Professor Bettina Schmidt (University of Wales, Trinity St. David) gives her opening keynote presentation from our Contemporary Religion in Historial Perspective conference on the 19th Feb, 2018 – “The Contentious Field of the Study of Religious Experience: The Challenging Influence of Rudolf Otto, Andrew Lang and other Founding Fathers.”

Category Archives: contemporary religion in historical perspective

Humour, Concealment and Death Mindfulness in Romanian Funerals

By Maria Nita (University of Wales, Trinity St David)

Death in the West vs. Romanian funeral practices

The modern funeral in the West is increasingly a celebration of life, marked by a depletion of ritual. The French historian Philippe Ariès (1974) claimed that in the West a reduction in the ritual associated with death and dying reflected an inability to accept death caused by the progressive growth in the importance of individuality. Thus ‘the death of the other’ – which was expected and accepted in the Middle Ages as a sort of reintegration in the ancestral community – becomes in modern times, according to Ariès, an unbearable occurrence which can no longer be mediated by ritual. In contrast, the Romanian funeral is still heavily dominated by folk customs, despite some studies suggesting a recent decrease in ritual due to various social factors, such as men taking up a more active role in organising funerals, an area largely considered the domain of older women, who act as expert maintainers of these traditions. (Popescu-Simion, 2014) Also in opposition to the Western emphasis on remembering the past by celebrating the life of the deceased, Romanian funerals are defined by a focused attention on the present, on the moment by moment developments of these rites and also, by an intense relational exchange with the dead body itself. I would like to explore here this engagement with the dead body as a sort of ‘death mindfulness’, leading to an identity transition of the deceased.

Mortu’ as a transitional state in Romanian funeral customs

In Romanian funeral customs, ‘the deceased’ is cautiously talked about as mortu’, a Latin-derived word also meaning ‘the dead body’. ‘Mort’ is, of course, the root word of many English words in this connotative field, such as mortuary, mortality or mortify. Family and friends, all dressed in black, sitting around a traditionally open casket coffin for a three day wake will adopt various attitudes towards mortu’ – from wailing at the head of the coffin, when overcome by grief, to quiet and even jolly conversations, whilst reminding each other to observe all the relevant customs. The customs range from smoky ‘ablutions’ of the body, circling the coffin with frankincense three times a day, to protecting oneself from mortu’ and its potentially dangerous, contaminative and unstipulated rapport with the living: ‘you mustn’t turn your back on mortu’ and if you do, find a small speckle on your clothes and put it on the coffin’, ‘we mustn’t let the candles burn out’, ‘you must put a black scarf on top of the main entrance’, and so on. This could be interpreted as a kind of funeral mindfulness – a practice that focusses one’s attention on the present moment. Towards the end of this process, as the body is taken out of the home or chapel and ‘sent on its last journey’, women rush to cover it with flowers and sometimes jewellery, or even makeup, giving it a puppet-like appearance. The transition is now complete and the frequent relational exchanges of the last few days come to an end.

Humour, death and hidden identities

The ambivalent nature of these interactions seems to have, to some extent, a historical basis. Marina Cap-Bun (2012) shows that in Romanian culture we can identify two concomitant attitudes towards mortality: a pious reverence and abstract idealisation of ‘the departed’ – which Cap-Bun claims to be a later Roman influence, and an older indigenous attitude marked by an irreverent and humorous attitude towards death. This latter is embodied by the Merry Săpânța Cemetery in Romania, which, as the name suggests, abounds in funny and rude portrayals of the deceased. This attitude is also present in old funeral games in which mortu’ was the subject of concealment and trickery; in one extreme example the body was tied up with ropes and used as a puppet to startle unassuming visitors. Like with some shamanic practices dealing with disease, illness and death – laughter and mockery seem to become a gate for plural meanings through which a change or transition of identity is mediated. These polysemic funeral customs are also a constant reminder that one is engaging with mortu’, a transitory and ambivalent ‘being’, in a cocoon-like state. By focussing the attention on the dead body and the present time Romanian funeral rites and customs appear to provide a death mindfulness practice that seems largely forgotten or absent in the West.

