By Marion Bowman

Below the iconic Pulteney Bridge in the centre of Bath there is currently a striking installation, Sinking House by artist Anna Gillespie. As nearby signs explain, ‘Sinking House is a message of warning, and hope, to communities across the world – including leaders gathering at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) – to address the issues, reach for lifelines and act now against the intensifying threat of climate change’. This is just one example of a flurry of contemporary COP26 related creativity I’ve been following in recent weeks.

There will be lots of material culture on display both during and after COP26. I am fascinated by material culture, and what lies behind and goes into the construction of artefacts, for as folklorist Henry Glassie points out, ‘we live in material culture, depend upon it, take it for granted, and realise through it our grandest aspirations’. We make, use, gift, look at and interact with objects to express relationality with other humans (living, dead and future generations), with other-than-human beings, and with the world around us. This is highly relevant as we contemplate what we’ve done to the planet and what needs to be done now.

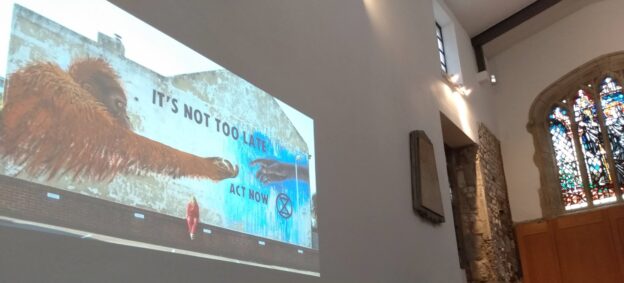

In relation to environmental crises generally, and the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) to be held in Glasgow 31 October–12 November 2021 specifically, numerous artists and other creative practitioners have been ‘materialising’ the global concerns raised by climate change and the need for urgent action. Here I’m drawing attention to just a few of the ways in which increasing numbers of people have become involved in acts of material creative activity of various types, as through material culture they seek to express their concerns, demand change and raise awareness of the pressing issues facing the world. From individual creations to nationwide and international collaborative projects, people are finding ways to provoke thought, and to give expression to their anger, fears and determination. As one crafter put it, it’s about making something to make a difference.

Stormy Seas

STORM by Vision Mechanics, Saturday 2nd Oct 2021, on Storm Walk to Scottish Maritime Museum, Irvine. Photograph courtesy of Scottish Maritime Museum.

Environmental concerns and climate awareness are of course triggered and expressed through a variety of media. The broadcast of the BBC programme Blue Planet II in 2017, highlighting the problem of plastic pollution in the world’s oceans, is credited with an extraordinary rise in environmental awareness and practical responses in relation to the plastic problem; the proprietor of an open-air fruit and vegetable stall in Bath, for example, very directly dates the upsurge in popularity of his business and people’s desire not to have pre-packaged produce to that programme. Such triggers have significant outcomes if they can help move people beyond the despair of what is happening to thinking about practical means through which they can address issues.

A deliberately striking, creative response to the problem of pollution and climate change was the creation of STORM, a ten-metre tall ‘goddess of the sea’ made from recycled materials, the creation of Symon Macintyre/ Vision Mechanics. STORM first appeared for the launch of Scotland’s official year of Coasts and Waters 2020/2021, and after Covid restrictions STORM has been out and about again throughout Scotland, being the focal point in October of a ‘Storm Walk’ from Irvine Beach Park to the Scottish Maritime Museum there, after a ‘Community Clean Up’. Works of art such as this raise awareness and create temporary ‘ambient activism’ in a variety of locations, arresting the attention of both participants and bystanders. The Scottish Maritime Museum is also hosting Climate Change Activism: Protest Posters Workshop for both the 12-15 and 16+ age groups at the end of COP26, to encourage ongoing grass roots creativity and involvement.

Mermaids’ Tears, based on Kurt Jackson’s original artwork, rendered by Louise Trotter in textiles (including string and plastic fibres collected from beaches), on display at Dovecote, Edinburgh, October 2021. Photograph Marion Bowman.

