Seminar given on March 10th, 2014 by Anthony Beck, OrcID: Honorary fellow – University of Leeds, School of Computing

The text is CC0 (+BY). The illustrations are CC-BY.

Improving impact through Open Science

The Detection of Archaeological residues using Remote Sensing Techniques (DART) project has the overall aim of developing analytical methods for identifying heritage features and quantifying gradual changes and dynamics in sensor responses. To examine the complex problem of heritage detection DART has attracted a consortium consisting of 25 key heritage and industry organisations and academic consultants and researchers from the areas of computer vision, geophysics, remote sensing, knowledge engineering and soil science.

Sensor responses to surface and near-surface archaeological features vary under different environmental and land-management conditions. ‘Identification’ and ‘quantification’ concerns the differentiation of archaeological sediments from non-archaeological strata on the basis of remotely detected phenomena (resistivity, apparent dielectric permittivity, crop growth, thermal properties etc). DART is a data rich project: over a 14 month period in-situ soil moisture, soil temperature and weather data were collected at least once an hour, ground based geophysical surveys and spectro-radiometry transects were conducted at least monthly, aerial surveys collecting hyperspectral, LiDAR and traditional oblique and vertical photographs were taken throughout the year and laboratory analyses and tests were conducted on both soil and plant samples. The data archive itself is in the order of terabytes. Although analysis is ongoing there have been a number of methodological and modelling advances that will impact on:

- multi-sensor geophysical and remote sensing approaches

- the relationship of soil moisture, apparent permittivity and temperature variations on signal response in different soils

- the temporal applications of fine spectral resolution active and passive optical sensors

The policy, practice and curation implications of these advances have been examined within the consortium and the broader community.

Open Science is not the same as Open Access

DART has adopted an Open Science philosophy. This has made the consortium critically consider current methods of scientific enquiry and identify how 21st century information and communication technologies can lead to new ways in which scientists conduct, and society engages with, research. The Royal Society discusses these issues in the 2012 publication Science as an open enterprise which states:

Open inquiry is at the heart of the scientific enterprise. Publication of scientific theories – and of the experimental and observational data on which they are based – permits others to identify errors, to support, reject or refine theories and to reuse data for further understanding and knowledge. Science’s powerful capacity for self-correction comes from this openness to scrutiny and challenge.

The Royal Society recognises that ‘open’ enquiry is pivotal for the success of science both in research and in society. This goes beyond open access to publications (referred to as Open Access) by increasing access to data and other research outputs (Open Data) and the process by which data are turned into knowledge (Open Science). The underlying rationale of Open Data is that promoting unfettered access to large amounts of ‘raw’ information enables patterns of re-use and knowledge creation that were previously impossible and/or largely unanticipated. Open Scientists argue that research synergy and serendipity occurs through openly collaborating with other researchers (more eyes/minds looking at the problem). Of great importance is the fact that the scientific process itself is transparent and can be peer reviewed: by exposing data and the data analysis workflows other researchers can replicate and validate techniques. As a consequence collaboration may be enhanced and the boundaries between public, professional and amateur blurred.

The creation of an openly accessible corpus of rich data introduces a range of data-mining and visualization challenges that require multi-disciplinary collaboration across domains (within and outside academia) if their potential is to be realised. The corollary is that knowledge-led policy, practice and engagement can transform communities, practitioners, science and society. An important step towards this is creating frameworks which allow data to be effectively accessed and re-used.

The DART data and other resources (documents, illustrations, scripts, software) are made available through open access mechanisms under liberal licences (Creative Commons by attribution (CC-BY) and Open Database Commons attribution licence (ODC-BY) and are thus accessible to a wide audience via the DART repository at dartportal.leeds.ac.uk. This resource is referenced at a location on the web using a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) which means the resources can be uniquely referenced and accessed. Detailed resource description and discovery metadata have been produced for each resource so that the quality, provenance and re-use potential is fully articulated and effective discovery can occur. The metadata schema has been mapped to other metadata systems Dublin Core, UK AGMAP, and the Archaeology Data Service to facilitate metadata interoperability. The Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH) has been used so the metadata can be openly consumed by third party portals (such as the ADS and Europeana).

Open approaches have challenges that go beyond the technical. DART consortium members had concerns about:

- Timing of resource release – when in the research life-cycle should data be released. This can range from immediately upon capture to never. In some fields publication may be precluded by prior open release. Researchers can be concerned about the loss of competitive advantage, and the impact this may have on career progression.

- Licensing and IP – There is a clear need to examine the impact of licence frameworks and their clauses (by attribution (BY), share alike (SA) and non-commercial) on the data landscape and data re-use. This is particularly important when one considers that more data processing frameworks will be automated and that universities have an interest in protecting IP.

