In the last five centuries, curriculum theorisation has been drawn from platforms laid by Western Eurocentric ontologies and epistemologies, resulting in the duality of knowledge structures (epistemic privilege and epistemic inferiority) known as Cartesian logic. Hence, the central approach to decolonising curriculum involves a critical analysis of how Cartesian duality has shaped what we know, what we recognise and how we reward such knowledge accordingly. Decolonisation is neither about deleting Eurocentric knowledge nor adding diversity; it involves interrogating our ways of knowing, what has been validated by commission, and what has become marginalised and hidden by omission (Arshad 2020). Similarly, Keval (2019) opines that a decolonised approach rebalances the knowledge power and repositions what gets to occupy the centre of ideas and society.

To rethink, rebalance and reposition knowledge power and liberate thought from the fetters of Cartesian duality, Le Grange (2015, 2016, 2020), suggests a 4Rs approach – (i- relational accountability, ii- respectful representation, iii- reciprocal appropriation, and iv- rights and regulation). Relational accountability acknowledges the accountability of the curriculum to all relations while respectful representation is about how the curriculum acknowledges and creates space for various voices and knowledges. Reciprocal appropriation ensures that communities and universities share the benefits of knowledge produced and transmitted. In contrast, rights and regulations ensure that ethical protocols that accord ownership of knowledge are observed.

The ‘Third Space’ as Middle Path in Design Education

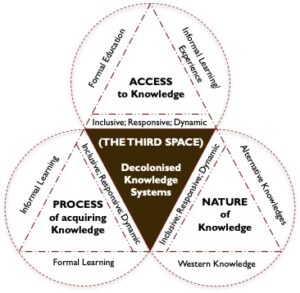

Amidst the different perspectives on decolonisation, the whole concept remains the same, which is to expand our worldview in relation to knowledge by cultivating alternative knowledges that contest the supremacy of one form of knowledge; building relationships, a sense of community, and inclusivity in the pedagogical practices; and promoting and preserving Indigenous culture, which includes languages, practices, knowledges, and history. In other words, cultivating alternative knowledges means creating new systems of thinking, that no longer centres on colonial meaning-making. The shift or new system of thinking, according to Bhabha (2004), is “the Third Space” that draws from the past where necessary but acknowledges that culture is generative and creative. From an epistemological dimension, the concept of expanding worldview focuses on three main aspects, as illustrated in Figure 1: which are i) access to knowledge; ii) the process of acquiring knowledge; and 3) the nature of knowledge.

Figure 1: Decolonised knowledge systems

The process of acquiring knowledge should be dynamic (not static) and go beyond the four walls of formal education. The learning process should accommodate and promote both formal and informal learning, using inclusive learning tools (including language and mode of communication). Approaches such as traditional learning, experiential learning, self-directed learning, open learning, internationalisation, etc. could help create a third space that is conducive to diverse voices and knowledges. Similarly, the access to knowledge needs to be inclusive. For example, developing more structured alternative access to programmes through recognition of prior learning (RPL), where informal learning and experiences can be assessed and considered equivalent to formal learning. Even though RPL has been in place in several universities for a while, the reality is that this pathway to entering higher education programmes remains dormant. Hence, developing a straightforward process and strategy with details of the ontological knowledge on what counts as RPL would enable rather than constrain access to knowledge.

Lastly, the nature of knowledge should contest the supremacy of just one form of knowledge, open spaces to promote a dialogue among others and be responsive to societal needs and the ever-evolving role of designers. A design curriculum content should reflect diverse or multiple perspectives through relational accountability and respectful representation in teaching and learning materials. Examples, case studies, tasks and student projects should reflect potential diversity in the classroom. In terms of inclusivity, it includes not only sociocultural aspects but also socio-economic inclusivity. For example, I have once taught a module (Product design techniques) where the students are from the same cultural background but different socio-economic background. Hence, to ensure inclusivity, I designed the project brief to focus on creativity with minimal financial resources required. In the project brief, I indicated that the cost of developing their design ideas must not exceed a certain amount, and in another project, I asked the students to use only recycled material. This approach is what I see as ‘the third space’ where students don’t feel excluded or inferior just because of their limited financial resources.

As we celebrate Black History Month (October), permit me to reflect on Steve Biko’s writings (I write what I like) about the importance of restoring the dignity of Black people; especially, the negative representation of Black people in history books and the kinds of knowledge disseminated to perpetuate the inferiority complex. According to Biko (1978 92), “the most potent weapon in the hand of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed”. Hence, alternative knowledges and perspectives are critical to restoring the dignity of the colonised character in education and curriculum.

Reference

Arshad, R. (2020). Decolonising and initial teacher education, CERES Blog, September 7, 2020: https://www.ceres.education.ed.ac.uk/2020/08/19/decolonising-and-initial-teacher-education/

Arshad, R. and Bagchi, P. (2021). From inclusion to transformation to decolonisation. Teaching Matters, July 2021. https://www.teaching-matters-blog.ed.ac.uk/from-inclusion-to-transformation-to-decolonisation/

Bhabha, HK. 2004. The Location of Culture. Abingdon: Routledge.

Biko, S. 1978. I write what I like. A. Stubbs, Ed. London: Heinemann.

Keval, H. (2019). Navigating the ‘decolonisation’ process: Avoiding pitfalls and some dos and don’ts. Discovery Society, February 2019. https://archive.discoversociety.org/2019/02/06/navigating-the-decolonising-process-avoiding-pitfalls-and-some-dos-and-donts/

Le Grange, L. 2015. Currere’s active force and the concept of Ubuntu. In: The triennial conference of the International Association for the Advancement of Curriculum Studies (IAACS). University of Ottawa.

Le Grange, L. 2016. Decolonising the university curriculum. South African Journal of Higher Education. 30(2). doi.org/10.20853/30-2-709.

Le Grange, L. 2020. The (Post)human Condition and Decoloniality: Rethinking and Doing Curriculum. Alternation – Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of the Arts and Humanities in Southern Africa. SP31(1). doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2020/sp31a7.

Leave a Reply