Julie Bounford, University of East Anglia

The academy and community: seeking authentic voices inside higher education – A workshop on creating and sustaining an engaged research community

On 11th November 2013, I facilitated a small workshop where participants explored some of the essential building blocks for creating and sustaining a research community that cultivates and delivers engaged academic practice. The session focused on features outlined in my research poster. A pdf of the poster, ‘COMMUNI-TEA PARTY AT THE ACADEMY’ can be downloaded – here.

My doctoral research explores ‘community’ as perceived and experienced by twelve individuals who have academic roles at one higher education institution. Individual perspectives and experiences of community and also of university-community engagement are subjective and diverse. However, being connected to or being a part of the university community, the status and strength of those connections and indeed the durability of the community itself appear to be significant for many who are in and around higher education.

When invited to talk about any aspect of community, all decided to focus on the university rather than anywhere else, although they did occasionally refer to experiences of community outside the university. More often, they referred to others who are not formally members of the university but whom they considered to be a part of their research or teaching community. This was evidenced by aspects of their academic practice that could clearly be categorised as community university engagement; for example, collaborating with an expert patient who is acting as a co-investigator in their research project or involving service users in their teaching. All my participants had been involved in community university engagement in some form or other. So, for the purpose of the workshop I asked,

- What makes for an engaged research community?

- Is being connected to or being part of the university community, the status, strength and durability of those connections, vital to engaged academic practice?

- Is ‘community’ actually a good thing, something we should strive for?

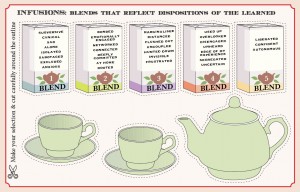

Ron Barnett labelled academic community as a ‘pernicious ideology’, along with entrepreneurialism, competition and quality. He says that it is in its interests to convey the impression that it is a community when its actual dispositions, and indeed, behaviours are quite to the contrary; it can take a pernicious or a virtuous form. The dispositions of my participants varied widely.

I asked the workshop participants if they were surprised by any of these, would they challenge any and is there another blend they would suggest? They referred to the distance between some of the extreme dispositions cited and suggested that there could be another blend for those who feel ‘engaged’. I would agree. For example, if you focused solely on the experience of community in relation to aspects of their day-to-day academic practice and put aside those tricky issues in relation to e.g. the organisation or status, you would find people feeling ‘deeply connected’ and ‘involved’. Another factor discussed in the workshop was that of status, the stage of an individual’s career. My participants included post-doctoral contract researchers, senior lecturers, professors, emeritus professors and someone who had no official status; positions affect dispositions.

Barnett concludes that unlike the other pernicious ideologies, academic community could be turned into a virtuous ideology if effort is put into bringing it about. He refers to the potential of community and individualization working hand in hand, as ‘parallel tracks’ (Barnett 2003 p112). My research may be viewed as a part of that effort to turn academic community into a virtuous ideology, as signified by my own motivation to undertake the research in the first place and by some of my participants who spoke of their desire for a greater sense of community at their institution,

At the broadest level, I am researching the culture of higher education as it relates to idea of community. The impetus for the research came from my professional role as a middle-manager in higher education, responsible for delivering part of a national governmental programme on public engagement which aimed to change the culture of the sector (a programme that has provoked debate and controversy inside and outside the sector). Philosophically, I am committed to the idea of university-community engagement and to the public role of higher education. This is due in part to my professional background and the very reason I came to work in the sector in 2005, in a newly formed role dedicated to managing my institution’s relations with external communities and organisations, primarily in the public and voluntary & community sectors.

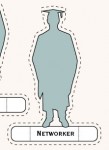

Peter Taylor, who has written about making sense of academic life, suggests that academics have to learn to work with two ‘publics’, the general community and the disciplinary community. They live by two sets of rules. He thinks of academic identity in terms of levels of layers or symbols which reflect the diversity in the meanings attached to the term ‘academic’ (Taylor 1999) . My own research revealed living academic identities wrought by the concrete reality of routines, status, and in particular, relations with and within the university community in its various forms.

I asked the workshop participants if they recognised these roles in relation to themselves and others and if so, when have they been or seen examples, and would more than one apply at any one time? I also asked what roles would they add and are there any that they feel don’t belong here? They commented on the absence of the role of ‘student’ and whilst the roles on the poster were those assigned by my participants to themselves, I would agree that particularly in relation to teaching communities, we should be including the role of student, not as a ‘customer’ or ‘consumer’ but as a member of the teaching community. There is a conversation to be had, I believe, with students, with other university staff (my research involved just academic staff) and with community partners about research and teaching communities, indeed about what the very notion of community means to them.

