OU PhD student Sarah Middle reports on the Researching Born-Digital Archives workshop.

On Thursday 16 March 2017 I attended Researching Born-Digital Archives at the British Library, a collaborative workshop with three AHRC consortia – CHASE (who provide my PhD funding), South West and Wales, and WRoCAH. The focus of the day was on managing, curating and using collections of objects that had originated in a digital format (as opposed to digitisation of physical materials), and how the nature of these resources might lead to the study of new research topics.

British Library Initiatives

Several speakers from the British Library presented on the theme of managing the lifecycle of born-digital materials, from initial processing (Jonathan Pledge and Eleanor Dickens) through to long-term preservation (Maureen Pennock) and creative methods of reuse (Stella Wisdom). As a former collections professional, and current data enthusiast, particular points of interest for me included the processes involved in turning the files and directory structure of e.g. a floppy disk into an archive collection of digital objects, as well as the innovative ways in which people have reused the British Library’s publicly available datasets.

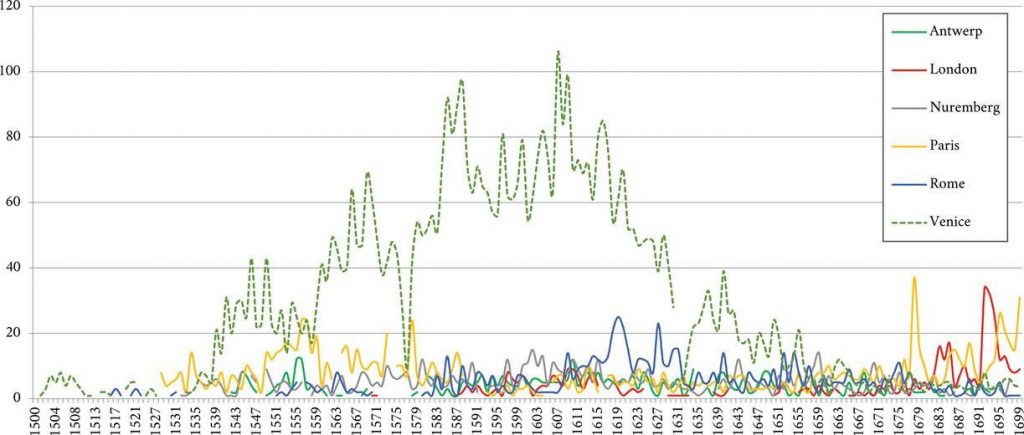

One project that stood out for me was the Big Data History of Music, which used library catalogue data to visualise trends relating to music production over time, by geographical location, and in relation to historical events. Stella’s talk was very inspiring, and prompted me to consider whether I might be able to make use of the library’s data as part of my PhD research.

Annual output of printed music for six major cities, 1500–1699. Data from RISM A/I and B/I (Stephen Rose, Sandra Tuppen, Loukia Drosopoulou, ‘Writing a Big Data history of music’, Early Music 43 (2015), 649-60 doi: 10.1093/em/cav071; distributed under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution licence)

Born-Digital Archives and Creative Writing

Another theme from some of the talks was the impact of born-digital archives on the research and practice of creative writing, presented here from the point of view of an archivist (Justine Mann, University of East Anglia) and a writer (Craig Taylor). Justine spoke about collecting the ongoing work of emerging contemporary authors and preserving it in a born-digital archive, which will allow future researchers to gain an unprecedented insight into their creative processes. Craig is working with the British Library on his current project, Genesis, which involves writing his latest novel on a dedicated laptop with spyware installed. Every keystroke is recorded, documenting his creative process in minute detail.

One particularly interesting question from the audience was whether authors are more self-conscious in the production of their digital materials, in the knowledge that they will be archived, and whether this has an effect on their content (e.g. wanting to present themselves in a certain way). It is not yet possible to answer this question fully; however Craig said that, while he usually forgets that the spyware is there, he becomes very aware of it at points where he is struggling. Perhaps this question might form the basis of a future research topic years from now.

Student Panel

A particularly exciting aspect of the event for me was the opportunity to present my work as part of a student panel, with three other AHRC-funded PhD students. Helen Piel (British Library / University of Leeds) started by talking about her work with the different materials held in the British Library’s John Maynard Smith archive, containing the various works relating to his research interests in the areas of Engineering and Zoology. Kate Walker (University of Sheffield) then spoke about her research, which focuses on social media communities of wadaiko (Japanese drum) players, and involves collecting data from Facebook groups of which Kate herself is an active member. Acatia Finbow (Tate and University of Exeter) is studying documentation of performance art at Tate Modern, which similarly includes a large amount of social media content, but with more focus on image and video, rather than text.