Video | The Legacy of Edward Tylor

Over at the Religious Studies Project last week, Graham Harvey and Paul-Francois Tremlett of the OU took part in a roundtable discussion to mark the centenary of the death of Edward Burnett Tylor, one of the seminal figures in the early academic study of religion. This is also the theme for a new volume edited by Tremlett, Harvey and Liam T. Sutherland, ‘Edward Tylor, Religion and Culture’ (Bloomsbury, 2017) which features contributions from all of the roundtable participants (and several other scholars), which was launched at the BASR annual conference in Chester last September.

Edward Burnett Tylor (1832-1917) in many respects has a fixed place in the academic memory of religious studies and cultural anthropology yet acknowledgement of his role is often purely historical, as a key ancestor of little direct relevance to contemporary discussions. This has left us with a limited narrative about the man and his work; a particular received or canonical Tylor defined by his introduction of the concept of animism, his intellectualist approach to religion, his armchair research and staunch social evolutionism. The year of his centenary is an opportunity to begin the task of critically examining the legacy left by Tylor’s work on religion and culture, how much the received Tylor matches his body of work, whether other Tylors can be extracted from these texts which undermine such a limited perspective on a long and eventful career and whether contemporary scholars can find anything of ongoing relevance in the work of such a historically distant figure.

Topics discussed included his impact on indigenous societies, the debates over animism, monotheism and the definition of religion as well as his relevance to the cognitive sciences of religion and the degree to which Tylor can be classed as an ethnographer and more. This roundtable includes contributions from Dr Miguel Astor-Aguilera of Arizona State University, Dr Jonathan Jong of Coventry University’s Brain, Belief, and Behaviour Lab, James L. Cox Professor Emeritus at the University of Edinburgh, Liam T. Sutherland – PhD Candidate at the University of Edinburgh, Professor Graham Harvey and Dr Paul Tremlett at the Open University.

A very ‘Christmassy’ research project!

By Lucinda Murphy, PhD researcher at Durham University

Well, here we find ourselves again in the depths of January; a new year well under way, and the realities of ‘the everyday’ forced back upon us. It feels somehow hard to imagine that, just a month ago, we were all immersed in an utterly different world. It is, as Shakespeare’s Caliban would have it, a world “full of noises, sounds and sweet airs”; a world in which realities are suspended, if not strangely magnified. It’s a world in which time stands still, dreams are indulged and escapist utopias entertained. It’s a world in which no expense is spared; a world of intensity in which expectations press, and emotions run high; a world in which everything seems to have that extra little bit of sparkle; a world which feels just a little bit ‘Christmassy’.

This annual shift into the world of ‘Christmas’ is of course second nature to most of us. Some dread it, some have fun laughing or even complaining about it, whilst others just seem to naively or feignedly ‘wish it could be Christmas every day’. Whichever angle of the spectrum you personally fit into; it seems clear that Christmas is a cultural event, and we might even say, phenomenon which can’t simply be ignored. Quite the contrary; the whole world seems to close down for it. In the UK, as in many other parts of the world during December, it’s pretty much inescapable. It is plastered across billboards, shop fronts and TV adverts; reinforced and cultivated by institutions of industry, public service and leisure; and physically adorned over and around both public and private spaces.

The very hint of even the word ‘Christmas’ conjures up a rich thought-world of symbol and meaning. Father Christmas; mince pies; snowy scenes; peace and goodwill; Christmas crackers; nativity plays; robins; carols; Quality Street; Christmas trees; candlelit churches. Quite clearly, the cultural symbolic resources for the weaving of such ‘webs of significance’ abound (Geertz, 1973). However, as Chris Deacy has recently shown in his 2016 book Christmas as Religion, these various weaves are neither distinctively personal or cultural, nor distinctively religious or secular. At Christmas, perhaps more than at any other time of year, many seem able, or at least willing, to balance multiple identity commitments, multiple emotions, and also multiple parts of their lives into one syncretic community spirited sparkly mixing bowl. And all the while, the perennial search for ‘the true meaning of Christmas’ hovers somewhere in the midst, casting hints of seeming authenticity into a festival which many fear often appears to be losing its ‘magic’ to empty commercialism and the outrageously ‘naff’.

