UK Black History Month is drawing to an end and this year, in particular, with all of the events that led to Black Lives Matter protests I have, once again, found myself reflecting on the ethnocentric nature of design teaching. The teaching of design in western culture is based on a narrative of design which is dominated by white, male, star designers. From the Bauhaus to contemporary design the designers whose work is seen to exemplify the highest aspirations of design are drawn from European traditions, the great American designers are enculturated into those traditions. The identification and creation of an individualistic design elite is, perhaps, a discussion for another day. But here in this post I would like to focus on the lack of visibility of black role models in design education.

Nearly two decades ago, as a new module on design and innovation was being put together, I began the search for examples of black designers and innovators and was fortunate to come across a book on black inventors. That book focused on 19th century inventors, people like Elijah McCoy, inventor of a vey popular lubricating can who eventually, in the face of prejudice from other companies, went on to set up one of the first black owned manufacturing companies in the United States. Another, Sarah Goode, an ex-slave is known for inventing a folding bed which doubled as a writing cabinet for people with limited space in their homes.

The 20th century saw more notable black designers such as McKinley Thomson, the first African American car designer who, having won a contest to design a car, won a scholarship to study Automotive Design and went on to work at Ford the year after Rosa Parks took her stand on a bus in Alabama. Thomson worked on some of the most important cars that Ford produced in the 60s. A prolific contemporary of Thomson’s was Charlie Harrison, a product designer who re-designed the Viewmaster toy. From 1961 Harrison designed hundreds of products for Sears, Roebuck and company including a wheeled, polypropylene bin (an early pioneer of bins that are ubiquitous today) and a travelling sewing machine.

Image: amazon

But what of the 21st century and black designers in Britain and Europe? A report by the Design Council in 2018 (The Design Economy), found, surprisingly that the design economy is said to employ a higher proportion of Black and Ethnic Minority people than the wider economy (13% compared to 11%), however, BAME designers are the least likely to be in senior roles, accounting for only 12% of all design managers.

None-the-less, the visibility of black architects, product, fashion and graphic designers remains poor. There are of course some notable exceptions, but, in the 21st century there is still a need for organisations that promote the work of black designers. In the film linked below, Elsie Owusu, founder of the Society of Black Architects talks eloquently about the lack of diversity in her profession and how it does not reflect the diversity of the population.

In fashion there are a few designers who have built their reputations beyond the black community and are more widely known, particularly Joe Casely-Heyford and Ozwald Boateng. More recent black fashion designers who have some media exposure include Grace Wales Bonner, Samuel Ross AKA A Cold Wall and Bianca Saunders

Image: bitsandpcs.com

In graphic design there is Samuel Mensah, founder of Youth Worldwide, an organisation aimed at helping young creatives around the world, to develop their ideas. However, in other areas of design it is far more difficult to find designers of colour. A study by Jomo Tariku, an Ethiopian American industrial designers looked at the collections of 150 of the world’s leading furniture brands and found that just 0.32% of the designs were designed by black designers. (https://www.dezeen.com/2020/07/10/per-cent-black-designers-furniture-jomo-tariku/). This clearly does not reflect global demographics and the potential users of furniture.

An article on a site researching clothing from the African diaspora puts forward some interesting points, firstly, that the number of black students entering design education is disproportionately small, and, secondly, that black designers who come from poor families do not have the resources to promote their work at the big design events such as design fashion week, unlike their richer, white, counterparts (https://ciad.org.uk/directory/where-are-all-the-black-fashion-designers/).

The situation of black people in the UK is complex, although united by the colour of their skin there are many distinct black communities. About half of the black population in the UK come from Caribbean roots (2011Census), from families who emigrated to the ‘mother country’ in search of better prospects and who found a very mixed reception which continues today as the Windrush scandal has demonstrated. The other half of the black population has roots in Africa. Each of the countries in both the Caribbean and Africa has its own distinct culture and design and craft traditions. Although there are some commonalities, black culture is not homogenous. There are different aesthetics and styles just as they are in European cultures. Layered on top of these cultures however, is European design which, through colonisation and subsequent trade relationships between those countries and Europe and the USA, has shaped their cityscapes, fashion and products. There are many far more qualified than I to discuss the need to de-colonise design but in the context of this post suffice it to say there is a growing movement to question the ethnocentric nature of design education and the identification of black designers as ‘other’, based purely on the colour of their skin (https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/what-does-it-mean-to-decolonize-design/).

