Tony Keen is a long-time Associate Lecturer for the OU, and an Honorary Associate. This post is based on a talk he gave at the Classical Studies Associate Lecturer Training and Development Day in November 2015.

Tony Keen is a long-time Associate Lecturer for the OU, and an Honorary Associate. This post is based on a talk he gave at the Classical Studies Associate Lecturer Training and Development Day in November 2015.

In the sixteen years I’ve taught for the Open University, I’ve often used movies and television as part of my teaching strategies, and this is just as true for the current module I teach, A330 Myth in the Greek and Roman Worlds. Some of these approaches are obvious – if one wants to talk, for instance, about the Gorgon Medusa, it makes sense to show how the cinema has represented her, in movies such as the 1981 and 2010 versions of Clash of the Titans. Such clips can show students that they actually know something about changing depictions of mythological characters. But it’s also possible to be a bit more imaginative.

mythological characters. But it’s also possible to be a bit more imaginative.

In the collection of Fables attributed to the Greek slave Aesop, there is found an early version of the tale of the town mouse and the country mouse, probably most famous to classicists in the version found in Horace’s Satires 2.6, lines 79-117. The story is simple. A country mouse is invited to dine with his cousin in the town. The town mouse lays out a splendid table, full of gourmet delights that the country mouse simply can never experience at home. But then the party is disrupted by dogs, and the country mouse decides that, for all its simplicity, his home offers security not to be found in the town.

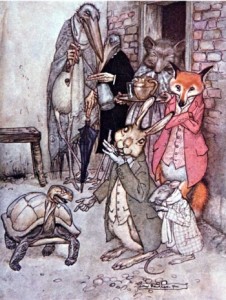

In 1945, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer produced the nineteenth cartoon in their cat-and-mouse series Tom and Jerry, ‘Mouse in Manhattan’, directed by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera. It’s an unusual entry in the run. Instead of the usual mayhem caused by Tom’s unsuccessful attempts to catch Jerry, the premise is that Jerry, bored with life in the  country, sets off for the bright lights of Manhattan, leaving a note for Tom (who is otherwise barely present). The rest is taken up with Jerry’s adventures in New York, and the dangers he faces. There is no town mouse to equate with Jerry’s country mouse, and the existential threat that drives Jerry back to the country is feral cats, rather than dogs. But the fundamentals of the fable are here, and whilst I am not suggesting that Hanna or Barbera had necessarily read Horace or Aesop (they may have, or they may not), they almost certainly had encountered the story in some form. It has, after all, been much repeated through history; Beatrix Potter retold it in The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse, and in 1936 Walt Disney had overseen a Silly Symphonies short called ‘The Country Cousin’, which adapted the fable more faithfully than ‘Mouse in Manhattan’. One effect of showing this to students is to put them in a good frame of mind – who doesn’t enjoy a good Tom and Jerry cartoon? But it also demonstrates how stories are transformed as they are repurposed, and also makes the original fable seem less remote to students.

country, sets off for the bright lights of Manhattan, leaving a note for Tom (who is otherwise barely present). The rest is taken up with Jerry’s adventures in New York, and the dangers he faces. There is no town mouse to equate with Jerry’s country mouse, and the existential threat that drives Jerry back to the country is feral cats, rather than dogs. But the fundamentals of the fable are here, and whilst I am not suggesting that Hanna or Barbera had necessarily read Horace or Aesop (they may have, or they may not), they almost certainly had encountered the story in some form. It has, after all, been much repeated through history; Beatrix Potter retold it in The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse, and in 1936 Walt Disney had overseen a Silly Symphonies short called ‘The Country Cousin’, which adapted the fable more faithfully than ‘Mouse in Manhattan’. One effect of showing this to students is to put them in a good frame of mind – who doesn’t enjoy a good Tom and Jerry cartoon? But it also demonstrates how stories are transformed as they are repurposed, and also makes the original fable seem less remote to students.

Fable is not often dealt with in myth courses. What can  using cinema bring to wider understanding of what is more traditionally understood as ‘mythology’? One issue that can confuse students is that various different versions of myths proliferate through antiquity and beyond. Does Hippolytus die at Troezen, or is he reborn as Virbius in Italy? Who kills Medea’s children, the Corinthians or their mother? I explain this through the modern phenomenon of rebooting screen franchises. There are several screen versions of the superhero Superman, with different versions of when and how Kal-El arrived on Earth from Krypton, and his early life. Similarly, the James Bond movies were rebooted in 2006 with Casino Royale, showing Bond’s first mission as a 00 agent. All previous movies were disregarded, and elements from those, such as the terrorist organization SPECTRE, could later be reintroduced. Cinema audiences cope with this perfectly well, so what is the problem with Euripides’ three incompatible versions of Helen of Troy?

using cinema bring to wider understanding of what is more traditionally understood as ‘mythology’? One issue that can confuse students is that various different versions of myths proliferate through antiquity and beyond. Does Hippolytus die at Troezen, or is he reborn as Virbius in Italy? Who kills Medea’s children, the Corinthians or their mother? I explain this through the modern phenomenon of rebooting screen franchises. There are several screen versions of the superhero Superman, with different versions of when and how Kal-El arrived on Earth from Krypton, and his early life. Similarly, the James Bond movies were rebooted in 2006 with Casino Royale, showing Bond’s first mission as a 00 agent. All previous movies were disregarded, and elements from those, such as the terrorist organization SPECTRE, could later be reintroduced. Cinema audiences cope with this perfectly well, so what is the problem with Euripides’ three incompatible versions of Helen of Troy?

