By Suzanne Newcombe

Scholars have increasingly come to recognise that Religious Studies as a discipline is based on the legacies of a colonial worldview, i.e. that what we have classified as religious beliefs and practices have used criteria drawn from white Anglo-European Protestantism. Several members of our department have been leaders in forwarding this discussion within the discipline (e.g. Cotter and Robertson 2016). So, when it came time to design our new second year module here at the Open University, we chose to take a novel approach to Exploring Religions: Places, Practices, Texts and Experiences (A227), first presented in September 2017. Instead of introducing religions from the ‘top down’ – with an emphasis on institutional authority, official beliefs, and structures – we decided as a department to explore religion from be ‘bottom up’ – with an emphasis on what people do, practice and experience as religion (or non-religion) in different specific contexts. In this way, we hoped to challenge what is known as the ‘World Religion Paradigm’ which presents the most popular religious traditions in the world in ‘neat packages’ of the major beliefs, festivals and historical trajectories of institutionalised forms of religion. (A short introduction to our approach to Religious Studies as a subject area is here).

But we also very much wanted our exploration of religion to be enjoyable, accessible, and relatable to our diverse student demographic. So many of our students are facing multiple challenges and demands on their attention while on their study journey. Many are working full-time – and some are studying at full-time intensity as well as having caring responsibilities at home. We also know that a higher-than-average percentage of students on A227 (38% this year) have declared one or more disabilities.

Taken together, these issues raised two key questions for the department:

- What challenges to students and staff may have been created in attempting to create a paradigm shift in understandings of ‘religion’ as a concept (in moving away from ‘World Religions’ towards ‘lived religion’)? How can these challenges be better addressed?

- (2) How can equality, diversity and inclusion be more effectively promoted in the curriculum? What challenges could this potentially pose for staff and students? How can these challenges be better addressed?

To address these questions, we set up a research project, Decolonising Religious Studies. We first interviewed the Associate Lecturers teaching on A227: Exploring Religion, focusing on their impressions of the curriculum and the difficulties that their students reported. Next, we carried out a survey of all students of A227 (17J-20J) in June/July 2021 and held three focus group interviews with nine students in total. We asked them for their impressions of the module, including what we did well, and what we could do better. Finally, we talked with nine colleagues teaching Religious Studies in other UK-based institutions. We asked them, how do you understand Religious Studies as a subject area? What are the subject area’s biggest challenges? What is best practice for teaching and promoting Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) within the subject area?

We are just now starting to analyse the data from this project and will be publishing a full peer-reviewed article exploring the findings in more depth. However, we can give you some initial results of the research and some of the interventions we have already begun to try to improve our students’ experience.

Our Associate Lecturers, many of whom taught on the previous module (A217: Introducing Religions) which was framed more within the World Religions Paradigm, had preferences for familiar ways of teaching and presenting the material. However, they were also coping with adaptation to new technologies with the disruption of all face-to-face teaching during the pandemic. All were working on trying to teach basic essay-writing skills and deal sympathetically with students’ personal challenges as well as teaching the course content. In response, team members Hugh Beattie and Paul-François Tremlett have set up regular online meetings between the Associate Lecturers and Central Academic colleagues to share best practice and new developments in Religious Studies as a field of study.

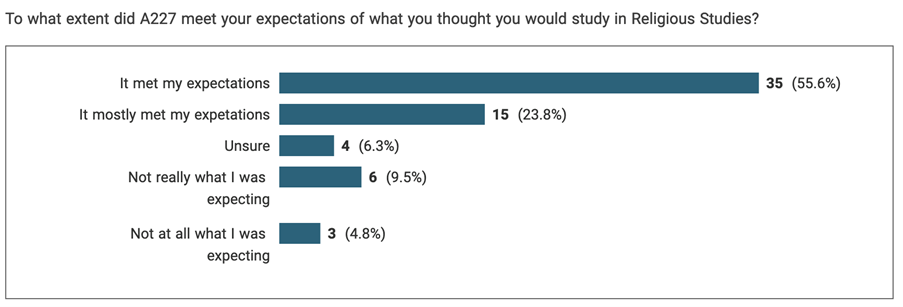

We had a respectable 16% response rate from past and present students who we surveyed about their experience on A227. While most students found that the way the material was structured met their expectations, a significant minority of students didn’t feel that they were taught the content they expected to learn.

