My research has always focused on the interactions between the arts, design, science and philosophy, particularly in the later 19th and early 20th centuries. In addition to teaching on the level one design module, U101, I am fortunate to teach on A111 where students examine the impact of the arrival in Europe of artefacts from Benin City, brutally looted during the Punitive Expedition of 1897. Whilst the British struggled to come to terms with the exquisite quality of these items, German curators snapped up many of the best pieces, recognising their value both financially and culturally. Germany was embracing research into ethnology at this time, and was receiving greater governmental investment both for research and acquisitions than it was Britain.

With colonial expansion in the later 19th C there was a natural interest in our human past, bolstered by the scientific theories of Darwin and his associates but also through investigation of other world views. Intriguing artefacts from the colonies inspired artists, designers and academics to explore the spiritual foundations behind them. Some bizarre, complex and troubling theories emerged, and for a significant number of intellectuals, this led them towards the mystic spiritual philosophy founded by Madame H. P. Blavatsky and Colonel Olcott in 1875, known as Theosophy.

In 1910, Wassily Kandinsky published his seminal text Concerning the Spiritual in Art. He had arrived in Germany from Moscow, just before the turn of the century, relinquishing a career in law and economics to train as an artist, but already bringing with him a fascination with ethnography through the shamanistic practices he had encountered in Siberia. His book appeared at a time when many artists were tussling with the relevance of representational art which no longer felt sufficient to express the depth of emotion experienced by creative practitioners as tensions were rising in the west. Order, meditation, and a plunging of the depths to connect with their more peaceful primeval souls, permeated the thoughts of a number of artists and designers emerging from the late 19th century into the fast-changing modern age.

In a previous post, I noted how Charles Rennie Mackintosh, like many other intellectuals of his generation, veered away from the constraints of Christianity to instead embrace a pantheistic world view that seemed to make more sense of the swirl of ideas emerging from developments in science and industry alongside those discoveries of far-flung peoples and their material cultures. Through his theosophical leanings, Mackintosh designed domestic spaces to create a journey upwards to reach a place of spiritual repose, demonstrating his belief in the power of architecture to affect the psyche. His ideas, although generally ignored by the British, were enthusiastically received by German and Viennese designers.

Over in Europe, following the horrors of the first world war, another architect fascinated by ethnography and esoteric philosophies was working on a building that created a rather different ascent into a ‘heavenly’ zone. Whereas Mackintosh’s journey was to a state of love and homeostasis, this architect’s allegiances took a very dark turn. Bernhard Hoetger (1874–1949), through the patronage of the founder of the Kaffee Hag company, Ludwig Roselius, collaborated in creating a building that gave substance to the ethnographic beliefs of Herman Wirth (1885-1981). Roselius was convinced by Wirth’s interpretation of the legend of Atlantis which asserted that the ancient island had been inhabited by Germanic tribes before being submerged in the North Sea. These Germanic tribes, pure Aryans, held wisdom that had spread to Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Native Americans, thereby claiming that Germans were the oldest race. Wirth promoted this legend in his book, ‘The Rise of Humanity’ (1928), a title that immediately suggests its dark influence. Following Germany’s defeat in WW1, there was a drive to establish a strong nationalistic identity, fuelling the Nazi party’s search for evidence of its Aryan ancestry, including the provision of funding for archaeological research.

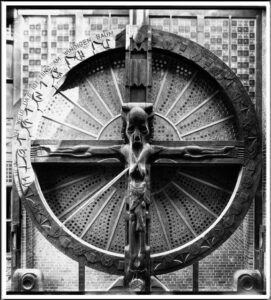

Hoetger’s building, the Haus Atlantis (1929-1931) arose on Böttcherstrasse in Bremen, and was intended specifically as a space for the study of Germany’s ancestral Aryan civilisation. Although now a hotel, some original elements remain open to tourists. Hoetger worked in many arts disciplines, including sculpture. Originally the building carried a huge wooden sculpture, ‘The Tree of Life’, featuring an image of the crucifixion combined with the pagan god, Odin, the ‘Saviour of Atlantis’, symbolising the origins of humanity. It was destroyed by fire during the war.

However, its interior is impressive. A futuristic spiral stairway provides a synaesthetic experience originally transporting visitors up from the cerebral reading room on the first floor, to ascend past vibrant blue panels studded with lights into the spiritual Hall of Heaven (Himmelssaal), a seemingly sacred place designed for dance performances under a stunning arched roof carrying arcane symbols created from blue and transparent glass bricks. With its large bronze disc suspended over what appears to be an altar, it conveys the atmosphere of a mystic cult, linking with contemporary theosophical practices, particularly during a dance performance.

Unlike traditional classical proscenium stage dance venues that supported front facing or profiled choreography, Hoetger’s design offered an unconstrained space that allowed for free expression and observation in the round, ideal for eurythmy, a ‘movement art’ initiated by Rudolf Steiner, founder of anthroposophy, a variant of Theosophy. Even the lights were carefully designed to defuse the beams through mesh rather than use harsh directional stage rigs. In eurythmy, performers bring shape to music or poetry through movement, creating ‘visible language’ or ‘visible song’ amplified through the colours of the flowing garments they wear. They ‘feel’ the music or words through their body, which is then received by those that watch. ‘Movement art’ became very popular within cultural circles in Germany including at the Bauhaus.

In my early twenties, I experienced this myself, as a pianist to a eurythmy group, linked to a Steiner school in Sussex. There was a definite energy present, although I didn’t necessarily find it comfortable. After a number of weeks it was clear that I couldn’t be an adjunct to the group, simply supplying the music, rather, for the sake of the group dynamics, I had to be immersed within it. For me that was a bridge too far!

Hoetger was far from alone in the early 20th century in believing that architecture was a means of expressing societal and spiritual aspirations. Even ‘form follows function’ Louis Sullivan was influenced by religious ideas and believed that architecture could and should be spiritually uplifting. Le Corbusier, although an atheist, likewise worked within a framework where architecture and spirituality were enmeshed as a means of creating social harmony. Using geometry, light, and the physical ‘promenade’ through a building to open terraces, his designs sought to create a sanctuary of purity for the mind, body and soul. Nonetheless, he has also been criticised for alleged links with antisemitism and for having ‘politically ambiguous’ views.

Ultimately, and ironically given its mission, Hitler wanted the Haus Atlantic to be torn down, due to the external sculpture which the Nazi’s hated, and the direction the use of the building was taking. Hoetger was discredited and placed on the list of degenerate artists.

Leave a Reply