By Marion Bowman

It’s the time of year when Nativity scenes appear in a variety of public spaces, homes and churches. Commemorating the Christian narrative of the birth of Jesus, they can vary from the miniature to life-size. The scene is so culturally familiar in Britain, as elsewhere, that it can be both highly stylised and/or be ambiguously or amusingly portrayed (such as Moomins in this shop window display, below) and still be recognisable.

Nativity scenes are examples of religion in the public domain that have become so commonplace as to be almost unremarkable; they are indicative of the sometimes creative, sometimes uneasy negotiation of a Christian tradition that in some respects has become secularised, as well as being observed by people of a variety of religious and cultural heritages. As with many calendar customs, it is not until you look at different national, regional, family and even individual variations and understandings of notionally the same thing that the complexity of such events becomes clearer.

I find contemporary Nativity scenes fascinating on a number of levels, because there is just so much going on in them—and behind them! For me, Nativity scenes combine three of my major academic interests: material religion; vernacular religion, defined by Primiano as ‘religion as it is lived: as humans encounter, understand, interpret and practice it’ (Primiano 1995: 44); and the Bible of the Folk, characterised by Utley as ‘the tales which derive from the Bible and its silences’ (Utley 1945: 1).

St Francis of Assisi is generally credited with the first ‘living’ Nativity Scene, on Christmas Eve 1223 in the Italian city of Greccio, to help people recapture and meditate upon the wonder of the original nativity. The scene was staged in a cave outside and, then as now, was a device to ‘position’ the nativity in a familiar context, making it locally as well as (in Christian terms) universally relevant. Thereafter the Franciscans spread the tradition of creating nativity scenes with live actors and animals. With the development of static nativity scenes came further opportunities for the addition of all sorts of local and contemporary material culture and traditions, and the vernacular expansion of the details of the nativity story.

Nativity scenes have become the visual shorthand for an amalgam of the Christmas story from the Gospels in the Christian New Testament. If you envisage a typical Nativity scene in the UK, what do you see? The usual scene consists of a hut-like building, the stable, with Mary, Joseph and the baby Jesus in a manger, and probably also shepherds, three Kings, assorted animals in the background, and perhaps angels and a star above the stable. They reflect a timeline in which, according to Christian tradition, Joseph and Mary, having to travel away from home and encountering difficulties in finding accommodation at their destination, end up in a stable, where the baby Jesus is born. Angels alert shepherds in nearby fields to a miraculous occurrence, so they come along to the stable to see what’s happening. Eventually some days later three Magi (wise men or, as they later became thought of more popularly, kings) appear bearing gifts, led to the location with the aid of a guiding star. So the typical UK nativity compresses events which occur over a period of time into one simultaneous image (as with the Kimber Farm example above).

In other parts of the world, nativity scenes might be far more elaborate. I remember being amazed by the detail and complexity of Spanish nativity scenes when first encountering a specialist market in Barcelona, selling all sorts of nativity scene requisites beyond simple statues of Mary, Joseph and the baby Jesus. Spanish nativity scenes tend to incorporate a far broader range of side-scenarios in a Bethlehem that looks distinctly local. There are miniature mills with water courses and moving wheels, groups of people gathered round a flickering fire—and somewhere in the scene the Caganer, a bare-bottomed, defecating figure (usually discreetly positioned away from the holy family).

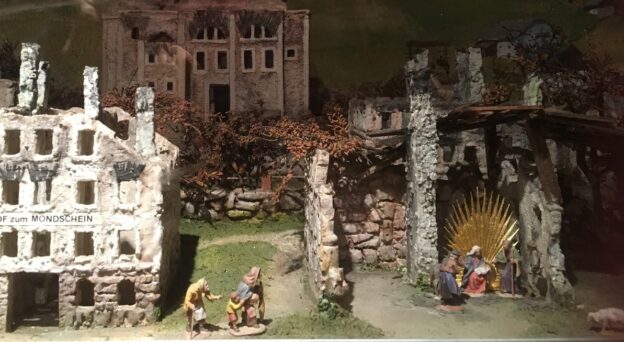

A distinctive Tyrolean style of nativity scenes has developed with scenic backdrops unlike the Holy Land, again self-consciously relating the local to the universal in a manner highly typical of vernacular religiosity. As examples of what is regarded as traditional local craft, scenes in this genre are displayed in the Museum of Tyrolean Regional Heritage in Innsbruck.

In the Krippenausstellun at the Hotel Mondschein in Sexten, a small town in the Dolomites that suffered badly in the first world war (https://www.hotelmondschein.com/krippenausstellung-hotel-mondschein.aspx ), there are various examples of Tirolean scenes. However, one of the most moving examples in this collection is the ‘Christmas 1918’ nativity scene, showing the holy family group alongside the destroyed Hotel Mondschein in the then devastated Sexten. This underlines one of the important pedagogical points being made in Christian terms of the ‘localised’ nativity scene—it places the Christian story wherever its audience is, and though notionally capturing a moment in history, it is also presented as timeless.

