Money is so ubiquitous, so ordinary and everyday that it can sometimes evade critical scrutiny. We are familiar with using money as a means of exchange; we are paid money for our labour, and we pay or owe money for the goods and services that we use or purchase. Money is a magic that renders very different things equivalent by assigning them values. These days we are inundated with news about the cost of living and the economy, but I am not talking about money in this sense, or indeed as a kind of magic. The money I’m interested in is the physical stuff in our pockets, purses and wallets and, in particular, the national and cultural symbols that it carries.

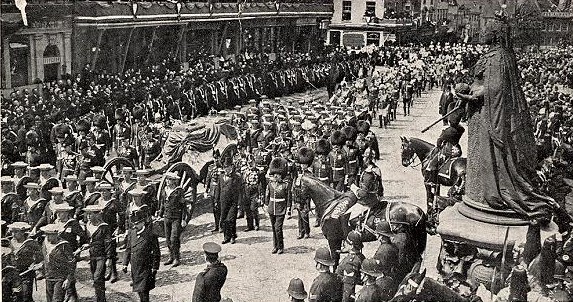

If you have some coins and notes to hand, this would be a good moment to examine them: in my wallet I have one ten-pound note and one twenty-pound note. On the ten-pound note there is the Queen (I’ve yet to see one of the new notes displaying the King’s head) and various images associated with Jane Austen including a quote from Pride and Prejudice and images of Godmersham Park which Austen visited a number of times, as well as Winchester Cathedral, where she was buried. On the twenty-pound note there is the Queen (again), and the painter J. M. W. Turner and an image of his painting, The Fighting Temeraire. I also have some coins of various values which are notable for carrying various national and cultural symbols including the Queen’s head, the Royal Coat of Arms and the phrase “Dieu et Mon Droit” which refers to the divine right of the monarch and the national symbols of England (rose), Scotland (thistle), Wales (leek) and Northern Ireland (shamrock). The point I am making is that when we use physical money, we are not only exchanging these tokens (coins and notes) for goods and services. We are also exchanging culturally loaded national symbols which, among other things, authorise the works of certain individuals as exemplary national culture and legitimate certain institutions as sacred.

But what has any of this got to do with secularization? The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions (2000) defines secularization as that process whereby “people, losing confidence in other-worldly or supernatural accounts of the cosmos and its destiny, abandon religious beliefs and practices” such that “religion loses its influence on society”. But we can also understand secularization as a wider process that is not only about religion but about the wider desacralization – or what the sociologist Max Weber called “disenchantment” – of once hallowed beliefs, practices and institutions.

One of the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic has been the rapid decline in the exchange of the physical tokens called money and their replacement by contactless and online methods of exchange. According to Bella Thorpe-Woods, before Covid, the exchange of cash had been dropping by around 15% a year since 2017 (source). In 2020, partly as a result of (erroneous) fears that Covid could be caught by handling notes and coins, that fell by a further 35%. Current projections suggest that Britain will be a cashless society by 2026.