I am Daniel Chapman a PhD researcher with the OU under the supervision of Nicole Lotz, Katerina Alexiou and Theodore Zamenopoulos. In my research, I interrogate and investigate the intricate and delicate problem that is Serious Youth Violence and social media. I am interested in the ways in which social media platforms generate, manipulate, and cause serious offline violence amongst youth.

After the lockdowns caused by the coronavirus pandemic, we saw some of the highest levels of violence in London. We also saw some of the highest social media usage societies globally (Cho, et al., 2023). One could naturally put this down to the fact that we had to stay in our homes, to feel connected many of us turned to social media to communicate with friends and family. Social media has some amazing benefits, it has made some of the youngest millionaires our society has ever seen. For example, in the short space of 2 to 3 years, the youtuber who goes by the name of Mr Beast has amassed such a fortune, he is now using part of this fortune for philanthropic aid, such as bringing electricity to rural communities in Africa (Lectric Ebikes, 2023), or paying for laser eye treatment of 1000 people so that they may see.

While social media has become an integral part of modern communication, its potential negative influence is only beginning to be thoroughly researched, particularly regarding its impact on youth violence. This is likely due to the relative novelty of social media as a widespread communication tool. However, a concerning trend has emerged: a rise in serious youth violence across various communities, regardless of socioeconomic background or ethnicity. Notably, 2023 witnessed a surge in such violence in London, reaching levels not seen since before pandemic lockdowns (Overton, 2024). This suggests a potential link between the increased social media usage during lockdowns and the observed escalation in offline violence.

Figure 2, Mr Beast Youtube Millionaire

There are many ways in which social media may cause serious youth violence offline. One of the more prolific is that of gangs’ usage of social media. Gangs can be defined as a persisten group of people engaged in criminal activity, violence and territoriality; they also have a strong sense of belonging within their groups. Gangs communicate and taunt each other 24/7 online. There is no respite in their gang feuds. Rappers share songs on YouTube detailing (in slang) serious acts of violence that they have committed towards their ‘enemy’ (Fernández-Planells, Orduña-Malea, Feixa Pàmpols, 2021). This in turn creates a domino effect, continuously these gangs are committing acts of serious violence against each other and uploading songs detailing this to taunt the other gang. This only escalates the violence as someone must continue this serious offline violence until a fatality has been committed, which in turn creates more fatalities between gangs (Patton, et al., 2016), as the feeling of being ‘violated’ continues between each other (Elsaesser, et al., 2021).

But I would implore society to look beyond this obvious narrative. Although, gangs do use social media, and this is a cause of serious offline violence (Storrod & Densley, 2017). Murders were committed by youths who are not in or have never been in gangs. These acts of serious youth violence were connected to their social media usage. The murder of Brianna Ghey, a 16-year-old transgender girl who was brutally attacked by two young people who had prolonged communication planning her murder on social media platforms (Pidd, 2024). The murder of Oliver Stephens, who was murdered after a falling out on the social media platform snapchat (BBC News, 2022). Both murders have similarities in the sense that they were ferocious, also the fact that social media mediated and or generated both serious acts of youth violence that resulted in fatalities, but they were not committed by gang-initiated youths.