Time for Nativity Scenes

Liturgically, Advent is the period ahead of the birth of Jesus, which in the Western Christian calendar can start between 27 November and 3 December; Advent is a time of solemn reflection, and in some traditions is still marked as a period of fasting, similar to Lent before Easter. The celebration of Christmas technically starts with the birth of Jesus and lasts until Epiphany (6 January) when traditionally the three Magi visit Jesus: these are the 12 days of Christmas. Liturgically, however, the Christmas season lasts until 1 February.

An interesting aspect of nativity scenes that I have become increasingly aware of in recent years relates to the logic and logistics of timing. As mentioned, if you think back to the ‘typical’ UK nativity scene and who and what it depicts—Mary, Joseph, Jesus, shepherds, three wise men—it tends to simultaneously compress a narrative that stretches out over a period of time. In the public domain this may not pose a problem, but as we discovered during the fieldwork of the AHRC funded Pilgrimage and England’s Cathedrals: Part and Present (https://www.pilgrimageandcathedrals.ac.uk/about), it can be a point of tension in some cathedral and church contexts (see Coleman, Bowman and Sepp, 2019).

For the project we worked with four partner Cathedrals: Canterbury and Durham Cathedrals, York Minster (Anglican) and Westminster Cathedral (Roman Catholic). At Christmas far more people come to cathedrals and churches generally than at other times of the year, and clearly it expresses for many a sense of belonging. While Cathedrals are happy to receive such visitors, there can be some mismatches in terms of liturgical praxis and more ‘secular’ expectations. Our fieldwork with cathedral clergy, volunteers and other staff around the Christmas period revealed a sense of ambiguity, even ambivalence, over public perceptions of Christmas and how they relate to the wider framework of Advent.

At Canterbury Cathedral we were told ‘The season of Advent is a real hotchpotch because we could do a jolly Carol Service in the afternoon and then at Evensong we’re back into Advent mode, and then there’s another Carol Service for another group’. Similarly, as one informant at York Minster put it, ‘Christmas for the minster begins… with Advent, and is not a full-blown celebration at that time, but a preparation; then when the rest of the world goes back to work, the Minster is in liturgical mode. [We] must recognize that for others, Christmas is over. For the Minster it goes on till Candlemas [2 February]. We are asked why we don’t put lights up earlier and why the nativity is still there “after”.‘

Popular expectations and experiences of Christmas tend to foreground the run up to Christmas as a period of partying and pleasant expectations, as opposed to seeing it as a reflective or indeed penitential period. Although the twelve days of Christmas are referred to in song and on Christmas cards, for many people the Christmas season largely ends with Boxing Day (26 December), actually before the Christmas story has liturgically ended. This can cause some issues in relation to nativity scenes, which our partner Cathedrals handled in different ways. A verger at York Minster explained: ‘The week preceding Christmas we will have put the crib up in the North Transept, but the crib will be empty. And people… come in, see the crib, are puzzled as to why there’s nothing in it, and then we have to explain that actually we’re not at that point yet in the year where we actually have the figures in the crib… the Christ Child doesn’t go into the crib until Christmas Eve.’ Similarly, at Westminster Cathedral, although the nativity scene is likely to be placed on show around mid-December, the baby Jesus figure will not be placed into the crib until 24 December. (We were told that, following an attempted theft, the Jesus figure is now screwed into his crib!)

Meanwhile at Canterbury Cathedral, it has been common to put the baby Jesus figure into the crib as soon as the Nativity scene is set up—a pragmatic response, as explained by one of the canons of the cathedral: ‘In reality we have Jesus in the crib because so many visitors see their visit as an early celebration of Christmas and the baby in the manger illustrates the truth that Jesus was born and died and rose again and is always with us.’

The nativity scene used in Durham Cathedral is indicative of the localising/ vernacular tradition of such scenes already mentioned, containing interesting allusions to the historically locally significant mining industry (see https://www.facebook.com/durhamcathedral/videos/durham-cathedrals-unique-nativity-scene/289019548418700/). Carved by Michael Doyle, a retired pitman, the donkey is a pit pony, the crib is a “choppie box” (in which the ponies were given their feed underground), the innkeeper is dressed as a miner and there’s a whippet in the scene. In the Durham nativity scene, the baby Jesus figure is customarily placed in the crib early on, but is covered by hay until Christmas Eve, when he is removed and then placed back during the Midnight Mass. Volunteers are informed that he must be hidden until the appropriate point of the service. However, in December 2016 our researcher Tiina Sepp spotted the baby Jesus uncovered well before Christmas Eve and mentioned this fact to a steward, leading to a swift restoration of the layer of hay above the statue. The steward’s interpretation was that some parents had wanted to show their children the Baby Jesus and therefore removed the hay from him, again highlighting the differing expectations of visitors and cathedral staff.

