The IASDR2019, a biannual conference on design research, organised by the International Association of Societies for Design Research, brought together a truly international group of researchers and designers. This year’s theme ‘design revolutions’ steered some discussions around design and change. I asked myself: As we are living in a more and more chaotic and rebellious world, should design strive to create more stability or support the construction of radical new structures and societies? And might the latter be necessary to reach the former?

A Times Higher Education (THE) long read by Lennard Davis from the 5thof September, debates exactly the same topic – activism and subversion, not from a design perspective, but from the perspective of Art and Media studies and academia. The author wonders at what point flamboyance and or simply ‘behaving badly’ became synonymous with the ability to ‘change the world’. Davis argues that critiquing power structures by acting flamboyantly and subversively has never led to changing the existing power structures. At the same time, Davis conceded that being a good consumer of (or addict to?) iPhones and, I could add, binge-watching Netflix does neither.

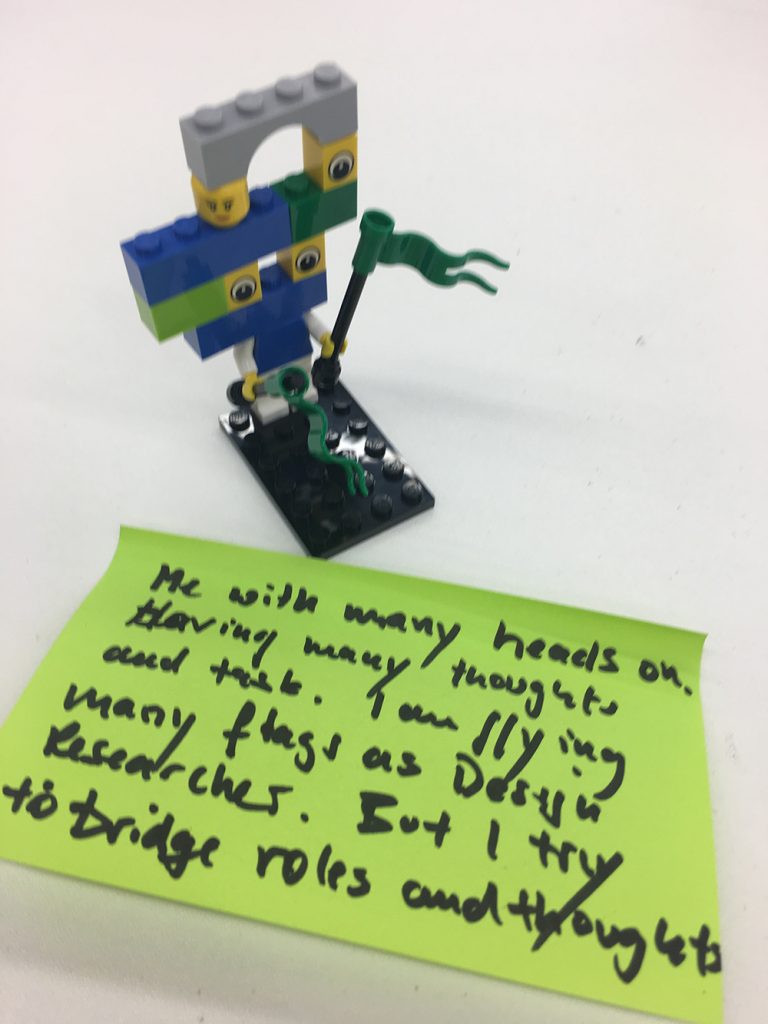

It is so disappointing to say: it probably needs a balance of subversion and humility to achieve change. Designers need to know when to be humble or when to be flamboyant, they need to be able to put themselves in different shoes or maybe just put a different hat on for a while. The greatest learning that I have taken out of the IASDR mini-workshop on ‘Documenting the reflective making’ is to be humble, to listen and not to change others meaning too quickly. We have been asked to build with Lego what we think represents us as designers/design researchers (look at the monster I have created ;). We were then asked to describe what we have built. The facilitators asked question to help us reflect more fully. But I noticed that there was something different about their questions. They were carefully worded, precise, simple, yet deep. The facilitators said that they take care to use the same words the storyteller used when they probe. Academics (and maybe designers too?) are often all too quick to put someone else’s story in their own words and concepts. Yes, this might superficially help us understand, but only what we want to understand. Does rewording actually just confirm our established thought structures and may it inhibit change?

Critical thinking is more than criticising, Clifford Choy from School of Design at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (where I did my PhD) argued over a lunch conversation. The conversation took us to the recent increasingly violent protests in Hong Kong. Clifford wondered out loud if the subject of critical thinking that integrated in the educational curriculum 20 years ago changed this generations’ approach to change. When critical thinking was introduced, the term was mistranslated into Chinese, meaning something more negative and subversive than the English phrase implies and was taught in the form of ‘criticising’. Design has the duty to not just criticise but offer a viable alternative that can be implemented to become reality and does not just remain an idea or blue sky thinking, as Cees the Bont (new Dean of the School of Design and Creative Arts in Loughborough) has argued in his keynote on day 4 of the conference.