- Access – Who gets access to data, when and under what conditions is a serious ethical issue for the heritage sector. This needs addressing through co-ordinated cross-cutting approach throughout the discipline.

DART instituted its own repository framework. Management and maintenance of a repository is a skilled and time-consuming activity. Funding this through project resources means that there may be problems in maintaining the repository ‘in perpetuity’. It would make financial and logistical sense to host such infrastructure at the institution or national level. This would also address issues associated with trust, provenance and credibility. However, the imposition of financial barriers would have an inevitable impact on uptake.

It is important that these organisational and infrastructure issues are addressed if we are to capitalise on the social and science benefits that open approaches offer. This vision requires co-ordination and can only be built by openly collaborating with other scientists and building on shared data, tools, techniques and infrastructure. For example, knowledge of heritage contrast dynamics is critical for policy makers and curatorial managers to assess both the state and the rate of change in heritage landscapes and helps to address European Landscape Convention (ELC) commitments. In this domain important developments will come from Copernicus (formerly the Global Monitoring for Environment and Security (GMES)) community, particularly from precision agriculture, soil science and well documented data processing frameworks and services. This is enhanced by core benchmarking data collected by projects like DART. What is required is an accessible framework which allows all this data to be integrated, processed and modelled in a timely manner which automatically recognises licence incompatibilities and citation requirements. This vision goes far beyond the ability of DART, and arguably any research project, to deliver but sees the integration or research, practice, policy and public dimensions.

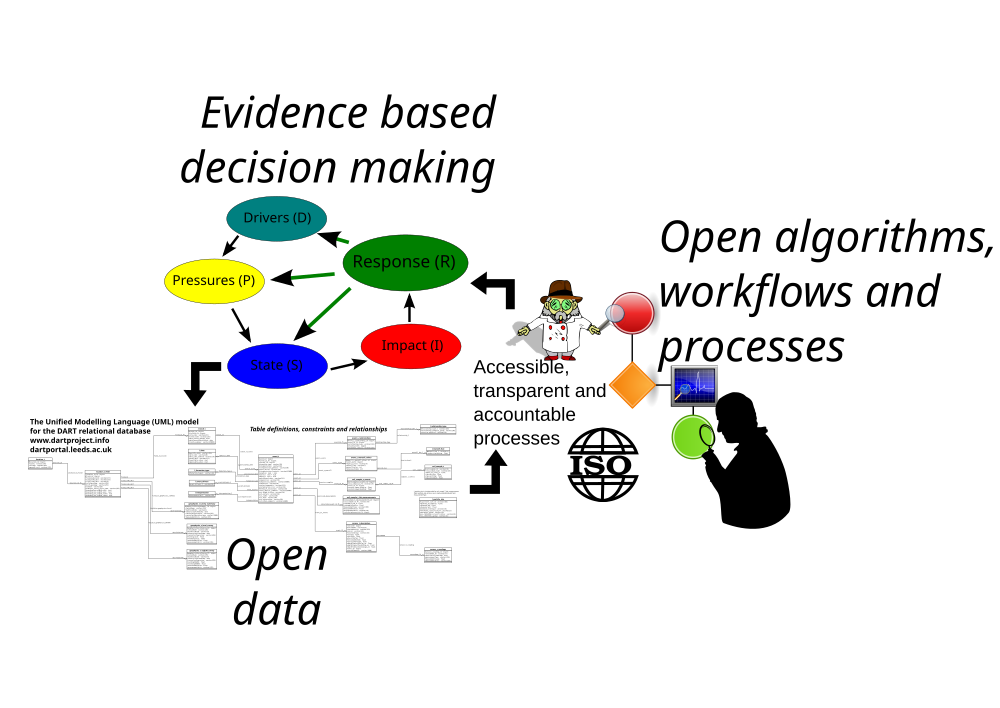

Evidence-based decision-making

The archaeological knowledge base should be, by definition, dynamic: it is predicated on the complex relationship between the corpus of knowledge, theory and classification systems. These relationships are fluid and contain many interlinked dependencies: variations in one constituent part can have complex repercussions. Improved interpretative interplay between theory, practice and data as part of a dynamic knowledge system should empower all communities:

Knowledge is the prerequisite to caring for England’s historic environment. From knowledge flows understanding and from understanding flows an appreciation of value, sound and timely decision-making, and informed and intelligent action. Knowledge enriches enjoyment and underpins the processes of change (English Heritage, 2005. Making the past part of our future).

This work was supported by the AHRC under a Large Programme Grant in the Science and Cultural Heritage Programme, AH/H032673/1.