Harmonising purpose: exploring the ‘Fry Equation’ and bridging the gap between reform and service design by Rachel A.Wood.

Whilst undertaking some literature searches for my design research project, I started to look at significant figures who have worked tirelessly to design, reform, and transform the criminal justice system for mothers in the UK. I was reminded of the work of Elizabeth Fry and started to think about whether she was an early reformer, or an early designer or both.

Through this exploration a prototype ‘Fry Equation’ came into my head as:

Design x Reform = Transform

It was this quote in my reading that started this particular research down this path:

“The confusion and undesigned inaccuracy so often to be observed in conversation, especially in that of uneducated persons, proves that truth needs to be cultivated as a talent, as well as recommended as a virtue” [Elizabeth Fry]

Elizabeth (‘Betsy’) Fry was born in 1780 in Norwich. She has often been referred to as a ‘tireless reformer’ (Anderson, 1995) and someone who challenged traditional gender-based expectations. Such was her legacy that until May 2017 that her image and work with women in prisons was represented on the ‘fry fiver’ (£5 note). Her own mother was a powerful influence on her early life, and inspired her, to advocate for those who had less than they did as a family. It is well documented that she enjoyed the process of writing, and it was after the loss of one of her children (she had 11 in total) that she took to documenting her prison visiting. She seemingly experienced many ‘ups and downs’ in her own life and had her own experiences of poverty more than once throughout her lifetime. She is credited with introducing gender separation in prison settings, and with introducing female wardens.

So, to start this part of my research journey with this my focus was initially on a fascination with the differences and similarities in the definitions of reform and design. These terms are contested, and so for purposes here, these are the definitions that have been applied:

- Prison Reform: “Reduce the use of prison. Improve conditions for prisoners. Promote equality and human rights in the Criminal Justice System” (Prison Reform Trust, 2023)

- Service Design: “Service design is a creative and collaborative practice that determines precisely how an existing service should be improved, or how a new technology or product should be delivered as a service, commercially and at scale” (Engine Service Design, 2023)

A recent study in the criminal justice system argues that the learning and value from a service design project can include both co-design and co-ownership (Armani et. al, 2018, p145):

“….in this case the prisoners were tasked with the challenge of defining the principles to ensure high-level design and were involved not just as another stakeholder but at the heart of the programme, and in a leadership role”.

This inspired me to look at how prison reform, service and co-design concepts could potentially be harmonised in terms of purpose.

What seemed similar in terms of reform and service design was:

🟰Empathy: seek to understand needs, experiences and perspectives of service, and system beneficiaries

🟰Human Centred: emphasise the importance of wellbeing, satisfaction, and preferences of those they are designing, or advocating for

🟰Problem solving: identify challenges, and opportunities to work out potential solutions for positive future change

🟰Research and analysis: recommendations for people, social, economic, or policy related areas to inform and make recommendations

🟰Collaboration and participation: collaborate closely with others and enable participation such as co-design whenever possible. Also influencing and advocating for the change in a positive manner

What seemed different on the other hand:

≠ Focus and context: The goal of service design is to improve the experience for service beneficiaries as well as improve and drive outcomes. The goal of a reformer is to address ‘wicked problems’ in society and improve equity and inclusion.

≠ Scope: For service design this is primarily of services and, or products, and the experiences of them. For reformers this is to bring about policy change, legal reform and shifts in attitudes that affect whole populations or systems (such as the criminal justice system)

≠ Frameworks, tools, and methods: Service designers use the double diamond framework of phases: discovery, define, development and delivery (other alternatives are available!) prioritise customer journey mapping, service blueprints, personas, user stories and experience prototyping. Reformers use legal, regulatory, and policy frameworks. They most commonly utilise skills sets in advocacy, ‘grassroots’ organisation and public awareness campaigns.

≠ Objectives and Key Results (Outcomes and Impact): For service design this always comes back to user friendly, and budget efficient services that meet both beneficiaries and, or organisational or institutional needs. Reformers on the other hand will prioritise social justice, equity and improving lives for those who may experience ‘marginalisation’ or have specific needs.