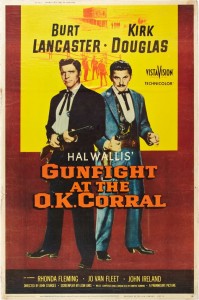

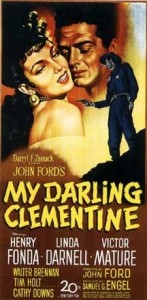

My most unusual use of cinema to teach myth is when I show students two versions of the 1881 Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, in 1946’s My Darling Clementine, and 1957’s Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. I ask the students to note significant differences between the two (for instance, Doc Holliday dies in the gunfight in the former, and survives it in the latter). I then show how the two versions relate to what actually happened, and explain that while the later movie is a little more true to

My most unusual use of cinema to teach myth is when I show students two versions of the 1881 Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, in 1946’s My Darling Clementine, and 1957’s Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. I ask the students to note significant differences between the two (for instance, Doc Holliday dies in the gunfight in the former, and survives it in the latter). I then show how the two versions relate to what actually happened, and explain that while the later movie is a little more true to the events of 1881, nevertheless both fictionalize extensively. My point is to show how fictionalized and mythologized versions of historical events can depart from what actually happened, in different ways in different versions. So it’s almost impossible to use a fictionalized account to reconstruct a putative historical event when historical records don’t exist, and students should be suspicious when that is attempted, as it often is with Homer’s Iliad and the Trojan War.

the events of 1881, nevertheless both fictionalize extensively. My point is to show how fictionalized and mythologized versions of historical events can depart from what actually happened, in different ways in different versions. So it’s almost impossible to use a fictionalized account to reconstruct a putative historical event when historical records don’t exist, and students should be suspicious when that is attempted, as it often is with Homer’s Iliad and the Trojan War.

Hopefully this will spark further ideas of how to use cinema in teaching. Let us know in the comments what you do.

by Tony Keen

Editor’s note: Tony has also produced various Open University learning resources which you can access for free via OpenLearn here.

Paula originally joined the OU in November 1993 and has made an enormous contribution not only to the life of the department, but also Region 13, where she worked as a Staff Tutor. Anyone who has studied or taught on an OU module dealing with the Roman world or Latin language over the last 20 years will be familiar with Paula’s work. She has written at all levels in her time at the OU, often – in true Paula style – choosing to work in close collaboration with central academic and Associate Lecturer colleagues. On the cultural side, she co-wrote A428 (The Roman Family) and the hugely popular material on the Colosseum for A103 (An Introduction to the Humanities), in addition to making distinctive contributions on topics as diverse as Roman reputations (A219 Exploring the Classical World), Roman North Africa (AA309 Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire), Buffy the Vampire Slayer (A330 Myth in the Greek and Roman Worlds) and Seneca (MA in Classical Studies). Her work on our language modules has included chairing Reading Classical Latin (A297) in production – a module that hit the headlines by attracting 1,000 students in its first year.

Paula originally joined the OU in November 1993 and has made an enormous contribution not only to the life of the department, but also Region 13, where she worked as a Staff Tutor. Anyone who has studied or taught on an OU module dealing with the Roman world or Latin language over the last 20 years will be familiar with Paula’s work. She has written at all levels in her time at the OU, often – in true Paula style – choosing to work in close collaboration with central academic and Associate Lecturer colleagues. On the cultural side, she co-wrote A428 (The Roman Family) and the hugely popular material on the Colosseum for A103 (An Introduction to the Humanities), in addition to making distinctive contributions on topics as diverse as Roman reputations (A219 Exploring the Classical World), Roman North Africa (AA309 Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire), Buffy the Vampire Slayer (A330 Myth in the Greek and Roman Worlds) and Seneca (MA in Classical Studies). Her work on our language modules has included chairing Reading Classical Latin (A297) in production – a module that hit the headlines by attracting 1,000 students in its first year. , I’m now approaching the big half century and I’m a freelancer in the aviation industry, having previously served in the RAF. Before joining the OU I had no experience of university level education, having left school at sixteen with a clutch of ‘O’ levels. A trip to Rome reignited my childhood interest in the classical world and I began to read more about it. This was the point at which, with some trepidation, I decided to give the OU a go, over twenty five years since I’d written more than a couple of sentences together, never mind an essay!

, I’m now approaching the big half century and I’m a freelancer in the aviation industry, having previously served in the RAF. Before joining the OU I had no experience of university level education, having left school at sixteen with a clutch of ‘O’ levels. A trip to Rome reignited my childhood interest in the classical world and I began to read more about it. This was the point at which, with some trepidation, I decided to give the OU a go, over twenty five years since I’d written more than a couple of sentences together, never mind an essay!