here. This is about the institutional process that facilitates good design. When I first joined the OU as a PhD student in 1974, my research was on the design of the New Towns. Ebenezer Howard is well known as the father of the Garden Cities. These directly led on to the New Towns programme, of which Milton Keynes is a prime example. The Garden Cities at Letchworth and Welwyn applied the holistic design community principles from their industrialist-funded Garden Village forebears, but did not depend on lavish philanthropic funding. Howard’s key contribution was to devise a property development process that provided the resources and impetus to build and support all that was needed for a new community. A charitable trust would buy the development land at rural cost, plan the Garden City, service sites and lease them to developers. The charitable trust would keep the freehold and so get a stream of income as land prices increased, which could support social development action.

There is another historic lesson that we could draw upon here. This is about the institutional process that facilitates good design. When I first joined the OU as a PhD student in 1974, my research was on the design of the New Towns. Ebenezer Howard is well known as the father of the Garden Cities. These directly led on to the New Towns programme, of which Milton Keynes is a prime example. The Garden Cities at Letchworth and Welwyn applied the holistic design community principles from their industrialist-funded Garden Village forebears, but did not depend on lavish philanthropic funding. Howard’s key contribution was to devise a property development process that provided the resources and impetus to build and support all that was needed for a new community. A charitable trust would buy the development land at rural cost, plan the Garden City, service sites and lease them to developers. The charitable trust would keep the freehold and so get a stream of income as land prices increased, which could support social development action.

A state-owned version of this model was used in the New Towns, where the New Town Development Corporation had compulsory purchase powers for all development land in its area and so made money from selling serviced sites. However, they sold off the freehold and so the model became simply one that served the initial stages of development. All the New Town Development Corporations were just temporary institutions, so their community development approach was transient.

There are lessons for today. The institutional structures behind good design are as much of a design process as the physical designs they support. Ebenezer Howard cleverly designed an urban development institution in which private builders could thrive by building good quality and affordable housing. They were not reduced to mere contractors (as in the case of council estates) or nationalised in a state takeover. It was neither capitalist nor socialist, but an entirely alternative approach. Perhaps what is needed now is to apply such radical 1900s thinking to our 21st century urban development challenge. Otherwise the ‘stay at home with Mum and Dad’ might be here to stay!

Leave a Reply