Over recent weeks the media has been full of women sharing their stories about their experience of sexual harassment, and the statistics are shocking. It’s shocking too, that women, myself included, are not surprised by them. 97% of young women have been the victim of sexual harassment and, over the last decade, a woman has been murdered, on average, every three days. Every day consciously, and unconsciously, women make decisions regarding their safety; what clothing and shoes they will wear and which routes they will take, strategies for regular check-ins with friends, and the ubiquitous carrying of keys between the knuckles. A busy street is a safer street. Talk to women in London, and they are likely to tell you that at night they choose streets filled with moving cars in order to feel safer walking home. Sadly this is no guarantee, as it would seem Sarah Everard was on just such a route when the worst happened. In the wake of the outpouring of grief and anger that another woman had lost her life, the government has pledged to double its ‘Safer Streets’ fund to £45 million, in order to provide better lighting and CCTV coverage to make it safer for women walking through parks and streets, principally after nightfall, although bad things equally happen in daylight as the high profile cases of Rachel Nickell, Suzie Lamplugh and Jill Dando testify. Frustratingly we know that more lighting is not likely to make much of a difference. There is a need for much smarter solutions and savvy urban design to make women’s, (and men’s), movements safer, for both work and play.

On a fundamental level, women need to be directly involved in the design of our urban spaces. Although according to a survey by the Design Council in 2018 only 22% of professional designers are female (disappointing when 63% of all students studying creative art and design courses at university are women and this percentage is significantly higher within further education), the figures are a little more promising when looking at town planning at 41%. Historically most European cities have been designed by men, and, as a result, tend to support their needs which are rooted in a patriarchal system where men travelled to work in defined zones in the city centres. As society and industries have evolved over the past forty years, where people live and work has radically changed leaving historical urban design out of step. It tends not to take account of the day to day activities of modern women, which, on top of now being integral to the national workforce, might include taking children to school or day care, shopping, care for relatives, trips to medical centres, etc. This is amplified by women who work part time in order to support those additional care commitments, and go in, out and across cities at different times of the day and night. Men, of course, have increasingly taken on such responsibilities, but there is a need to fully investigate the differences in how the genders use a city day by day, and how cities can help women feel safe, because at present, in British cities at least, they don’t.

It is frustrating to know that research has been undertaken, but hasn’t necessarily been well supported. In the UK, the Women’s Design Service, (WDS), formed in the mid-80s, published several reports on the changes needed for women to feel safer in the city. The service is currently suspended due to lack of funding. There is also the International Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design Association that looks at the design of cities within the context of their safety. Paul Van Soomeren, one of the board directors has noted how some of the female led research hasn’t been seriously acted upon. However, in Vienna, there have been some particularly successful projects. Opportunities opened up during a period of rapid development after the fall of the Iron Curtain. In 1991, a junior district planner, (now a leading figure in gender mainstreaming in city design), Eva Kail, organised a photographic exhibition entitled ‘Who Owns Public Space – Women’s Everyday Life in the City,’ which documented a day in the lives of eight different women and girls, including a young child, a Turkish housewife, a wheelchair user and an active retiree. A great piece of observational research, it revealed how the city was used in a way that had previously been ignored, demonstrating how, as mentioned above, cities were created in favour of men. Interest in the exhibition prompted debate, and further research was undertaken by the women’s organisation of the governing Social Democratic Party; it corroborated earlier speculation that women moved around cities in a very different way to men. It was found that around two-thirds of car journeys were made by men, while two-thirds of those on foot were made by women.

The following year, Kail was appointed head of Vienna’s first women’s office, the Frauenburo which enabled her to bring more change to the city. As the government implemented a massive new building programme, she noticed that no women had been invited to pitch for any of the contracts thus perpetuating the hegemony of a masculine urban structure. Leading on a social housing project north of the city she made the decision to only invite bids from female architects (at the time, making up just 6% of the profession). The result was a 357-unit complex designed by women to address the needs of the women who would live there, quite literally thinking through the user journey, from going to work, getting off a bus and going into their apartment to make it as convenient and safe as possible. The Women-Work-City, (Frauen-Werk-Stadt, 1997), contained features that are not exactly radical, but they demonstrated care in the thinking that had been absent in previous builds. They offered storage for buggies on every floor, wide stairwells to encourage interaction and a sense of community, and windows that were at the right height to allow residents to see out onto the streets which is something that has long been considered beneficial to keep people feeling safe; ‘the eyes on the street’ (Jacobs, 2020). Day to day needs were catered for; there were attractive green spaces for mothers to take their children outside to play without travelling; public transport was nearby for easy access into work, and there was a nursery, medical centre and commercial spaces on-site.

