The smell of oil and grease evokes happy memories of hours teaching in a secondary school engineering work shop, the clatter of tools and low rumble of machinery, familiar and almost homely – but there is another odour, a whiff of ozone, and this is not year seven last period on a wet Wednesday afternoon.

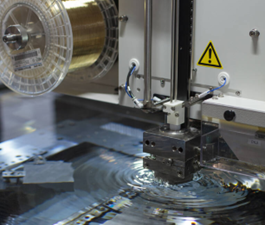

I’m watching an Electric Discharge Wire Cutting Machine slicing its way through a piece of high quality hardened stainless steel – I have seen objects made like this on the internet, clever blocks of metal seemingly cut to perfection, sliding and merging to produce a seamless whole, but this isn’t some trinket or novelty item, this is a valuable block of material being prepared to become part of an injection mould costing well in excess of a hundred thousand pounds. A brass wire carrying hundreds of volts, electrically eroding material across a gap only nanometres wide, while submerged in a bath of dielectric fluid. Whispers of smoke carrying that unmistakable tang of ozone, This is definitely not Wednesday afternoon.

I have been lucky enough to be included in a small group invited by Richard Parker, an Alumni of the Open University and recipient of a Masters of the University, to visit the CGP production facility he owns and runs in Leicester. Although a seemingly small workshop this facility is home to the production of injection moulds not only for simple products you or I might recognise but moulds for parts for life saving medical equipment, top of the range sports cars, and components for both the aviation and aerospace industries.

Back in the office, the tang of ozone is replaced by the smell of fresh coffee and the clatter of the work shop by the hum of computer whirring away on a complex CAD model. We are shown a small yellow and grey sharps bin. An innocuous ubiquitous product, one of the millions of every-day mundane objects that we take for granted. Commonly seen in GPs surgeries, Dentists and A&E cubicles. These smaller models are manufactured somewhere in South Wales, mass-produced in their millions and shipped all over the world. The skill, technology and effort required to manufacture the mould from which it is made however is far from mundane. This level of production requires the skills of a dozen individuals working in design and engineering to produce the intricate complex moulds which are nanometre perfect – just the right angle to click the lock, just enough pressure to lock the lid, just the right combination of design, material and manufacturing to achieve a perfect, simple, functionality, and then to repeat that thousands upon thousands of times to produce millions of the same object to an exacting specification – It is not just making a mould; it is precision engineering, and not just in the shape and form, but the complex cooling channels and variety of attachment points for fluids and ejector pins, it is the careful calculations, the wealth of experience and know how to achieve a mould that will withstand thousands of hours of production.

We find ourselves talking about the nature of design and the intricacies and details of the highly accurate manufacturing process needed to make a mould, but there was another surprise, the need for handmade skilled craftsmanship. Even in this modern environment, to achieve a smooth polished surface were told, that a mould must be hand polished by an expert taking hours of skilled labour. A car headlight mould for example has to be hand polished to a mirror finish and these are so smooth that the finish can cause a vacuum, stopping the part from releasing easily, this seems counter intuitive, that something so smooth would stick but it is this important know how that means Richard and his team are invaluable.

I’m asking about the attachments for the cooling fluids and how the pathways are decided, and again Richard explains that this comes more from experience than any calculation or algorithm. These complex moulds go on to produce thousands of products everyday, but what I am seeing is the space between the designer and the product – the alchemy that takes a design and renders it possible, through skilled tooling, craftsmanship, technology, knowledge and expertise. I realise it is easy to be impressed by marvels of modern engineering, the race cars and rocket ships, but our attention perhaps misses the highly skilled individuals and complex technology needed to produce the essential everyday products. The sharps bin maybe innocuous, ubiquitous, and every-day, but from now on I think I will notice more the amazing talent of the people that bring products like this to life, the unsung heroes of our marvellously modern, mundane world.

Leave a Reply