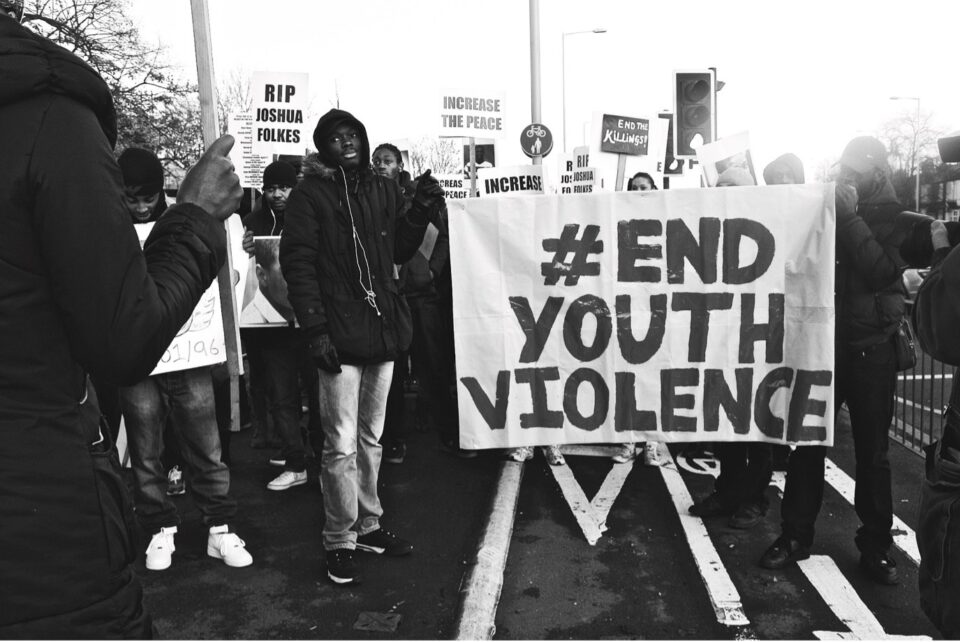

Figure 3, Protest to end youth violence

I will be entering the field research stage of my PhD this year. While much research has interrogated the problem few studies put youth at the centre of the investigation, as active participants. Understanding youths’ perception why potentially social media generates serious offline violence, is key to reducing Serious Offline Youth Violence in connection to social media usage. My research takes a mixed method approach borrowing themes from multiple disciplines surrounding youth studies. Although at the heart of the research is a design led approach, utilising methods that designers have used to create meaningful research in the past. After conducting semi-structured interviews with participants. Through co-design, we will explore possibilities for creating a more positive social media environment. This will involve brainstorming solutions to minimise the potential for social media to be used in ways that incite violence.

References

Storrod, M. L., & Densley, J. A. (2017). ‘Going viral’ and ‘Going country’: the expressive and instrumental activities of street gangs on social media. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(6), 677–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1260694

Pidd, H. (2024). Brianna Ghey’s Teenage Murderers Named before Sentencing. The Guardian. [online] 2 Feb. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2024/feb/02/brianna-ghey-murderers-named-sentenced-to-life-in-prison.

Olly Stephens: Concerns about killer’s violent nature raised before killing. (2022). BBC News. [online] 21 Dec. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-berkshire-64045457.

Fernández-Planells, A., Orduña-Malea, E., & Feixa Pàmpols, C. (2021). Gangs and social media: A systematic literature review and an identification of future challenges, risks and recommendations. New Media and Society, 23(7), 2099–2124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444821994490

Elsaesser, C., Patton, D. U., Weinstein, E., Santiago, J., Clarke, A., & Eschmann, R. (2021). Small becomes big, fast: Adolescent perceptions of how social media features escalate online conflict to offline violence. Children and Youth Services Review, 122(August 2020), 105898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105898

Patton, D. U., Eschmann, R. D., Elsaesser, C., & Bocanegra, E. (2016). Sticks, stones and Facebook accounts: What violence outreach workers know about social media and urban-based gang violence in Chicago. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 591–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.052

Cho, H., Li, P., Ngien, A., Tan, M. G., Chen, A., & Nekmat, E. (2023). The bright and dark sides of social media use during COVID-19 lockdown: Contrasting social media effects through social liability vs. social support. Computers in Human Behavior, 146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107795

Lectric eBikes. (2023). We Powered a Village in Zambia with MrBeast! [online] Available at: https://lectricebikes.com/blogs/blog/we-powered-a-village-in-zambia-with-mrbeast [Accessed 12 Mar. 2024].

Overton, I. (2024). Rising toll: London’s teen homicides increase in 2023. [online] AOAV. Available at: https://aoav.org.uk/2024/rising-toll-londons-teen-homicides-increase-in-2023/#:~:text=More%20teenage%20homicides%20were%20recorded [Accessed 12 Mar. 2024].

Figure attributions

Cover image. Depiction of social media platforms, accessed: www.ncsc.gov.uk/guidance/social-media-how-to-use-it-safely

Figure 2, Mr Beast Youtube Millionaire, acessed: www.youtube.com

Figure 3, Protest to end youth violence, accessed: www.4frontproject.org

Leave a Reply