As Rishi Sunak nears the end of his first month in the job as Prime Minister, we might once again consider how much he might engage with, and progress, the European issue.

Like his predecessors before him, Sunak has both a vague sense that this is something that needs sorting, and no real plan about how to sort it. I leave it to others to muse further on the extent to which cakeist thinking – why can’t we just have all the good stuff? – has spread across Westminster, to the disadvantage of considered policy-making.

In broad terms, Sunak looks a lot like Liz Truss in his EU policy so far: warm words, but no desire/ability to move on substance. Unlike Boris Johnson, with his visceral unwillingness to be seen to do anything with the EU or ‘Europe’, Sunak and Truss both made the choice to try a more conciliatory tone and to be seen talking and working with European counterparts.

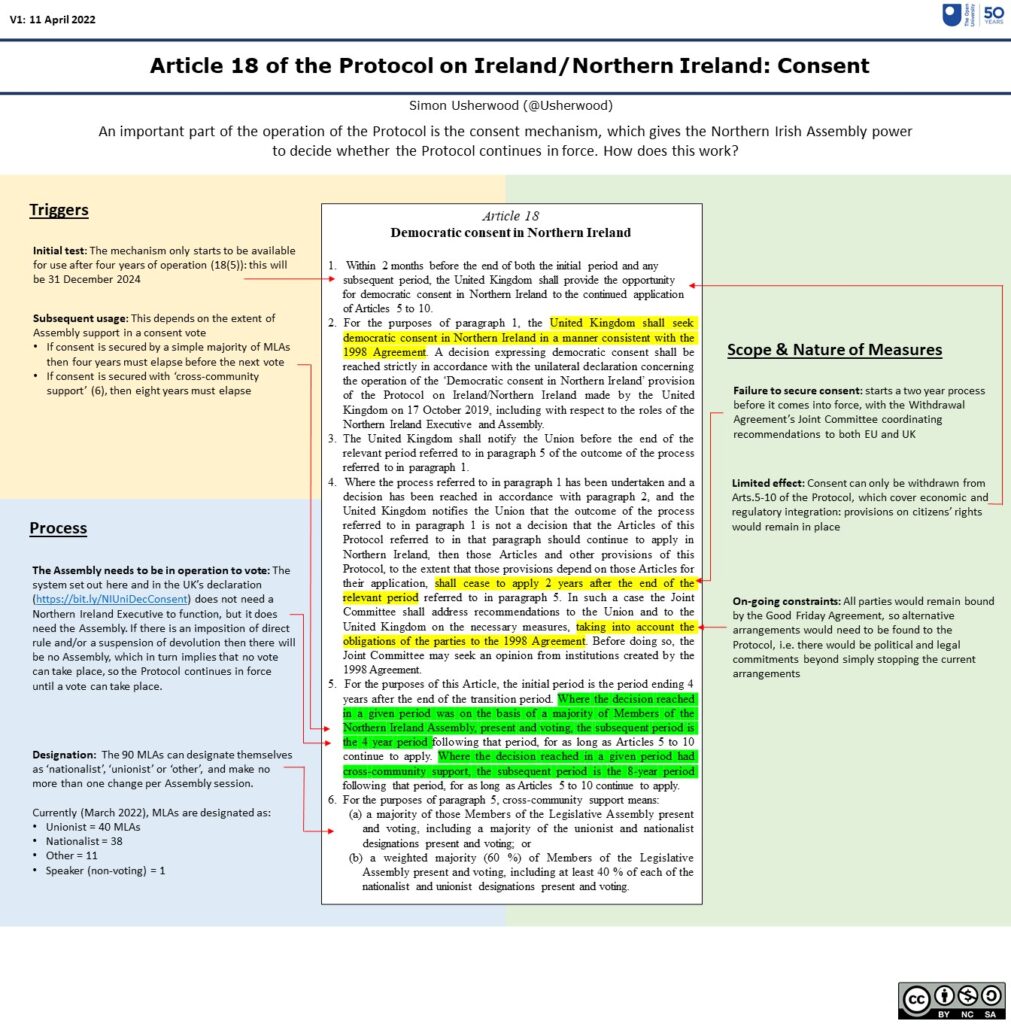