What could be a more fertile window for the exploration of meaning making in Britain today; and more specifically into the complexities of ever-blurring religious and cultural identities? And yet, when I tell people I’m studying for a PhD on ‘Christmas’, I am met more often than not with astonished looks of incredulity. It’s often seen as too frivolous, too ‘fun’ to study (God help academia!). It seems as if this particular cultural world is perhaps a little too close, too special, for many of us to step outside. But it is of course exactly this intimacy that I believe is so worthy of study, and which I have been striving to capture in my ‘Christmassy’ fieldwork over the past few months. What is it exactly about this utopian dream-like world of stockings, magic dust, innocence, truth and fun that seems so personal; and perhaps more pertinently, how does it any of it relate to our ‘everyday’ January lives?

If you think you might be interested in pursuing some of these questions, do join my research assistant @MyElfGelf and I in our Christmassy musings by logging your own Christmas story as part of our online questionnaire, or by following our Festive Log Research adventures at lucindaslog.com or on Twitter or Facebook using #TheFestiveLog.

Religion at the British Museum

By Graham Harvey

Religious objects almost fill the British Museum. In galleries dedicated to Islamic and Asian cultures as well as those related to health and healing there are many artefacts made for religious use. There are large portions of temples from ancient Sumeria, Egypt and Greece. There are deity statues from the Pacific, ancestor masks from Africa and icons from Greece and Russia. A full list would be a long one! And if you search for religious terms in the museum’s website — or in the Google Arts and Culture site related to the BM — the objects displayed are abundant. “Faith”, for instance, appears to be a popular theme for curators and website organisers. This fact indicates more than the presence of objects that originated in religious contexts. It points to the employment of religion as interpretative lens in this putatively secular institution. Two recent additions to the British Museum increase not only the presence of religious objects but also of religious interpretations.

In collaboration with BBC Radio 4 and with a book publisher, the British Museum currently has a temporary exhibition “Living with gods” in its premier gallery, Room 35 beneath the imposing central rotunda. This brings together the 40,000 year old “Lion Man” sculpture from the Stadel Cave, Germany, with recently collected objects such as Jewish kippot (skull caps — one displaying affiliation with a football club), and examples of souvenirs brought home by pilgrims. In between the ancient figure and the contemporary souvenirs are items drawn from across the museum’s collections: e.g. Coptic processional crosses, Hopi kachinas, Islamic prayer rugs, Buddhist icons, a Hindu juggernaut, Zoroastrian and Protestant prayer costumes. Any one of these could generate lengthy discussion — just as they have generated considerable devotion.

For those of us interested in religion as a bodily and material practice, there is something odd about the exhibition. Despite the prevalence of materiality that make ritual acts central to religion, the exhibition is framed and structured by words which insist that religion is defined by believing. Most curiously, the final display board before the exit from Room 35 uses words like “indeterminate”, “ineffable”, “never seen” and “not accessible”. Admittedly, these are said of an (indeterminate) “it” but the presumption must be that they refer to religion, faith, gods and other putatively transcendent realities. Conversations with other visitors to the gallery suggested that I was not alone in finding this an odd conclusion to draw about rich material cultures. Indeed, overheard comments on particular items in the exhibition strongly suggest that at least some objects continue to engage people quite viscerally and directly. Thus, the “Living with gods” exhibition deserves wider attention.

