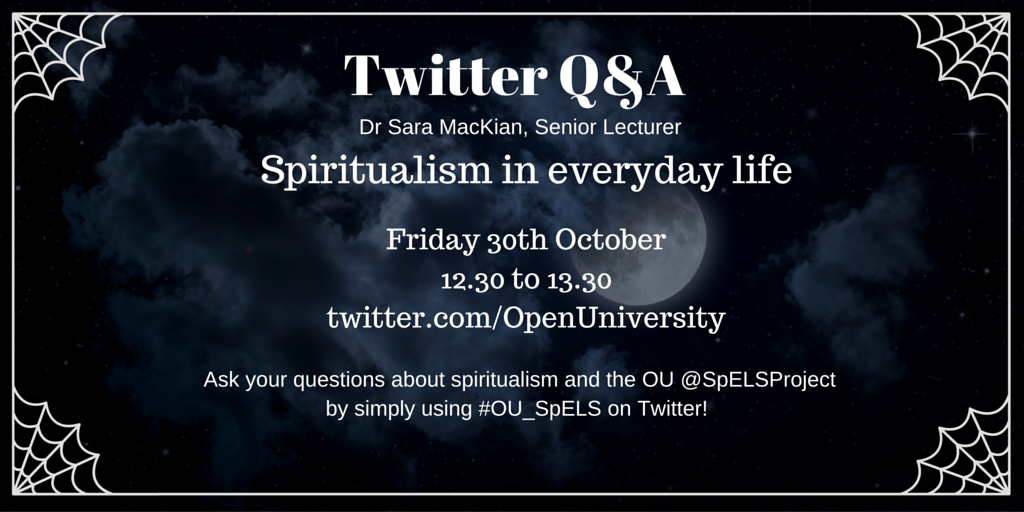

It is with some trepidation that I am looking forward to taking part in a Twitter Q&A session tomorrow, hosted by the Open University and based on our research project ‘Spiritualism in the Everyday Life of Stoke-on-Trent’.

It is with some trepidation that I am looking forward to taking part in a Twitter Q&A session tomorrow, hosted by the Open University and based on our research project ‘Spiritualism in the Everyday Life of Stoke-on-Trent’.

The OU run these things with their academics frequently and, as usual, advertised the forthcoming session amongst their followers earlier this week. Sometimes they get a lot of people taking part, sometimes very few; but the aim is always to open a conversation about areas of research that are ongoing amongst the research community at the university.

Now I know Spiritualism isn’t everybody’s cup of tea; and that is fair enough. Nonetheless, it has been a part of the religious landscape of Britain since the 1850s, and for its community of followers it has brought comfort, faith, friendship and laughter through good times and bad. Just like any other religion.

However, Spiritualism also attracts an incredibly negative – often hostile – response from some people. We have first-hand experience of that from our research fieldwork. When our associated exhibition (Talking With The Dead) opened, one commentator on Facebook said:

I hope that this exhibition doesn’t sanitise what, in other circumstances,

would be called a fundamentally morbid cult. A cult that cynically preys

on the bereaved person’s love for their dead relative, and thus dangerously

warps and freezes the grieving and healing process. I hope it also acknowledges

the movement’s historical support for pseudo-science ‘research’, and its

tolerance of fakery.

In some ways the comment was perfect for us in terms of highlighting the need for this research in the first place – because it summarised so succinctly some of the widespread misunderstandings and prejudices that surround this long-established faith. This person clearly felt very strongly but appeared to be basing his criticisms on a very outdated and limited understanding of what Spiritualism actually is. The experience for many thousands of British people is very different, and his description is not one which its practitioners would recognise.

It was also interesting that he mentioned healing – because healing is a key part of Spiritualist philosophy, and indeed spiritual healing is now widely provided in the NHS as a beneficial therapeutic intervention for people living with chronic long-term health problems.

Thankfully there have been only positive responses elsewhere to our exhibition and the research project as a whole; but Twitter is seems promises to be a very different beast. Within hours of the Open University Tweeting the Q&A event we were being ridiculed. It wasn’t just Spiritualism under attack, however; this became a critique of the Open University itself, of me personally, and of the wider research community.

I found myself wondering if my colleagues in Religious Studies conducting research into Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and various Indigenous peoples’ religions from around the world get the same criticisms levelled at them. We live in a country which, by and large, prides itself on its cultural tolerance. Paradoxically, extremism in many forms is on the rise. Social science can play a key role in trying to understand how and why that arises, and how we might be able to overcome it. Social science plays a key role in understanding the way society works, how people live together in peace, and how we can help to forge a better future. And part of that is to understand the role of religion and spiritual belief in all its guises.

So for those of you who have already ripped the project apart, criticising the OU and the research team for conducting this project, I wonder if you might be able to set aside your fears, and challenge yourself to learn something informed about this unique part of Britain’s history which continues to play a growing role in society today.