Sue Clegg describes the university itself as a deeply ambiguous space, referring to pressures and contradictions which both restrict and make possible the living out of personal projects. The university is described as sending out ambiguous messages about what is valued at any particular time, and that espoused and actual values did not seem to match (Clegg 2008 p336).

My research provided a deliberative space in which my participants were able to reflect on that ambiguity, on their relationship with the institution and on their own thoughts about some of the institutional narrative i.e. the university’s Corporate Plan; what it means to them and how it compares with their day-to-day reality of living the university community.

I asked the workshop participants what issues they thought were being raised in these quotes, are they typical and would they expect to hear them in their research community? Or perhaps not; perhaps these are hidden voices. They commented on the diversity of the views expressed. The stories told by my participants when reflecting on their idea and experience of community revealed deeply held values which were only hidden from view if you cared not to look and listen. These values manifested themselves not only in day-to-day academic practice but also in responses to situations when my participants felt challenged. Their academic practice was demonstrated in the following ways:

- They understand how people outside the university may feel

- They try to bring the voice` of the community into the institution, into the university environment through their research

- They engage with those hidden stories and experiences; they knock on the door and ask people what they think

- They invest time and effort into creating and sustaining a learning community by cultivating collaborative practice at a team level

- They nurture individuals, take them by the hand and say what is going to happen, how we’re going to try and make it happen

- They mentor younger colleagues in a non-line management way and are rewarded with a greater understanding of their own academic practice

- They have a strong sense of boundaries and roles. They recognise the need for hierarchies but say that each level must work as it should do

- They get their sense of value and belonging from their engagement and from their research

I was drawn in my research towards the need to find the ‘authentic’ voices in higher education; a need prompted by the sense that in my professional role in the field of community university engagement, where my task was to create the official narrative on community university engagement, I was not altogether hearing them.

Barnett reflected on the possibility of the authentic university. He explored it as a ‘feasible utopia’ but acknowledged that dystopias are never far away. He referred to a ‘dominant self-deceiving mode of being’ whereby a university exhibits ‘bad faith’. For example, when it persuades itself that it can do none other than orient itself towards income generation as its dominant mode of being. Or when the term ‘academic community’ is blithely used to capture a university’s self-image, even though the physicists will have nothing to do with the sociologists, and there is a constant state of tension between the academics and the managers (Barnett 2011 p137).

Barnett also asked whether the university misunderstands the truth about itself or does it understand the truth but blocks it out? He concluded that it is neither one thing nor the other and recognised that authenticity is acted out every day both in tiny occurrences at an individual level and in large activities. This is reflected in the actions of my participants who understand the nature of the institution and of their environment, and who in their different ways demonstrate a ‘feel for the game’ when negotiating their own position and dealing with situations that they are faced with. As Barnett concluded, authenticity becomes possible precisely where authenticity is threatened; it is won in a milieu of inauthenticity.

References

Barnett, R. (2003). Beyond All Reason: Living with Ideology in the University. Buckingham, SRHE and Open University Press.

Barnett, R. (2011). Being a University. London & New York, Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group.

Clegg, S. (2008). “Academic identities under threat?” British Educational Research Journal 34(3): 329-345.

Taylor, P. G. (1999). Making Sense of Academic Life: Academics, Universities and Change, Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Julie Bounford, University of East Anglia

About Julie Bountford

Julie Bounford joined the University of East Anglia (UEA) in 2005, after 19 years in the Public and Voluntary & Community Sectors and has extensive management and partnership experience in homelessness, social policy and criminal justice. Her voluntary work has included the Samaritans, Cambridge Women’s Aid, Norwich Leeway (women’s refuge) and NORCAS (a charity helping people to overcome substance misuse and gambling addition). She is a trustee of ARVAC, the Association for Research in the Voluntary and Community Sector and a member of the Norwich RSA Education Forum. In 2005, Julie instigated UEA’s Annual Community Engagement Survey and in 2007 she co-authored UEA’s successful bid to become a Beacon for Public Engagement and managed the four year Beacon, CUE East, from 2008 to 2012. Julie now works as UEA’s Community University Engagement Manager and is writing up her doctorate on ‘The academy and community: seeking authentic voices inside higher education’. She is a member of the project team for the Arts & Humanities Research Council funded project, ‘UEA Research for Community Heritage Ideas Bank: Realising your idea’ and is a contributing author to Bowater, L & Yeoman, K (2012), ‘Science Communication: a practical guide for scientists’, Wiley-Blackwell.