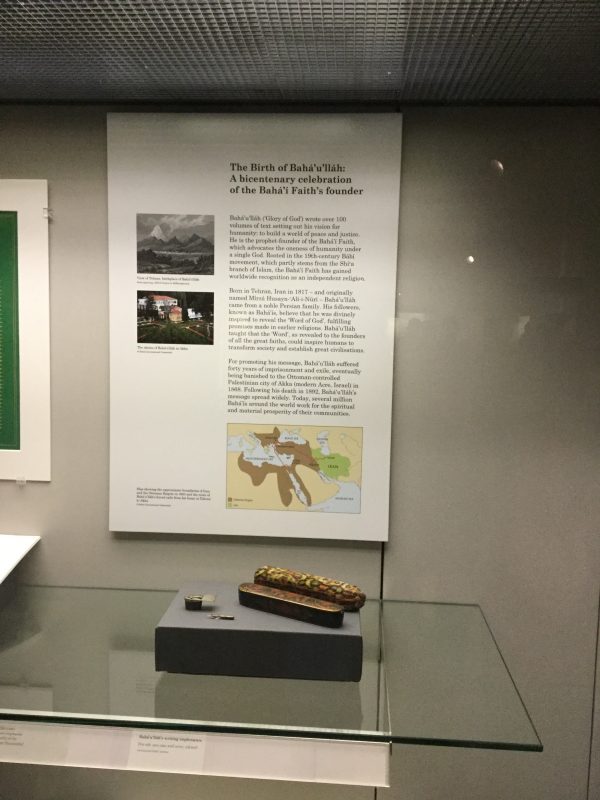

The second addition to the British Museum’s displays is a case commemorating the bicentennial of the birth of Baha’u’llah, the founder of the Baha’i Faith. Along with information about Baha’u’llah, the case contains objects owned by him, such as his glasses and pens, as well as examples of writings considered revelatory by Baha’is. It is placed at the rear of the museum’s Gallery of the Islamic World, devoted to “the cultures of peoples living in lands where the dominant religion is Islam”. The Baha’i Faith has spread worldwide and promotes a vision of global unity. The display case was the focus of considerable attention at a reception hosted in the gallery by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of the United Kingdom. A series of speeches emphasised key themes in Baha’i teachings and celebrated the perception that being able to handle the founder’s pens and correspondence provides an authenticity greater than that of other religions. The positioning, contents and response to this new display provide further encouragements to those of us interested in understanding the presence, practice and politics of religion in the contemporary world.

Identity, Orthodoxy and Ambiguity in Extreme Metal Engagements with Religion

By Owen Coggins

In 2015, an extreme metal band named Batushka appeared, with details about band-members scarce. A deliberately cultivated sense of mystery surrounded their album entitled Litourgiya, featuring a cover which reproduced an orthodox-style icon, heavy on the gold paint (it actually closely resembled another unusual metal album cover, from Advaitic Songs by the band Om, but that’s another story). The music was a gripping combination of pummeling riffs, thunderous percussion and hoarse screeching, but all this guitar distortion and screaming was centred around a chanting of the Russian Orthodox liturgy.

This absorbing combination quickly gathered attention online, and soon enough word had spread to the point that the album has been released in at least twenty different editions on a variety of formats. Soon enough there was an intensive tour schedule, with the stage show including copious amounts of candles, incense in swinging censers, musicians masked and clothed in lavish robes, and an ornately framed painted icon held up at the beginning of the set and then placed reverentially on a lectern. The band’s luminously beautiful website is so rich in religious symbolism you can practically smell it. Of course, the one thing that sells better in the metal underground than great music, is great music shrouded in intrigue and opaque ritual. Two questions continue to be asked about Batushka: what is the identity of the musicians? And what is their religious status?

Metal bands have always, from the earliest origins of the genre in the early 1970s, played ambivalently with the symbols of ritual and religion. Black Sabbath wore large crucifixes on stage and addressed the devil in their eponymous track, while their first album famously featured an inverted cross in the inner gatefold (placed there by designers, as legend has it, unbeknownst to the band). Since then, various bands have combined or contrasted pagan and Christian symbols, played with various versions of Satanism, and expressed all imaginable kinds of religious and anti-religious positions. Participants in metal cultures, as well as external onlookers, have often sought to ask similar kinds of questions: is this music, this band, or this track, anti-Christian? Is it Christian? Is it Satanic? Is it religious?

Understanding Unbelief – understanding what?