La Campana market community space before and after community ‘design activism’

My presentation was about change. In previous posts, I have reported on the co-design of a Community FabLab in Monterrey. This has been running now for over 6 months and, on a small scale, we have achieved real change and impact. Community members now use the concreate casting method, that was introduced by Insitu in a community co-design workshops, to continue with the fabrication of community outdoor furniture. Community spaces are changed with the newly digitally fabricated objects. They now take the place of a filthy overflowing and misused rubbish container in the outdoor market of the neighbourhood. The meaning of this place is changed drastically from ‘I don’t care and this is a rubbish place’ to ‘let’s get together and let’s care about how our community space feels like and is used’. In this project, the designers and researchers aimed to be humble in their support to produce change while enabling activism and flamboyancy by community members.

A similar presentation reported on a project that uses plastic rubbish, collected locally from the ocean, to construct a boat, a ‘dhow’. East African boat builders used their skills and blueprints with this new material to construct a vessel that was meant to attract attention, be flamboyant and subversive. The local boatbuilders undertook a journey along the coast from village to village to show the vessel and spread the word of how it was constructed. When they stopped the boat along the journey, they used storytelling to engage communities. They told a simple story, this boat is built from recycled plastics and coated with discarded flip-flops. It may look different but it is still a traditional dhow. You can build it too! All the resources and skills are available to you. One community member tells others how it works. The design researchers, who got the money to fund the project, stand back and let the communities tell their story. In both cases, the designers are humble to support flamboyant community participants to achieve real change for their communities.

I attended many more interesting talks, workshops and a ‘handling session’, in which digitally fabricated objects could be touched and questions to the collectors could be asked. A comment struck with me. Digital printing is now as common as any technique. What is revolutionary is to push the boundaries, this is what the collection is about. Many objects do that by integrating digital and hand-crafted techniques to fabricate these objects. Three objects I particularly liked are below. An object produced with a filament containing iron particles and magnets. An object cast into a patterned frame and baked. 3D printed fabric.

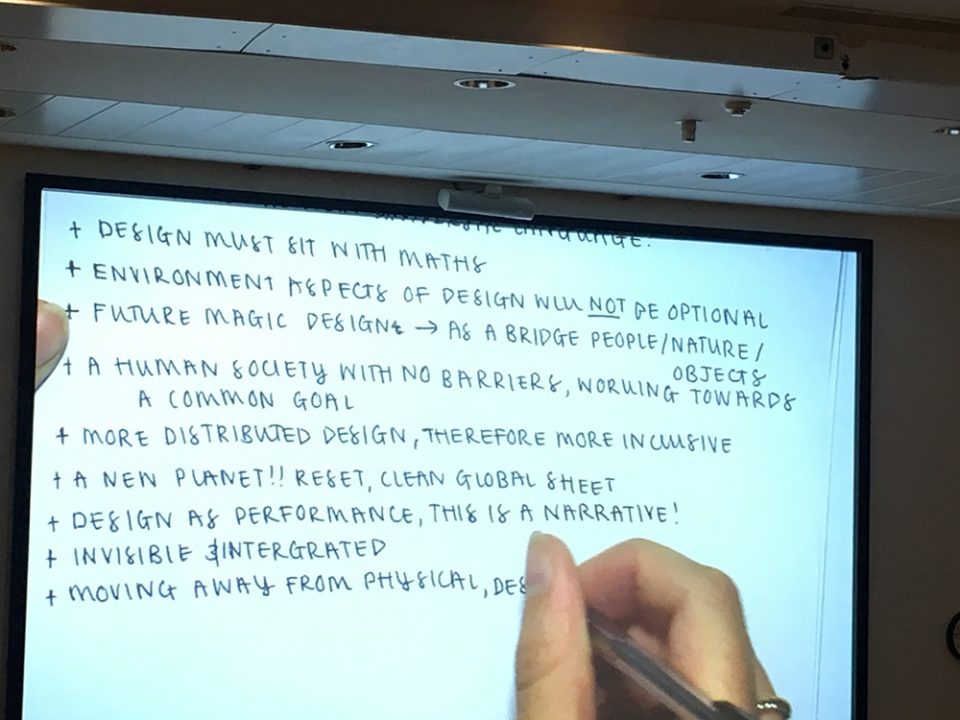

Because there were so many overlaps, there were also talks I could not attend but would have loved to, such as from our PhD students Erika Illaregi and Tom Morton. And sadly I had to chair a session when Katerina Alexiou and Theodore Zamenopoulos were talking. The conference closed with an audience discussion on: “What will design look like in 75 years from now?” Here are some notes from the audience. What do you think?

Leave a Reply