Through 2020, as QAnon promised to destabilise the US democratic process, and anti-vaxxers threatened to perpetuate a global pandemic, theories about an older conspiracy were quietly playing out by the banks of Loch Ness in the Highlands of Scotland. Boleskine House, the former home of Aleister Crowley and later, Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin, has been approved for restoration which will see it being opened to the public for tours, with ten eco-cabins built on the grounds for guests. Or rather, its shell has. Boleskine House was badly damaged by an accidental fire in December 2015, losing most of the interior. When I visited the site in 2016, it was fenced off and full of rubble. It was put up for sale in April 2019, and was bought by Keith and Kyra Readdy, who founded the Boleskine House Foundation to raise the money needed to restore the site. But a second fire broke out on July 31st, 2019, destroyed the remainder of the interior, and claimed the roof. The fire brigade investigated the second fire as arson.

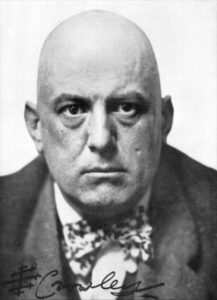

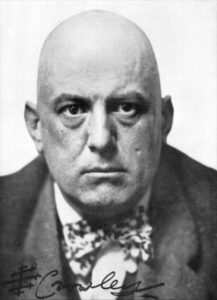

As someone who grew up in Inverness during the time that Page owned the property, the story has a particular fascination for me. But as a scholar of contemporary religion in historical perspective, the most interesting aspect is how it shows that ideas about “Satanists” still have currency in the modern age. Boleskine House is famous as the former home of Aleister

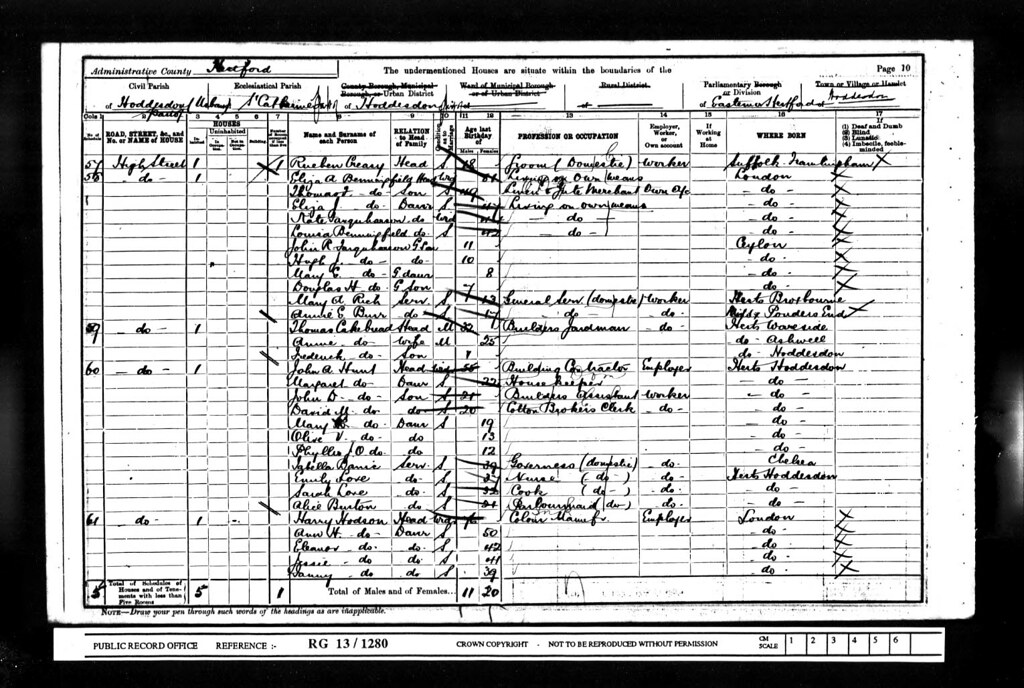

Crowley, who owned it between 1899 and 1913. Crowley had impressive careers as a mountaineer and poet, but it is for his writing on the occult that he is most famous today – he was a prodigious innovator and systematiser of different magical systems and incorporating Egyptian deities and yoga techniques into his practices. He received a series of channelled communications in 1904, and years later these would form the basis of his esoteric religion, Thelema. In the popular imagination, however, Crowley is remembered for the “Wickedest Man in the World” epithet that he gained as a result of a court case, in which he was branded a “Black Magician” and a sexual reprobate. This had more to do with the homophobia of the Edwardian period than reality, however, exacerbated by his adoption as a figurehead of the sex and drugs culture of the 1960s, including the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin. Crowley was certainly an egotist, and could be cruel, but a more sober assessment of his life would have to also count him as one of the most important figures in the history of twentieth century new religions, directly influencing the development of Wicca, Scientology and Discordianism, as well as founding Thelema and leading the Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO).