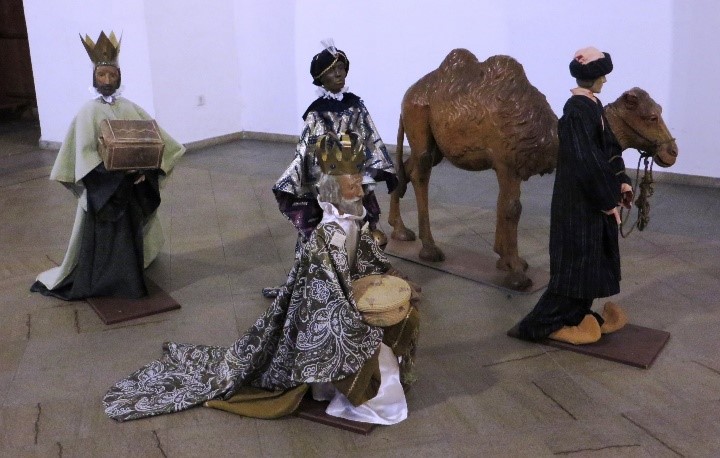

Elsewhere, however, the timeline of the twelve days of Christmas is more closely observed. This was strikingly demonstrated by a visit to Cologne in January 2018, timed to coincide with Epiphany on January 6th, when according to tradition the Magi finally arrived to see Jesus. Cologne Cathedral houses the magnificent Shrine of the Three Kings, said to contain the treasured relics of the Magi. A fine example of Bible of the Folk, from minimal gospel references to ‘Magi’ (Matthew, verses 2: 1-9), usually translated as wise men, the three foreign visitors to the stable gained ‘back stories’, and became popularly designated Kings with the names Melchior (from Persia), Caspar/Gaspar (from India or Tarsus) and Balthazar (designated King of Arabia, sometimes more specifically Ethiopia, and since the 13th century depicted as black).

Through a grille in the beautifully crafted 13th century shrine, three crowned skulls can be seen, above each their name picked out in precious stones. While normally access to the shrine is limited, on 6 January people are allowed to go through the gates and get close to it, which still proves an enormous attraction. Thus, in Cologne there is a very definite sense of the temporal progress of the nativity story, the three kings’ role in it and by extension nativity scenes.

Visiting nativity scenes in various Cologne churches after Christmas but ahead of January 6, we became aware that the Kings were absent. After a while we realised that in some churches there was simply no sign of them, while in others the Kings were to be spotted perched up on the gallery, or out in the church entrance, or gradually moving up within the church as Epiphany approached. It was only on January 6 that the scene was complete, in line with the liturgical calendar. Among other things, this prompts repeated visits to churches to see the nativity scenes as they develop over time!

There is a lot going on behind nativity scenes—from Bible of the Folk embellishments on the gospel accounts of the birth of Jesus, to craft traditions and local pride, from a sense of belonging to evangelising and sometimes uneasy negotiations of secularised assumptions and religion in the public domain. So, as you encounter nativity scenes in this strange year, think about the implications of what you are actually seeing, who is there, what the setting is, what part of the story is being represented—and notice how long they last!

And of course, if you see any interesting examples, please do send them to us at [email protected] and we’ll share them on our Instagram account.

References

Colman, Simon, Marion Bowman and Tiina Sepp. 2019. ‘A Cathedral Is Not Just for Christmas: Civic Christianity in the Multicultural City’ In Pamela E. Klassen and Monique Scheer, eds. The Public Work of Christmas: Difference and Belonging in Multicultural Societies. McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, pp. 240–261.

Primiano, Leonard. 1995. ‘Vernacular Religion and the Search for Method in Religious Folklife’ Western Folklore 54, 37-56

Utley, Francis Lee. 1945. ‘The Bible of the Folk,’ California Folklore Quarterly 4(1), 1-17

It is particularly problematic, I argued, that the ‘early’ Black Majority Churches, those which appeared in the United Kingdom in the decades immediately after Windrush (though thanks to David Killingray and others, we now know something of antecedent congregations in the first half of the century), are largely, if with some notable exceptions, absent in the otherwise booming historiography of secularisation or ‘religious change’ in the 1960s and 1970s. The observations of some contemporary Christian leaders and commentators during the early 1970s were that (as the sociologist Congregationalist pastor Dr Clifford Hill put it in 1971) an ‘urban evangelical explosion’ was underway. These have in some respects been proved right. Without proper discussion of this ‘new nonconformity’ we are left with an incomplete picture of a reconfiguration of the British religious landscape.

It is particularly problematic, I argued, that the ‘early’ Black Majority Churches, those which appeared in the United Kingdom in the decades immediately after Windrush (though thanks to David Killingray and others, we now know something of antecedent congregations in the first half of the century), are largely, if with some notable exceptions, absent in the otherwise booming historiography of secularisation or ‘religious change’ in the 1960s and 1970s. The observations of some contemporary Christian leaders and commentators during the early 1970s were that (as the sociologist Congregationalist pastor Dr Clifford Hill put it in 1971) an ‘urban evangelical explosion’ was underway. These have in some respects been proved right. Without proper discussion of this ‘new nonconformity’ we are left with an incomplete picture of a reconfiguration of the British religious landscape.