By Richard Irvine and Theodoros Kyriakides

In 2013, Nathan Coley’s art installation “A place beyond belief” was brought to Orkney’s shore. The words provoke: what does it mean to be a place beyond belief? One interpretation, enhanced by the juxtaposition of the sign with spire of the redundant church behind it (now Stromness’ Town Hall), is that here is place where church membership, and apparently the relevance of religious belief itself, has declined dramatically. As Steve Bruce has outlined in his book Scottish Gods, the story of the Scottish islands, in keeping with the rest of the UK, has been one of increasing disengagement from organised religion; non-belief emerging as the norm. In this sense, it is becoming a place beyond belief. Yet for those who described the sculpture in its Orkney setting, another interpretation presented itself: here was a place of wonder, a place beyond our limited capacity for belief. A magical place, even.Crucially, the two readings don’t rule one another out. Even as religious belief declines, wonder does not disappear.

This question of what it means to be ‘beyond belief’ is at the heart of the new project we’re starting in OU Religious Studies entitled “Magical thinking in contexts and situations of unbelief”. Our research is part of a bigger, inter-disciplinary project hosted by the University of Kent entitled Understanding Unbelief, and will draw on experiences from our fieldwork in Nicosia, Cyprus (Theodoros Kyriakides) and Orkney (Richard Irvine).

So, what do we mean by unbelief? Our colleagues at Kent have put together a neat glossary of the core concepts for the project of “Understanding Unbelief”, which also provides a definition of the given word. Our objective as anthropologists and ethnographers is, of course, to go beyond definitions. One would be right to exclaim that “unbelief” is a quite vague term and, in such sense, our research does not seek to pinpoint or validate what unbelief is, or where it takes place. Rather, our aim is to use the given term as a springboard, in order to reach a more ethnographically grounded, nuanced understanding of the spectrum of social phenomena which take place in the in-between of large, yet analytically rudimentary, terms such as “unbelief”, “religion”, “belief”, “atheism”, and so on. To try and glimpse what unbelief actually looks like in the messiness of everyday life.

More specifically, our research – *plugplug* – seeks to combine ethnographic literature on magic with emerging studies of atheism and non-religion to explore in what ways magical thinking emerges in the everyday lives of people who, in one way or another, are considered to be unbelievers. Magic is of course a foundational anthropological topic, and the relationship between humanity and magic as whole cannot be understated. For example, anthropologist Lévy-Bruhl used the (problematic) term “primitive mentality” to denote modes of reasoning of ‘tribal’ societies which do not make the distinction between natural and supernatural causality.

Later commentators – such as Stanley Tambiah – point out that the term “primitive mentality” was not intended to describe aspects of thinking specific to non-Western societies but rather a mode of thinking which, under the right social circumstances, can manifest in human consciousness and human action irrespectively of spatiotemporal and historical parameters. Similarly, French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre used the term “magicality” to denote the ability of the human mind to adopt modes of thinking and reasoning which evade the normative social order.

Durkheim, Energy and Contagion

Just published on the blog of Oxford University Press is a piece by Paul-Francois Tremlett taking a fresh look at the work of foundational sociologist, Emilé Durkheim. He argues that we have tended to overlook some of his ideas, and looks at two examples – energy and contagion – from 1912’s The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life:

According to Durkheim, the performance of ritual supplied so-called aboriginal society with the resources it needed to ensure the right balance between the generation of energy on the one hand, and the consumption of energy on the other. Durkheim, of course, could not have known how apposite this line of thought would be to we humans of the Anthropocene, a term coined to mark that moment in Earth’s history when human impact on eco-systems (notably the extraction of resources for generating energy) now threatens the sustainability of all human societies.

You can read the full article here.

Don’t forget that Paul-Francois was also one of the editors (along with our own Graham Harvey and Liam T. Sutherland of the University of Edinburgh) of a recent book which also re-assesses the work of a seminal early figure in the study of religion, Edward Burnett Tylor. Watch out for a video discussion on Tylor in the New Year, recorded at the BASR conference in Chester this September.

Don’t forget that Paul-Francois was also one of the editors (along with our own Graham Harvey and Liam T. Sutherland of the University of Edinburgh) of a recent book which also re-assesses the work of a seminal early figure in the study of religion, Edward Burnett Tylor. Watch out for a video discussion on Tylor in the New Year, recorded at the BASR conference in Chester this September.