At the beginning of December 2020, Councillors on the South Area Planning Committee approved the proposals, despite resorts of “a number of objections” from locals. In addition, Councillor Margaret Davidson is quoted as saying: “Over the years it has been a place people have visited and become obsessed with the area… That has caused its own difficulties for people in Foyers and Inverfarigaig, the nearest villages, and I would wish that to stop for them.” But the chairman of the committee concluded that “matters associated with previous ownership of the property… are not material in planning matters.” I was pleased that the local Council approved the application, because although Inverness is a pretty liberal and secular place, there are certainly still pockets of Lutheran conservatism in the Highlands. The more traditional Conservative press picked up on the story, even as global pandemics, Brexit and a climate crisis all reached a head, showing there is still a deep-seated fear of the occult.

Take this article which appeared in December in the Herald. It is relatively sober, at first glance – even if it does claim that Crowley “became known as ‘the real-life Wicker Man’”, which makes little sense on any level. But a closer reading shows that it is embedded in a worldview in which Christian forces of light are battling an occult, even Satanic, darkness. It states that Crowley “conducted various black magic rituals at the house including a six-month long experiment to raise his Guardian Angel. It is said the experiment was not properly completed, with the spirits raised never fully banished leading to a number of unexplained events at Boleskine.” Such a story only makes sense if you are in a universe in which there is in fact magic, and also spirits which can be raised by (ab)using it.

More sensational was the story originally in the Inverness Courier, and later picked up by the Daily Mail (as well as others) under the headline “Plans to build holiday lodges close to fire-ravaged Loch Ness house of Aleister Crowley spark fears area will become a shrine for SATANISTS visiting home of ‘world’s wickedest man’ who inspired some of Rock n’ Roll’s darkest music.” It cites “objectors”, but only two are ever named in multiple news stories. One, Naomi King, stated that “the place will become a major Satanic temple and a hub for Satanist abusers from across the world to visit”. This is nonsense, as Crowley was never a Satanist, nor are any of the organisations identified in the reports, such as the OTO (Ordo Templi Orientis), which is not a “secret society” either. Interestingly, the article also mentions (conspiratorially) that King “claims her comments on the council’s planning portal had been ‘sanitised’ – with all references to Satanism removed”.

This might be due to the fact that Satanic Ritual Abuse, which she refers to directly and indirectly, does not and has never existed – at least, outside the imagination of conspiracy theorists and fundamentalist Christians. It might also be due to the fact that the other complainer is the Fresh Start Foundation, who have a connection to Robert Green, an independent investigator who has been jailed twice over the Hollie Greig case, UK Column, a news website known for circulating right-wing conspiracy theories, and the grand dame of UK conspiracism, David Icke.

The Boleskine House Foundation stated that the site was not intended to become a place of “pilgrimage and ritual”, and that the connection to Crowley did not “directly influence its future use”. But this seems disingenuous; Keith Readdy, trustee of the Foundation, describes himself as an academic “researcher in comparative religion”, but his one publication, One Truth and One Vision: Aleister Crowley’s Spiritual Legacy, states that it is aimed primarily at Thelemites, and much of it is concerned with establishing the legitimacy of different OTO lineages. And there has certainly been a warm relationship between the Foundation and the OTO, though, after accusations of child abuse and an arson attack, you can understand why this isn’t being highlighted by the Readdys.

Even weirder, there have been other Crowley-related hit pieces this year – this one from the Daily Mail describes the Tree of Life (a standard element of Jewish mysticism for centuries) on the floor of an abandoned cottage Crowley once stayed in as “apparatus believed to have been used to try and contact demons”. This report concerns a man trying to sell a wax-splattered box supposedly found in the basement of Boleskine, despite the fact that it is of the kind which costs a few pounds from any head shop in the country and looks almost new.

So what’s the beef? Why take up valuable newspaper real estate at a time when there are other, more important things to write about. Funnily enough, this brings us back to QAnon. Both of these are inheritors of the Satanic Ritual Abuse panic of the 1980s and 1990s, predicated on the existence of an imaginary secret religion who deliberately invert Christian morality, and use sexual abuse and cannibalism in rituals. It is often conflated with real groups like Wiccans and the OTO, even though neither is Satanic, involved in ritual abuse, large enough to organise such things anyway and aren’t even particularly secretive. The same goes for the Church of Satan, as founded by Anton LaVey in 1966, which is probably best regarded as a particularly theatrical version of Humanism.

Creator: Ted Eytan. Via https://mancunion.com/2021/01/12/opinion-the-republican-party-is-complicit-in-the-attack-on-capitol-hill/. Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Nevertheless, large numbers of people believe that such an imagined Satanic Other exists. For most, this is probably just an internalisation of Christian narratives about good and evil, and of the existence of demons and devils. These implicit beliefs are stoked up by more active players, however, mostly (though not exclusively) Christian fundamentalists with an axe to grind, and who, because of the traditional association of Christianity with moral good, are able to speak into the ear of the press, police and politicians.

But there is certainly an aspect that is to do with defending the body politic against invasion – which is why such ideas tend to flare up at times of societal unrest, and why we see the same motifs popping up in antisemitic tracts from the Middle Ages to the Third Reich. So while the battle between good and evil plays out on the steps of the US Congress, it is also playing out in local newspapers and planning applications.