By this stage gathering such insight had really led me to ponder whether designers can, want and need to switch between these two modes and if so, how, and why?

This was the moment the ‘Fry equation’ (design x reform = transformation) as a prototype emerged to illuminate such issues as:

“I have lately been twice to Newgate to see after the poor prisoners who had poor little infants without clothing, or with very little and I think if you saw how small a piece of bread, they are each allowed a day you would be very sorry” [Elizabeth Fry]

I was also still thinking could, should or must a designer tackle this type of challenge – or can it only be addressed through the lens of reform?

We can of course be certain that Fry didn’t service co-design a customer journey map (as these only emerged as a technique in 1998), or provide a service blueprint (first known use in 1984) – but what things might she have visualised, or documented if she had access to these techniques when she was prison visiting?

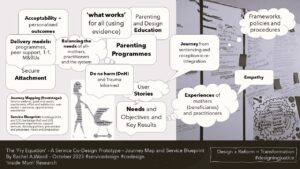

In my updated early prototype of a journey map and service blueprinting of what a future state could potentially be like (based on assumptions as no primary research has taken place yet):

After sentencing and reception, women will receive a holistic needs and outcomes assessment in terms of parenting and education (inc. design). They will receive this from a programme facilitator (inc. those with ‘lived experience’). They will be asked to complete a pre-assessment to assess their journey start (including ‘soft’ outcomes such as by using an outcomes star). They will undertake the prescribed programme – and on attending 80% of the activities will be considered graduated. As part of the programme, they will be invited to take part in co-designing activities that meet needs for their group. This will include parallel design activities that their children can take part in at home, and with other carers, or at school. They will have an allocated peer mentor until they complete the programme (and will undertake a post assessment). They will then be invited to become a peer mentor and attend ongoing design activities as per their own parenting interests. They will be able to continue until they are reintegrated, and facilitators will follow up their ongoing progress for at least 2 years.

It was whilst doing this basic journey map narrative that I came across some research in which design education was delivered in a prison setting. Gamman and Thorpe (2018) propose that design thinking can have a profound impact for such learners. It also looked at the part that co-design can play in this setting, such as through developing their own journey maps, and storyboarding experiences. This made me really reflect and changed a lot of my initial thinking.

Elizabeth’s initial visit to Newgate was in 1813 (not long after she had started prison visiting) in which it was documented that she was particularly upset by the conditions, as she found mothers were often ‘inside’ with their children.

Rose, J. (1980) p87 describes that in visiting she emphasised that she was there to work with the women, and to obtain appropriate consent for any changes. This seems in line with a codesign action research approach, as we know it today. On Fry reading out the twelve proposed rules the women were surprisingly unanimous in their show of hands to accept them.

Some examples of the rules proposed (pp 87-88) as reported were as follows:

- A matron be appointed (rule 1) – someone who Fry herself described as the sort of person who would be a “wise and sympathetic friend” (Fry 1827 in Barton, 2011, p5)

- That the matron would keep an account of the work and conduct of the women (rule 12)

- That monitors and a yard keeper (peers) be chosen to overlook progress and let the women know when their visitors had arrived (rules 4, 6, 7, 8 and 9)

Indeed “when Mrs Fry, read out her rules, each one was voted on separately, by a show of hands”. This technique reminded me of the use of ‘dot voting’ in service design, which has been proposed to be a relational, reflexive approach that focuses on social structures (such as is noted by Vink and Huotari, 2021). Using this has been known to bring about both active prioritisation, and participatory decision making. In this case this would have meant Fry intently listening to the women’s experiences, and then asking them to express what they felt they needed the most to improve their circumstances.