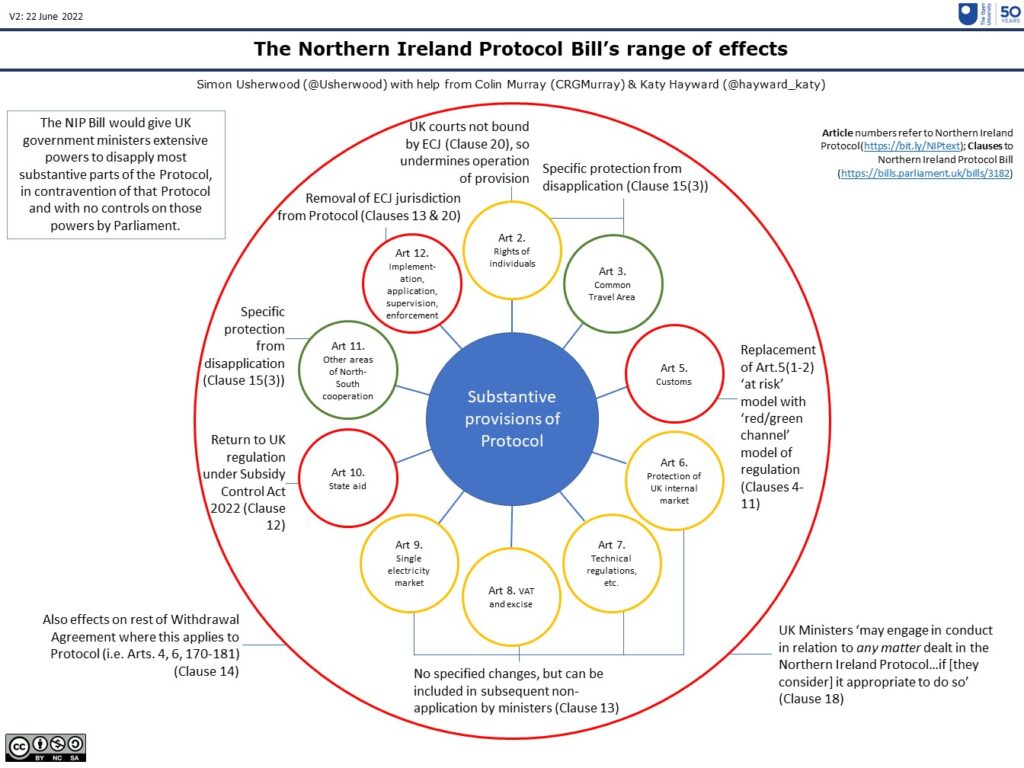

This is most clearly seen in the Northern Irish element of relations, as set out in the graphic below:

PDF: bit.ly/UshGraphic110

This post-Johnson shift requires some explanation, since it is likely to be the key dynamic for the rest of Sunak’s time in office.

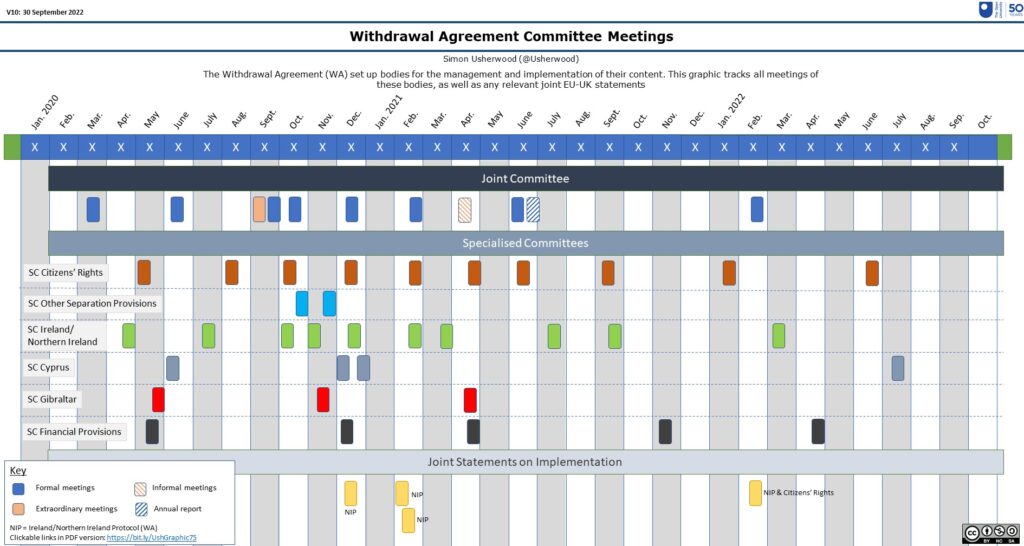

As the next graphic suggests, there are several things going on here:

There are plenty of good reasons for Sunak to seek a settlement with the EU, especially over the Protocol, but these have to be balanced against the more localised constraints he faces. Backbench ERG types have already made it clear they are willing to cause trouble if he drifts off the current baseline, trouble that might be more logically focused on Sunak’s hold on the party leadership – which still looks shaky in the Williamson/Braverman/Raab context of poor ministerial selections – than on EU policy per se.