To address expectations on A227, the A227 Module Team set up an expectation setting activity in the student forum in advance of the official module start date. In this activity we explained the World Religion Paradigm and why we are taking a different approach. This has significantly increased engagement in the early weeks of the module. Our focus groups also highlighted that there is no discussion of how religions understand disability – or visibility of people with disability – within the A227 material, an oversight that we will take into consideration in drafting new module material.

To address expectations on A227, the A227 Module Team set up an expectation setting activity in the student forum in advance of the official module start date. In this activity we explained the World Religion Paradigm and why we are taking a different approach. This has significantly increased engagement in the early weeks of the module. Our focus groups also highlighted that there is no discussion of how religions understand disability – or visibility of people with disability – within the A227 material, an oversight that we will take into consideration in drafting new module material.

Our interviews with nine external Religious Studies colleagues highlighted that Religious Studies as a subject is intimately bound up with decolonisation and EDI issues. All colleagues saw a need to explain and justify to colleagues and those outside the university environment why a critical study of religion was important. This was often understood in the context of a more general devaluing of the social sciences and humanities in the policy and media environments.

There was a universal concern with best practice in teaching. Many colleagues were doing novel experiments in both teaching and assessment; applying these ideas in the unique environment of the OU will take some thought but is well worth considering. There was also a near-universal acknowledgement that undergraduate students underwent an important period of adjustment in which many aspects of their world are critically examined in a new way. This is a challenging experience that students need to be supported in. The dominant approach was usually a more explicit deconstruction of the world religious paradigm, while teaching within it to begin with at the same time as explaining how the concepts originated in specific historical contexts and have important political implications in the present day. The lived religion or a variety of thematic focuses usually followed this introduction on a structured three-year course specifically in Religious Studies.

We hope that these insights, as well as our further analysis, will help ‘feed forward’ to making both A227 and new material currently being written for the Open University more effective and accessible for all students. Our human beliefs and practices have profound impacts on how we interact with shared global challenges such the climate crisis, the recent pandemic and our positions on war and peace. We want our students to leave our courses feeling more prepared to meet these challenges with confidence in their ability to approach new information and articulate their views in a critical and evidence-based manner.

We wish to thank FASSTEST, the Open University’s Centre for Scholarship and Innovation(@OU_FASSTEST) for their help and support for projects No. 51 and 61 | Project Team: Hugh Beattie, John Maiden, Suzanne Newcombe, Maria Nita and Paul-François Tremlett.

References

Bryan, A. (2016). The sociology classroom as a pedagogical site of discomfort: Difficult knowledge and the emotional dynamics of teaching and learning. Irish Journal of Sociology, 24(1), 7–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0791603516629463

Decoloniality at Contending Modernities @ Notre Dame

Barrett, J (2020) Critical Theory in World Religions: An experiment in Course (re)Design. Implicit Religion 23.3, 218-232. https://doi.org/10.1558/imre.43226

Cotter, Christopher and Robertson, David, eds. (2016). After world religions: Reconstructing Religious Studies. Religion in Culture: Studies in Social Contest and Construction. London: Routledge.

Day, Lee, et al. (eds) (2022) Diversity, Inclusion, and Decolonization: Practical Tools for Improving Teaching, Research, and Scholarship. Bristol University Press.

van Klinken, A. (2020) ‘Studying Religion in the Pluriversity: Decolonial Perspectives’ Religion, 50:1, 148-155, DOI: 10.1080/0048721X.2019.1681108

Lewin, D (2020) Reduction without Reductionism: Re-Imagining Religious Studies and Religious Education. Implicit Religion 23.3, 193–217. https://doi.org/10.1558/imre.43225

Nye, M. (2019) Race and religion: postcolonial formations of power and whiteness. Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 31(3), pp. 210-237. (doi: 10.1163/15700682-12341444)

Nye, M. (2017) Some thoughts on the Decolonization of Religious Studies: postcolonialism, decoloniality, and the cultural study of religion.