This work had real impact in that it was not only adopted by these women themselves, but also more widely in the prison system and across Europe. These changes included:

- Practical reform in education

- Separation of female prisoners

- Continued advocacy

If Fry had been a service designer today, she would likely have documented what the women had told her in the form of ethnographic user stories. This would be with the view to achieving the best possible future or ideal state for the women, and the system itself. For those unfamiliar with these stories, they are documented in first person in the following format:

As a ….. (type of beneficiary), I want (the goal or activity), so that (the reason)

So, if she had access to this technique as it is now, these are some examples of the stories that could be documented:

- As a parenting programme facilitator, I should have the learning materials for the session available to me, so that I can help mothers have the best possible experience.

- As someone who is a mother, I should be able to access parenting education if I wish or need to, so that I can provide my children with as positive a future as I can

- As a parenting programme facilitator, I must be able to view all the pre-assessments for mothers, so that I can personalise the materials for them as much as possible

- As someone who is a mother, can I have family visits as part of the programme, in a safe and friendly environment?

- As someone who is a mother, can I apply to have a place in a mother and baby unit until my child is 18 months, so that I can develop a secure attachment.

Although such stories have been used for many years in practice terms, they are only more recently appearing in the research literature as a recognised method for capturing needs and requirements (such as Moorman and Young, 2022, Turner et al, 2013, and Gorry and Westbrook, 2011). They could therefore be available to service designers, providers and reformers working in this context to help achieve a required future state.

In bringing the ‘Fry equation’ up to date in this way, my reading led me to Elfleet, 2019, p42 who provides a comparison piece to Elizabeth’s work with 21st Century approaches to gender responsiveness in the form of the Corston Report (2007). The author reflects that, “prison reformers, administrators and politicians, at various points, have all attempted to meet the specific needs of women”. It could therefore be argued that there is still very much an opportunity, or even an imperative for service designers and reformers to work together to respond to needs and experiences of mothers, their children, and the system itself.

Where am I now? So as with all prototypes, my next potential step with the ‘Fry Equation’ will be testing any assumptions and validating them (with other designers, beneficiaries, and reformers). It really has been quite the journey on this so far, and I look forward to the possibility of mapping this out more as part of my future research….

In the meantime, this is a possible for the next iteration:

Design (and research) x Reform = Transformative Systems Change

References:

Anderson, G.M., 1995. Elizabeth Fry (1780-1845): Timeless reformer. America, 173(11), pp.22-23

Armani, J., Mager, B. and De Leon, N., 2018. Service design in criminal justice: A co-production to reduce reoffending. Irish Probation Journal, 15, pp.137-148

Barton, A., 2011. A Woman’s Place: Uncovering maternalistic forms of governance in the 19th Century Reformatory. Family & Community History, 14(2), pp.89-104

Gamman, L. and Thorpe, A., 2018. Makeright—Bags of connection: Teaching design thinking and making in prison to help build empathic and resilient communities. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 4(1), pp.91-110

Gorry, G.A. and Westbrook, R.A., 2011. Can you hear me now? Learning from customer stories. Business horizons, 54(6), pp.575-584.

Fry (1827) cited in Barton, A. (2011:5) ‘A Woman’s Place: Uncovering Maternalistic Forms of Governance in the 19th Century Reformatory’, Family & Community History, Vol. 14 (2), pp. 3-18

Prison Reform Trust (2023) Website page [accessed 09.10.69] https://prisonreformtrust.org.uk/#:~:text=Reduce%20the%20use%20of%20prison,in%20the%20criminal%20justice%20system.

Rose, J. (1980), Elizabeth Fry a Biography, Macmillan, London

Moorman, T. and Young, S.W., 2022. Job Stories: A Creative Tool for Library Service Design and Assessment. The Journal of Creative Library Practice, pp.1-17.

Turner, A.M., Reeder, B., and Ramey, J. (2013), Scenarios, personas, and user stories: User-centered evidence-based design representations of communicable disease investigations, Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 46, (4), pp. 575-584.

Petrillo, M. (2007). The Corston Report: A review of women with particular vulnerabilities in the criminal justice system. Probation Journal, 54(3), pp. 285-287. https://doi.org/10.1177/02645505070540030805

Leave a Reply