The short-term squaring of this has been the warm words pitch: say the nice things, sign up to the collective actions on unproblematic (in the domestic sense) topics and hope to ride it out.

But as the graphic also notes, this can’t work for very long.

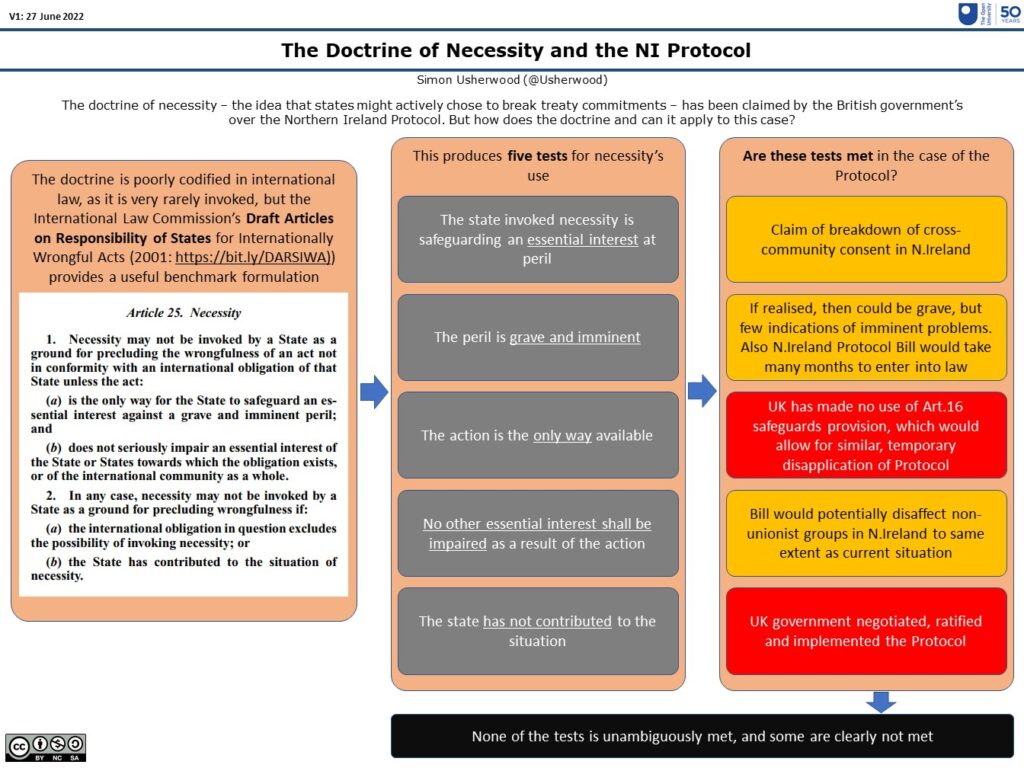

The passages of the NI Protocol Bill and the Retained EU Law Bill through Parliament mean that two major headaches are on their way in relatively short order. Each causes new points of tension with the EU just by their existence, even if provisions are not implemented: the hair trigger powers the government would hold are another clear substantive step back from the good faith pitch that Sunak wants to communicate.

Given no apparent willingness to pull or slow the Bills, Sunak will find that warm words aren’t going to suffice, especially if he really wants a resolution for Northern Ireland by the Good Friday Agreement anniversary next spring.

This is all sufficiently clear that choices will have to be made quite soon.

Sunak can step in to do something about the Bills, or he can invest major political capital in trying to mediate in Belfast, or he can chose to let it drift and hope for the best.

Brexit history suggests that the last of this is most likely, leaving everyone having to scramble to find another solution to a situation that never needed to have come about in the first place.

The question of whether and how Ukraine joins the EU ranks relatively low on the list of priority topics right now, for reasons that are both too obvious and too horrific to discuss right now.

The question of whether and how Ukraine joins the EU ranks relatively low on the list of priority topics right now, for reasons that are both too obvious and too horrific to discuss right now.