Among many other artistic responses to the plastics problems are artworks by artist Kurt Jackson, who in 2016 produced Mermaids’ Tears, the title referring to an alternative name for nurdles, the tiny plastic pellets which wash up on shores in their billions. Although the original painting was sold as a fundraiser for Surfers Against Sewage (SAS), in 2021 ahead of COP26 Jackson approached the Dovecot Studios in Edinburgh to suggest working with the famous tapestry studio to create a textile rendition of Mermaids’ Tears. This artwork was executed in collaboration with Dovecot weaver Louise Trotter, and forms the focal point of an exhibition running from October 2021 to February 2022 at Dovecote, alongside other awareness raising collage works by Jackson which feature painted sea and beachscapes, with washed up debris incorporated.

However, in addition to the responses of professional artists and craftspersons, the environmental crisis and COP26 have inspired many others to make something to make a difference.

‘Mass-craftivism’ and Crafting Quakers

One undoubted side effect of the Covid 19 lockdowns has been the huge increase in people participating in, rediscovering or taking up craft activities like knitting, sewing, crochet and quilting, as for many the lockdowns opened up time for such pursuits. The Stiches for Survival initiative, for example, describes itself as ‘Mass-craftivism to put the Earth centre-stage at COP26’, a mass participation project whereby assorted crafters are knitting, crocheting, stitching, and crafting in assorted ways panels to make up a 1.5 mile-long ‘scarf’ (representing the 1.5°C target in the Paris Agreement) of climate messages addressed to the COP26 negotiators. After being displayed at Glasgow Green during COP26, the plan is for the scarf to be creatively repurposed into blankets for refugees and other communities who need them, though with some sections being kept for an exhibition and further use in campaigning.

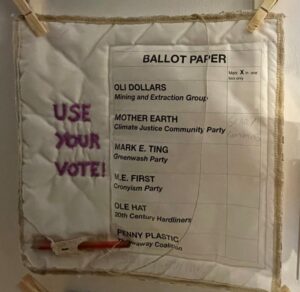

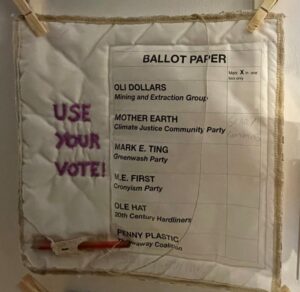

Ballot Paper, textile panel. The Loving Earth Project, Scottish Maritime Museum Dumbarton, October 2021. Photograph Marion Bowman.

The Religious Society of Friends, better known as Quakers, have long been involved in campaigns and practical activism in relation to peace and social justice issues. The Quaker Arts Network’s Loving Earth Project is centred around asking people to address three big questions:

- How does the climate crisis threaten places, people and other things you love?

- What action is needed to reduce the risk of harm?

- How are you helping to make this happen?

Flooded Valleys, textile panels on display at The Loving Earth Project – Scottish Maritime Museum Dumbarton, October 2021. Photograph Marion Bowman.

As the project’s website explains, the idea is to help people engage creatively with these questions, without being overwhelmed, using a range of creative, contemplative and sharing activities. Inviting people to create a 30cm x 30cm textile panel illustrating their responses to these questions, and writing a short account of the panel theme and what actions people are taking personally, has produced enthusiastic, imaginative and visually stimulating responses. Over 400 panels have been sent in already, and many with accompanying texts are displayed on the project website gallery. During COP26 there will be six displays of Loving Earth panels in and around Glasgow, with textile workshops at the larger venues. Over 20 displays of groups of panels have been held already, and more will appear in venues around the UK following COP26 (for information on exhibition venues, see here).

Linda Murgatroyd of the Quaker Arts Network told me:

‘It’s been so exciting and touching to see how the project has been helping people take positive and joyful steps towards greater sustainability. Our online conversations have sometimes been very powerful, especially as we make connections with people in different parts of the world and hear what’s happening there. There are huge issues we all have to face, and so far most of our politicians are reluctant to take the actions recommended by scientists. But everyone can do something if we choose to, though we may need help to work out what.‘

Textile panels on display at The Loving Earth Project – Scottish Maritime Museum Dumbarton, October 2021. Photographs Marion Bowman.