Culture Wars 2.0 and the End of Faith

By Paul-Francois Tremlett. Part 1 of a series.

The recent election of Donald Trump to Presidential office in the USA and the referendum to leave the EU in Britain have been described as evidence for an outbreak of new culture wars. The term ‘culture wars’ has been used to describe conflicts in late 19th century England and late 20th century America between secular and religious populations over issues such as gender and sexuality and the status of religious and scientific truth-claims. The rise of the self-styled new atheism was arguably part of the same phenomenon.

Interestingly, the linkage of Trump and Brexit to a new bout of culture wars has no obvious link to any religion-secular flashpoints. The 2016 report by Kirby Swales on the Brexit vote by the National Centre for Social Research concluded that “the EU Referendum was highly divisive, highlighting a wide range of social, geographical and other differences in Great Britain. This was less a traditional left-right battle, and more about identity and values (liberalism vs authoritarianism). It is a strong sign that the so-called ‘culture wars’ of the US have arrived in Great Britain in earnest” (2016: 27). Rich Lowry in The Guardian argued in similar fashion that Trump’s election in the USA exposed new fissures around populism, immigration and nationalism. But, if the new culture wars do not reproduce the religious-secular flash-points of the past, what do they do?

A key feature of the Trump and Brexit election campaigns were claims about fake news and alternative facts. If the arch-postmodernists Jean Baudrillard and Jean-François Lyotard are to be believed, this is because the modern narrative of incremental progress and knowledge is breaking down—if not, indeed, going into reverse. Where classical sociology predicted secularization—a terminal loss of faith in religious institutions—postmodern sociology predicts a loss of faith in all the other institutions as well, from the banks, universities, newspapers and courts to the politicians. The election of Trump and the Brexit vote point to this wider breakdown. The Occupy movement—about which I’ve conducted research in London and Hong and Kong (Tremlett 2012 and 2016)—registered global distrust in economic institutions. The camps that sprang up in cities around the world were attempts to find new sources of authenticity in speech and the face-to-face intimacies of camp life, and to imagine economies not in terms of competition, but rather cooperation. Ultimately, of course, the protests failed both in terms of their primary aim of bringing about political change to rein in the banks and in terms of their secondary aim of restoring peoples trust that they were part of a common society. But the movement did provide an imaginary which formed around the preference for close, horizontal relationships over distant, vertical or hierarchical ones.

The new culture wars, then, may not be about religion, but they are about faith and loss of faith: the loss of faith in existing institutions to speak sincerely and the process of trying to discover something or someone new to place trust in.

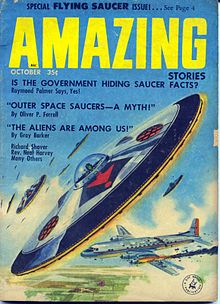

Flying Saucers and Religious Studies

By David G. Robertson

On June 24th, 1947 – seventy years ago on Saturday – Kenneth Arnold was flying his small Cessna over Washington’s Cascade Mountains when saw something odd in the sky. What looked like nine silver crescents could be seen flying in formation at a height and speed the pilot and Deputy Sheriff knew were then impossible. They seemed to move with an odd bobbing movement, which Arnold would later describe as “like a saucer skipping across water” when he reported the sighting. But the phrase was misunderstood by the local press, and soon people all over the US were seeing “flying saucers”. The Roswell Incident, now probably the most famous UFO story, even more so than Arnold’s epoch-making sighting, was reported on July 7th, only thirteen days later.

Thus was born the most lasting and influential new mythology of the modern age.

Thus was born the most lasting and influential new mythology of the modern age.

The UFO narrative has been prominent in the development of new religions since then. Some new religions made UFOs central to their beliefs, such as the Raelians or Heaven’s Gate. In many other cases, UFOs were adopted into already-developed theologies, like in the Nation of Islam. Less obvious, though arguably more influential, was the role they played in late Theosophical thought. Not only were the majority of early contactees Theosophists, but they played a large role in the development of the Findhorn Foundation, and thus the development of the New Age. But here, I want to suggest a couple of more fundamental reasons why UFOs are important for the Study of contemporary religion in historical context. Continue reading