The Women-Work-City, 1997

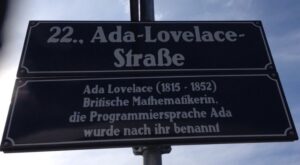

Having seen the success of this early project, Vienna’s city planners were much more open to gender-mainstreaming the wider city and have gone on to implement some 60 projects. The developments make women feel more welcome and even empowered, from smaller measures such as widening pavements so that women with pushchairs or wheelchair users can be comfortably accommodated, to the more symbolic gesture in the vast Aspern Seestadt district, designed to readdress the feeling of male authority and power in cities, where all of the streets have been named after women of note.

A street sign in Aspern Seestadt. Credit: Sian MacLeod, Twitter

A street sign in Aspern Seestadt. Credit: Sian MacLeod, Twitter

Surveys were also conducted to identify areas of anxiety, which led to 26 locations having their lighting improved. Many of the enhancements benefitted all city users, including extra seating that enabled the elderly to feel confident that they could make the journey into the city centre knowing they would have places to rest, and therefore could also stay longer. This has led to a busier shared space that becomes a safer one.

Although women obviously do go out at night in British cities, there are many whose opportunities are limited because they are too anxious to go out after dark. It can affect work, education, and social interaction. To feel intimidated outside in space that belongs to everyone, it sometimes feels as though we, as women, are back at school with the boys dominating the playground. I was thus intrigued to read how Kail had not only looked at how to change the bias of gender dominance in the city itself, she also gave attention to areas where children played to ensure that boys and girls could share the space in an equitable way. This kind of consideration may well have an impact as the children grow into adults, developing a more respectful and integrated expectation of public spaces. Research showed that girls began to use parks significantly less as they went into puberty whereas boys became more assertive users, often for ball games that pushed girls to the sides or away from the parks altogether. A high majority of girls would not attempt to share space that was already occupied by boys, and if they tried, they found they were often spurned with sexual insults or even sexual aggression. A Europe-wide competition was held in 1999 to redesign two parks in the Margareten district of Vienna in consultation with all local users. The designs taken forward included facilities for typically non-gendered sports such as volleyball, roller-blading and badminton, that both girls and boys could enjoy; basketball courts were made more open and fitted with areas for girls to sit and chat, and elsewhere hammocks and sculptural seating were installed for social interaction. Across the parks, lighting was improved and the spaces were more sensitively landscaped. The overall effect was to create a better ‘sense’ of being safe as well as, hopefully, being safer in reality and girls felt happy to use the parks more regularly and to stay there longer. The addition of more seating had a similarly positive effect on elderly users for the reasons mentioned above, and as the number of users went up, including young families, its busyness enhanced its safety for all. The success of this project and further similar developments led to the establishment of gender sensitive guidelines that have been applied to Vienna’s parks since 2005.

Einsiedlerpark, Vienna, one of the two parks redeveloped in the Margareten district.

Given Kail’s belief that to make a city better for women, it needs to be made better for pedestrians, this would bring far wider benefits to all, by reducing pollution and developing tighter, safer, and more self-sufficient communities. We have begun to see the advantages of this kind of lifestyle during lockdowns and finally, some administrations have begun to recognise the potential of this kind of inclusive urban design. We can’t design out psychopathy, but we can design in ways to make life safer and more enjoyable for all.

References

Aspern Seestadt has a female face [Online]: https://www.aspern-seestadt.at/jart/prj3/aspern/data/downloads/DieSeestadtistWEIBLICH_Juli2019_2019-07-09_1607204.pdf [Accessed 15 April 2021].

City of Vienna: Parks: Ways to implement gender mainstreaming [Online]: https://www.wien.gv.at/english/administration/gendermainstreaming/examples/parks.html [Accessed 15 April 2021].

Council of Europe. What is gender mainstreaming? [Online]: https://www.coe.int/en/web/genderequality/what-is-gender-mainstreaming [Accessed 15 April 2021].

Hunt, E., 2019. City with a female face: how modern Vienna was shaped by women [Online]: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/may/14/city-with-a-female-face-how-modern-vienna-was-shaped-by-women [Accessed 15 April 2021].

International Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design Association [Online]: https://www.cpted.net/ [Accessed 15 April 2021].

Jacobs, J., 2020. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. London: Jonathan Cape.

The Design Council, 2018. The Design Economy [Online]: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/asset/document/Design_Economy_2018_exec_summary.pdf [Accessed 15 April 2021].

The Royal Town Planning Institute, 2019. The UK Planning Profession in 2019 [Online]: https://www.rtpi.org.uk/research/2019/june/the-uk-planning-profession-in-2019/#_Toc10127932 [Accessed 15 April 2021].

The Women’s Design Service [Online]: https://www.wds.org.uk/ [Accessed 15 April 2021].

Urban Sustainability Exchange: Gender-sensitive park design [Online]: Available at: https://use.metropolis.org/case-studies/gender-sensitive-park-design#casestudydetail [Accessed 15 April 2021].

Leave a Reply