I visited the Loving Earth Project Exhibition which will run until January 2022 at The Scottish Maritime Museum, Dumbarton branch. Explaining her enthusiasm for the project, Nicola Scott, Exhibition and Events Officer, Scottish Maritime Museum, said

‘I was really happy to host the exhibition as I liked that it was a community project. The nature of community projects, although the panels are made individually, is the idea of collaboration and coming together for one purpose. I think this sentiment is very important in terms of climate change and improving the conditions of the environment. The exhibition encourages people to get involved and the additional funding we got from Museum Galleries Scotland allowed us run workshops for people to make their own Loving Earth Project Panel. I know these sessions were important to the Loving Earth Project organisers as the purpose is to let people meditate over the issues of climate change without it overwhelming them and also discuss positive change that can be made with others who attend the sessions. It was a great atmosphere that fostered creativity, discussion and a sense of community.’

Like Stitches for Survival, the Loving Earth Project has encouraged and enabled people to ‘materialise’ a range of emotions and experiences, and in doing so to reflect and discuss with others the major issues to be addressed at COP26 and beyond.

Getting the Message

Lin Patterson’s Quaker Banner, Copenhagen, 2009. Photograph courtesy of Lin Patterson.

A final example of material culture to look out for at COP26 – and one that will be very evident in the next couple of weeks – is the banner. Materially expressing allegiances and protest through banners is a well-established tradition, from religious and trades union processions to Ban the Bomb demonstrations, the Greenham Common Peace Camp and Extinction Rebellion events. My neighbour in Bath, Lin Patterson, is a Quaker and veteran climate activist. She attended the Copenhagen Climate Summit of 2009, for which she made a banner. Intending to be in Glasgow for COP26, and realising that one side was blank, Lin decided to ‘populate’ it further for COP26. Lin made an appeal for messages through the Quaker publication The Friend:

‘This is an invitation to all UK Friends to send brief messages from the heart to be written onto a large, (8 1/2′), Quaker banner going to COP26. This banner was carried in the streets of Copenhagen during the Climate Summit of 2009, with letters infilled with messages from all over the UK. The reverse of the banner shows the same outline letters, but with empty space, awaiting your message for COP26 addressed to leaders, negotiators, and the world.’

Initially concerned that she might not have enough messages to fill the letters, responses came from all over the UK and messages overspilled from the outlines of the letters. The banner was sent off ahead of COP26 to the Quakers in Glasgow, who will be able to use and display it ahead of Lin’s arrival in time for the march on 6 November.

The COP26 side of the Copenhagen 2009 banner, ready for despatch to Glasgow. Photograph Marion Bowman.

As Lin engaged with contributors, she realised that the opportunity to have their message displayed on the banner in Glasgow was both significant and moving. Through their messages, by means of the banner, people were going to be vicariously present at the demonstrations around COP26 – just as the many contributors to Stitches for Survival and the Loving Earth Project will be materially contributing to this momentous event. While banners will be used primarily to protest, send direct messages and express identities at COP26, banners like Lin’s and many of the textile pieces are also using material culture to express relationality with other humans (particularly future generations), with other-than-human beings, and with the world around us.

From ‘citizen crafters’ to professional creatives, the material culture of climate protest, activism and consciousness raising will play an important part in COP26 – and their creators hope they will continue to make a difference in the months and years to come.

Marion Bowman will be in conversation with Lin about her banner and experiences at COP26 during our online conference on 19 November, Eco-creativity 2021: Art, Music, Ritual and Global Climate Politics | Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (open.ac.uk)

Creator: Ted Eytan. Via https://mancunion.com/2021/01/12/opinion-the-republican-party-is-complicit-in-the-attack-on-capitol-hill/. Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Creator: Ted Eytan. Via https://mancunion.com/2021/01/12/opinion-the-republican-party-is-complicit-in-the-attack-on-capitol-hill/. Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0)