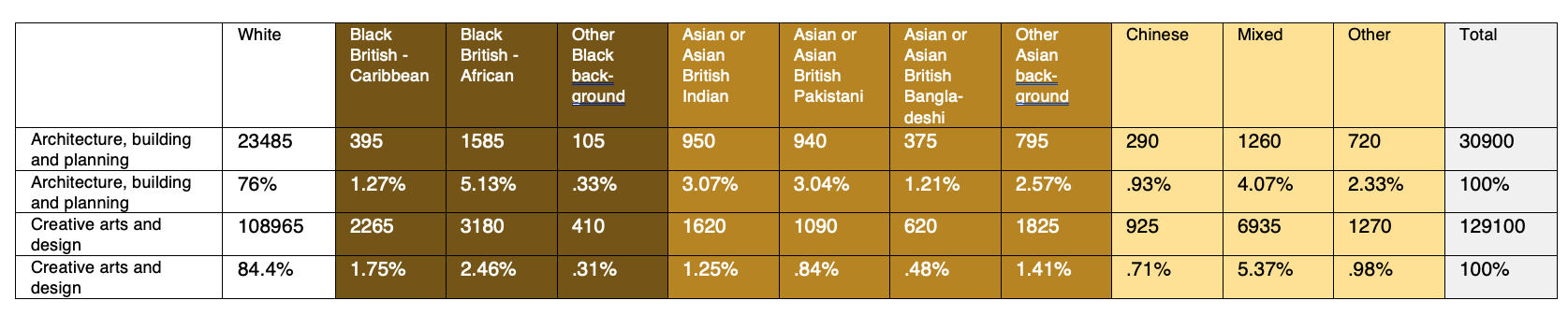

There were over 129000 students studying the creative arts and design in the UK in 2018/19 and over 30000 taking Architecture, building and planning. The chart below shows the numbers of students in each ethnic category in both subjects. What stands out are the relatively low numbers of students identifying as from a black Caribbean background taking design subjects. The figures for students identifying as from a black African background are higher, particularly in Architecture, and perhaps reflect the different circumstances of those communities.

Data: Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA)

So what might we as design educators do to encourage, recognise and celebrate the diversity of the our students’ cultures and experiences? How might we create a truly inclusive curriculum that steps outside the comfortable realms of our own design education and encourages more black students to study design and go on to work in the profession? Firstly, we need to get to know the work of designers from the various black communities both nationally and internationally. We need to be able to tell our students and our potential students, the stories of their journeys and their work so that they might find inspiration and encouragement from them. Secondly, we need to consider the briefs that we set, to ensure that students have the opportunity to communicate and build upon their own cultural backgrounds and experiences in their designing. To do this we need those teaching and marking to be aware of their own prejudices and preconceptions and to enjoy learning and understanding about different cultures. Importantly, we need more black staff so that as white educators, steeped in white design education, we might relearn and rethink our profession.

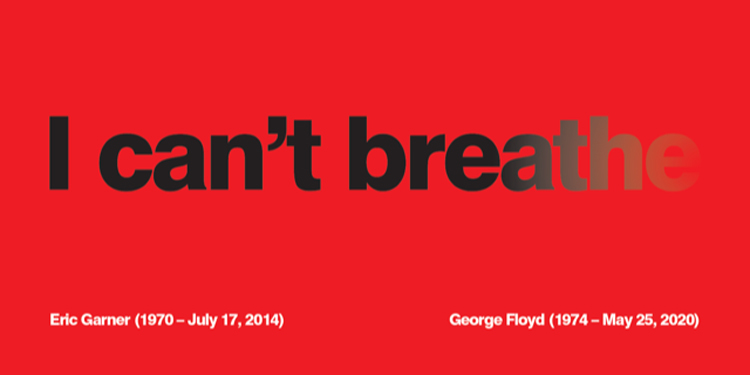

The Black Lives Matter campaign in both the US and UK has harnessed the creative powers of the profession to create memorable images such as Greg Bunbury’s poster. The question is whether this is simply a moment in time or whether, with the support of the cause, it is a seminal moment of change. Are companies truly ready to change and hire a more diverse workforce? Are design education institutions prepared to examine their curriculum and re-imagine the designed world?

Image: Greg Bunbury

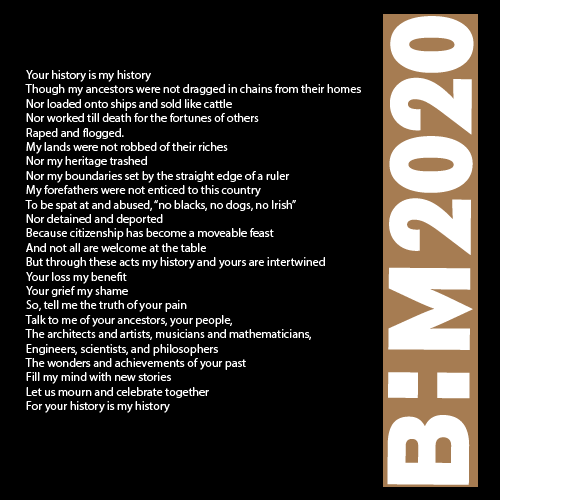

Postscript. For Black History Month the Open University recently held a poetry competition. I have been encouraged to post my entry here.

Leave a Reply