We’re on design as a set of Cognitive Superpowers (again).

This time looking at two properties we take for granted and don’t seem to include in learning outcomes: Attitudes and Behaviours.

I’m going to argue that these are as important as developing Skills or Cognitive Abilities. In particular, that they are necessary aspects of being a ‘general expert’ designer.

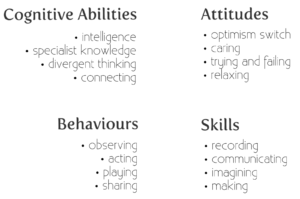

One starting point was an old Introduction to Creativity that highlighted the importance and ways of developing both these as well as skills and cognitive abilities and gave a few examples of each:

Another starting point is the work we are doing for the new Design qualification (more on this later!) and a renewed focus on the expertise, artistry and capacities expert designers develop in their careers.

Central to both of these is understanding how design expertise can be developed generally and without being taught in a specific subject domain (e.g. interior design, or interaction design). What is the general (or transferrable) expertise a practitioner gains from a design education? Not a specific domain expertise, like graphic design or haematology, but from the broader discipline around that? Like being a scientist, designer or mathematician?

In other word, what are the discipline level traits of expertise in design?

My feeling is that this type of expertise is likely to be a deeper cognitive property rather than the surface skills often associated with design expertise (see below for skills artistry, though). Various writers have looked at this but this work has never really been completed satisfactorily. Dorst and Reymen (2004) tried it but didn’t really get too far. Kimbell (2011) had a go but the focus was more on specific disciplinary artistry and expertise.

Let’s see if there’s another way to approach this.

First, consider what is special about the thinking and, especially, cognition that designers engage in. Perhaps even more accurately, we must also consider the cognitive states of mind: attitudes and behaviours – not just the ‘thinking’ we think we’re aware of (remember, 90% of our thinking is like this – we are just not ‘conscious’ of it). This is likely to be something similar to attitudes, behaviours, or states of mind brought to a setting. Or, if we do focus on skills, the deep embodied cognition that comes with true skill artistry (i.e. more than being able to knock out the chord of G on the guitar…)

I’m going to start with Cross, again, and that 1982 paper (Cross, 1982). This put a lot more detail on Bruce Archer’s work around design being a ‘third area’ of education.

Using that framing, what are the cognitive states we see in these areas?

For example, a scientist has to suspend belief and even question perception in order to go about the business of science. You can’t base observations on what you think has happened or even what your senses tell you. If you do, you’d end up with a lot of very strange religions and no one would know what time it is (or was. or will be).

For example, a scientist has to suspend belief and even question perception in order to go about the business of science. You can’t base observations on what you think has happened or even what your senses tell you. If you do, you’d end up with a lot of very strange religions and no one would know what time it is (or was. or will be).

To deliberately think this way takes effort, though. If we ‘feel’ that a piece of timber is warmer than metal after sitting for hours in a room, then just accepting that as ‘fact’ is far easier than questioning it, getting out the thermometer and going through the cognitive dissonance of reconciling your perception with an external measure. (a clue – timber and metal can be the same temperature

This could be thought of as sceptical thinking but it’s slightly more nuanced than that because it’s not always purely ‘conscious’ thinking. To catch your biased thinking is also notoriously tricky and doing this as part of a community of learners with expert guidance is one recognised way of doing this.

Let’s call this type of thinking an attitude – it’s more like a state of thinking, state of mind, or an approach to knowing about something. Most importantly, it is a learned, developed and advanced cognitive skill / process / state.

If we stick with the Cross framing, practitioners in the area of the humanities could be said to be to deliberately enter into other states of mind: to deliberately place oneself in a position of subjectivity and plurality; of experience and phenomena; of critique and exploration.

As with science, the easier thing to do is to simply experience the subjective state and no more. To deliberately act on the state of mind is the key difference (possibly) between the disciplinary and non-disciplinary position. More than this, it is the awareness of and response to this state that is, for some, critical evidence of deeper learning or of professional artistry.

In design, an attitude that is strikingly similar to the both examples is that of holding multiple realities in our heads and delaying decisions in order to explore. Like a scientist thinking sceptically or an artist experiencing subjectively, a designer has suspend decision-making for as long as possible in order allow new and different ideas to emerge. This requires a designer to not simply jump to the first solution – or even the second, or 78th…

Again, as with suspending your beliefs or perceptions, this can feel unnatural and takes energy. So many novice designers jump straight to solutions or engage superficially in options or deeper creative thinking strategies. (I did this too as a student – Ralph, you were right about that botanic garden project: I should have looked at more options and detailed changes… There. I said it.)

There are three common things between these examples:

- Effort – that each of these attitudes or approaches requires effort to suppress ‘normal’ cognition and implement an alternative state

- Attitude – A prior state of mind (disposition?) brought to a present context

- Behaviour – The deliberate and developed response to activity (as part of an identity or performed identity)

These all lead to a slightly different view of design, perhaps closer to “…the opposite of taking things for granted.” (Redström, 2020). And this all aligns with contemporary cognitive development theory in terms of us being thinking ‘optimisers’ (Dehaene, 2020).

So developing attitude, or disciplinary attitudes, takes effort, practise and support to develop them into behaviours as part of expert practice. It is also developed over time, as can be seen in the transition from novice to expert scientists, artists and designers – subtler and advanced expressions of such attitudes are very often found in all such expert practitioners.

But all too often this type of invisible expertise is overlooked in favour of superficial skills or misunderstood behavioural approaches.

We are pretty bad at talking about this sort of human capacity because it is far harder to measure and work with compared to skills. (actually, this may not be true – it may be that we have simply surrounded ourselves with the tools and methods to measure some things more successfully than other types of human development. Perhaps for some extrinsic reason…? Or perhaps some disciplines are just better at ‘owning’ these as competencies than others?)

The reason this matters is that, if we fail to treat design expertise as ‘seriously’ as other major disciplinary areas do, our students won’t get the best support possible to develop their own expertise and artistry. If design is seen as ‘just’ skills or ‘only’ being creative then we have the same disciplinary crisis Schön talked about way back in the 1980’s.

First, we need to recognise what type of properties these might be and then what they are – the examples above are just that and there are undoubtedly many more (and better examples).

Then, we need to start seeing the expertise it takes to become a designer a bit more seriously. It’s by doing that that we can then shift the design curriculum and create a far more sustainable version of lifelong learning.

References

Dorst, K. and Reymen, I. (2004) ‘Levels of expertise in design education’, Proceedings of the 2nd International Engineering and Product Design Education Conference, 2-3 September 2004, Delft, Delft University of Technology, pp. 159–166 [Online]. Available at https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/levels-of-expertise-in-design-education (Accessed 18 February 2021).

Leave a Reply