By Niall Oddy

‘We’ve kind of forgotten that what underpins everything is our Judeo-Christian culture, and that’s where we need to start.’ These words emphasising the significance of faith in British society were uttered last month by Nigel Farage, the leader of the political party Reform UK.[i] But is religion really important in Britain? After all, the 2021 census indicated that less the half of the population of England and Wales considered themselves to be Christian and over half of Scottish people declared themselves to have no religion.[ii]

The relationship between religious identity and national identity is contentious. In contrast to Farage’s claim that British identity has ‘Judeo-Christian’ underpinnings, the National Secular Society campaigns to lessen the influence of religion in British society.[iii] Debates about the role of religion in society have a long history, and in this blog post I want to travel back to the sixteenth century, when the Protestant Reformation had unsettled the religious uniformity that had long prevailed in most of western Europe.

The spread of Protestantism forced governments to grapple with how to respond. In England, Henry VIII broke from Rome to establish an independent Church of England. In France, the monarchy remained steadfastly Catholic. Yet, around 10% of France’s population of 15 million converted to the Calvinist branch of Protestantism. Hardline Catholics opposed religious freedoms for this large minority. The monarchy’s attempts to broker compromise failed, leading to over three decades of warfare known as the French Wars of Religion (1562 – 98).

France was not the only country to experience bloodshed as a result of the Reformation. In fact, refugees fleeing religious persecution were so common that the historian Heiko Oberman coined the phrase the ‘Reformation of the Refugees’.[iv] John Calvin was one of over 5,000 French people who fled to the safety of Geneva as the city doubled in size. Basel, Strasbourg and Zurich were also safe places for exiles. As many as 100,000 Protestants from the Low Countries (Netherlands and Belgium) fled to cities in England and the Holy Roman Empire, including London, Cologne, Hamburg, and Frankfurt. Not every Protestant was a refugee, but enough were that exile was a significant and well-known part of Protestant experience, identity and culture. Religious reformers were conscious of belonging to a pan-European community that had suffered persecution and exile from their homeland.

The refugee experience can help us to think about the relationship between religious identity and national identity. What does it mean to have to leave your country of birth because of your religious identity? How does that feel? A travel account by one French Calvinist, Jean de Léry (1536 – 1613), offers some insights.

Born in France, Léry studied in Geneva, became a Calvinist minister and got embroiled in the French Wars of Religion. He was in Sancerre with many fellow Protestants in 1572 when Catholic forces began an eight-month siege that resulted in starvation and acts of cannibalism. Léry survived and eventually settled in Switzerland.

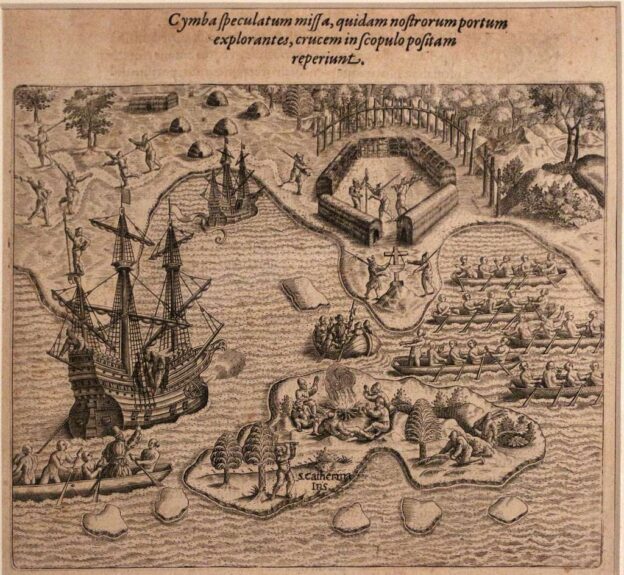

In 1578 Léry published an account of the time he spent in Brazil in 1557 – 58. His History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil recounted how he went with a group of Calvinists to assist with the establishment of a French colony. After some months, disagreements with the Catholics there about religious practices led to Léry and his co-religionists being expelled from the French fort. They spent time living with the indigenous Tupinamba people before returning to France.

In his published account Léry explores his split loyalties to his country and his faith. He calls France ‘my homeland’ and of himself writes, ‘native Frenchman that I am, desirous of the honour of my prince’.[v] Monarchy, though, was problematic from the point of a Calvinist subject to a Catholic king. Writing twenty years after his return from Brazil, and having witnessed the horrors of the Wars of Religion, Léry is nostalgic about his time across the Atlantic and expresses his ‘regret’ that he is not there. For him, Brazil represented a potential safe haven from Catholic France and an opportunity to resolve the contradictions between religion and nationhood:

‘if we had stayed longer in that country, we would have drawn and won some of them to Jesus Christ [and…] there would be at present more than ten thousand Frenchmen who, besides staunchly protecting our island and our fort against the Portuguese […] would now possess under allegiance to our King a great country in the land of Brazil’.

Léry here blames the Catholics for the failure of the colony, expressing a belief that if the Calvinists had not been forced out, he would have been able to perform a service for both his faith and his country.