A few months ago, I was invited by Kathmandu University as a guest lecturer to run a workshop on Climate Creativity for their final year BA students in Design and Fine Art. The three-week-long workshop was part of their Studio Practice module and through a practice-based approach aimed at generating reflection on the relationship between creative practice and ecological issues in Nepal, especially in and around Kathmandu Valley. While the mountain regions of Nepal are facing an increasing lack of snow and the melting of glaciers, hillside villages are affected by landslides due to unnaturally long monsoons and Kathmandu – still one of the most polluted cities in the world – sees frequent flooding in the summer months.

During our time together, the students and I investigated the impact of climate change on local people and the environment and how national and international designers, artists, and architects have responded to the climate debate.

Students engaged in activities in the studio and nature to explore feelings, emotions and ideas related to the impact of humans on non-humans. They were also encouraged to think locally and reflect on the importance of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), what their ancestors had to say about the relationship between humans and nature through rituals, traditional ways of living in reciprocity with the environment, and storytelling. And we mainly discussed and reflected on the role and tools that this young generation of Nepali creatives may have in reaching their own communities and making complex issues understandable.

From this experience, I found three elements – among others – particularly fascinating and thought-provoking as an educator.

- Students’ interest and enthusiasm – after the initial reluctance – in engaging with nature in an embodied way, in feeling nature. While in most rural areas of Nepal, people still live in a symbiotic relationship with nature, in the city, this connection has gone lost and young generations, either born in Kathmandu or that have moved from rural to urban areas, are losing that feeling of ‘sacredness’ and ‘liveliness’ of nature that protected the environment for millennia. There are no parks or public gardens in Kathmandu, and the built environment has left no space for greenery, to the point that oxygen-producing machines (algae reactors) have been placed in some of the most polluted areas in the city to replace the trees’ oxygen releasing action. However, when students were taken back to nature – the once sacred Bajrabarahi forest at the edge of the valley – they immediately rediscovered – and enjoyed! – that connection. The idea of ‘feeling nature’ became one of their favourite topics in the work that they produced at the end of the workshop and one of the tools that they identified as more powerful to engage local communities in climate debates.

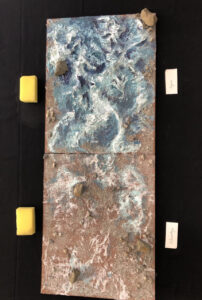

- A strong interest in local climate issues and a struggle to understand problems that are not connected to their territory. For example, students engaged much more with the problems of landslides and flooding and the impact of an over-built environment on nature than the rising sea level or sea pollution. Nepal doesn’t have access to the sea, and travelling abroad for most Nepali people is still impossible or very difficult. None of the students I worked with has ever been to the sea, looked at the sea or swam in the ocean. They said they could understand the problem but ‘didn’t ‘feel it’ and, of course, they wouldn’t be able to communicate it through their own creative practice.

- The rediscovery and creative use of Traditional Ecological Knowledge, especially the meaning of season-related rituals. I asked the students to interview a relative and ask them about at least one agricultural ritual that the older generations used to perform or that they have a memory of. The sharing of the rituals they collected led to interesting conversations about the use of symbols and visual images or objects that are still integrated into their daily life but not recognised or understood. The students thought this could be a way to engage local communities in climate discussion through storytelling and in an inter-generational way. They also believed that their creativity could play a central role in this approach through the production of visual and material artefacts and by incorporating symbols and visual stories into their work. Also, because every ethnic group has its own nature-related rituals – and in Nepal, there are more than 125 ethnic groups – the students felt proud of sharing their own communities’ rituals and were interested in hearing about other ethnicities’ traditions. Some students decided to work on rituals and traditional knowledge for their final piece.

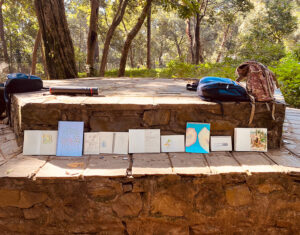

The final open studio was bustling and lively. The students had the chance to discuss the climate issues they decided to focus on and test how their creative skills may engage people, generate interest and foster conversation. For me, it was fascinating to see how traditional ecological knowledge, through rituals and stories, is still alive, powerful and recognisable. It is still there – especially in developing countries – and can generate interest and knowledge. It just needs to be taken back to the surface and shared. It was also interesting to test the depth of an embodied experience with and in nature, how it can connect us to the local environment and how challenging it could be to understand something we haven’t physically and emotionally experienced. We feel, learn and understand through our bodies. As the students said, “We feel for the forest and the river. But if you have never seen or touched the sea, you can understand its problems, but it is more challenging to ‘feel’ for it”.

Leave a Reply