Student panel discussion, including Helen Piel (left) and Acatia Finbow (right) (unfortunately Kate Walker and I are hidden by the audience) (image via @UEAArchives on Twitter)

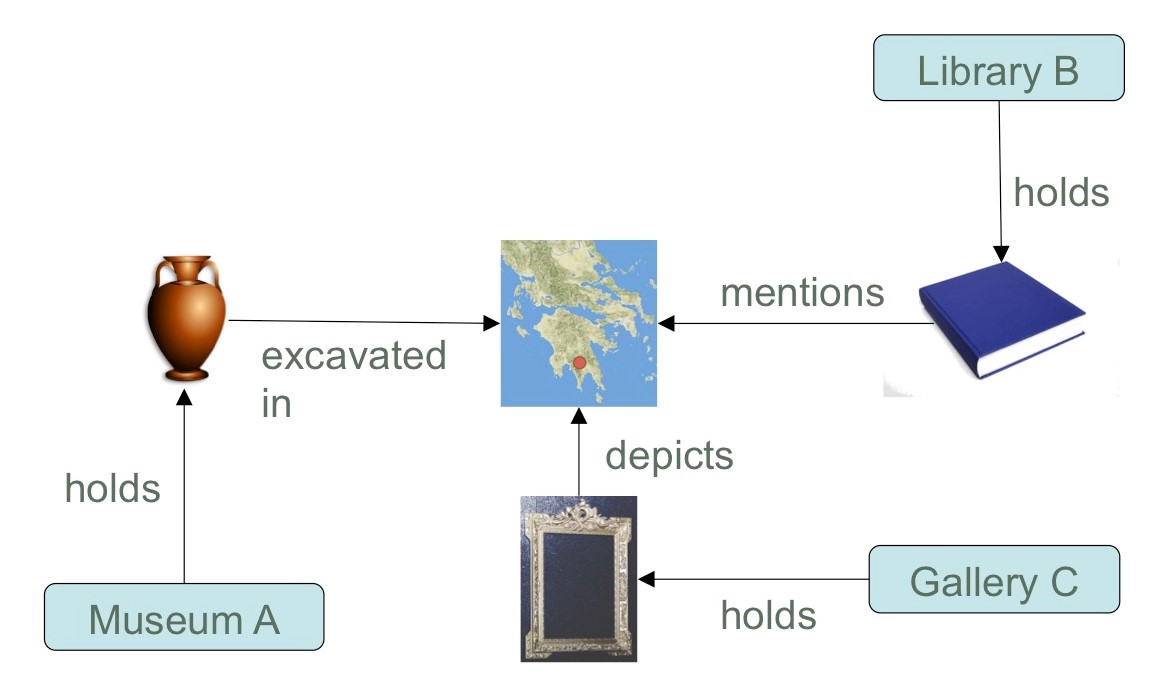

I gave a brief overview of my work converting the AHRC project data held in the Research Councils UK’s Gateway to Research (GTR) to Linked Data (of which more in a future post). My focus was on the differences in data structures between the existing GTR and the Linked Data, and how the Linked Data structure allows more complex queries, which will help me identify projects to use as case studies as part of my future research. I was quite nervous, as it was the first time I had presented on my PhD research, but my talk seemed to go well, and I received many positive comments afterwards. Several people said they had not heard of Linked Data previously, but understood my explanation, which indicates I had managed to pitch it at the right level – always an issue when explaining technical concepts to a non-specialist audience.

A simplified example of how Linked Data can be applied to Humanities collections, based on the idea of Pelagios

Final Thoughts

As well as providing the experience of presenting my research in a friendly and supportive environment, I found this event an interesting and stimulating half-day. It provided me with a strong foundation of knowledge in the various stages involved in managing born-digital collections, as well as their potential for opening up new areas of academic research. In particular, I really enjoyed meeting academics, professionals, and other PhD students from all over the country, who are working in areas relating to digital collections. I would like to thank the British Library and the three AHRC consortia for organising the event and for making my attendance possible.

by Sarah Middle

Editor’s note: To find out more about Sarah and her PhD research, take a look at the OU Classical Studies blogpost ‘ Introducing …some of our new PhD students!‘

Both sets of students had the opportunity to study Classics because their outstanding teachers have — in their own time — trained themselves to deliver the course material. It is a sad truth that if it wasn’t for the extraordinary energy and passion of teachers such as Paul Found (pictured left) and Eddie Barnett, the cultural remains of the Greek and Roman worlds would scarcely feature in the formal education of children in the UK outside of fee-paying schools. I am happy to report that more teachers are already following Eddie and Paul’s pioneering example!

Both sets of students had the opportunity to study Classics because their outstanding teachers have — in their own time — trained themselves to deliver the course material. It is a sad truth that if it wasn’t for the extraordinary energy and passion of teachers such as Paul Found (pictured left) and Eddie Barnett, the cultural remains of the Greek and Roman worlds would scarcely feature in the formal education of children in the UK outside of fee-paying schools. I am happy to report that more teachers are already following Eddie and Paul’s pioneering example!