I’m a geologist who now works mostly on other worlds, and the one that is keeping me busiest at present is Mercury. This is the closest planet to the Sun, which means that is always much closer to Earth than Jupiter ever gets.

However, it is harder to study because the Sun’s glare makes it difficult to observe with telescopes, and the Sun’s gravity poses an enormous challenge if you want to get a spacecraft into orbit about Mercury.

NASA achieved this with its MESSENGER orbiter (2011-2015), and I’m on the science team for the European Space Agency’s BepiColombo orbiter 2024-2025, due for launch in later 2016.

2015 Science Matters Lecture

I recently introduced school students, teachers and members of the public from Milton Keynes to my research at the 2015 Science Matters lectures.

You can watch a recording of my talk below.

What do we know about the planet Mercury?

There are many reasons why Mercury is turning out to be special. For one thing, its closeness to the Sun means that it experiences similar conditions to those affecting the most easily detected planets of other stars, known as exoplanets.

The rocky (terrestrial) planets plus the Moon, all to scale. From left to right: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Moon, Mars.

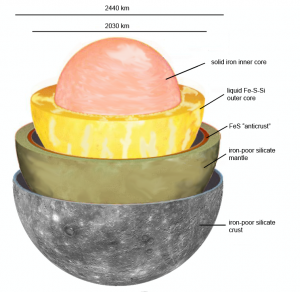

Mercury is the only rocky planet other than the Earth to generate its own magnetic field, so there must be a liquid, molten, zone in its iron-rich core.

Mercury is a dense planet, so its core must make up a much greater proportion of the planet’s volume than in the case of the Earth.

In fact, the rocky mantle and crust surrounding Mercury’s core is probably not much more than 400 km thick. The rocky surface appears to have been formed by a succession of giant volcanic lava flows, most of which happened billions of years ago so that there has been plenty of time for vast numbers of impact craters to form as a result of bombardment by asteroids and comets.

The comparatively small amount of rock surrounding the core compared to the other rocky planets suggests that Mercury had a violent birth, in which most of its original rock was stripped away – perhaps as the result of an enormous collision with another planet.

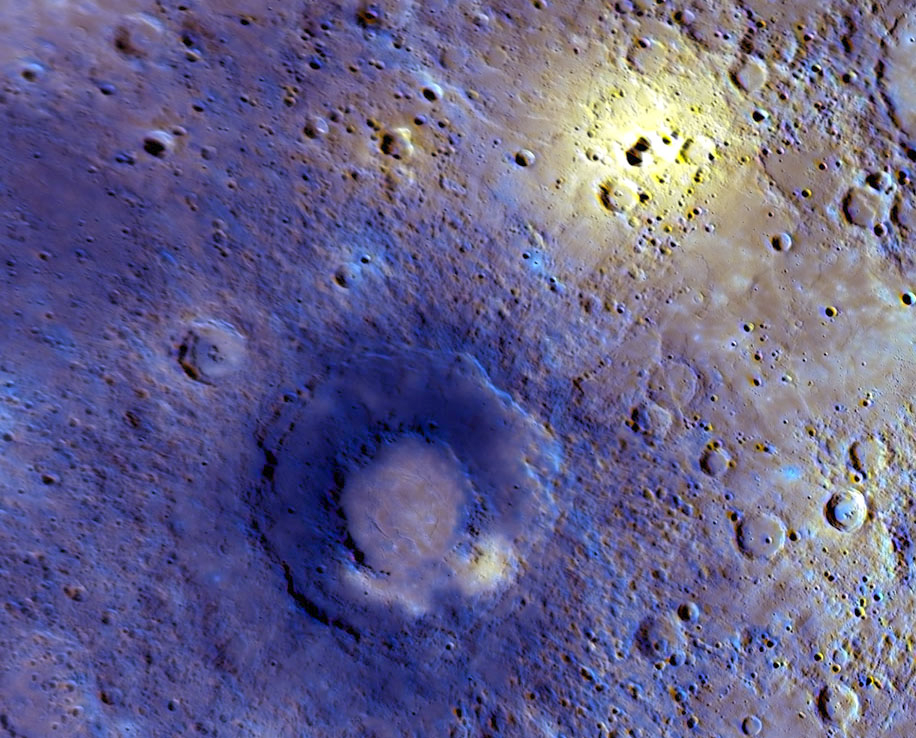

1700 km wide view from MESSENGER, including the edge of Mercury’s northern volcanic plains (NASA/JHUAPL/CIW)

The significance of NASA’s MESSENGER orbiter

This idea has been severely challenged by MESSENGER data, which show that Mercury is rich in volatile elements of the kind that would have been most easily lost during hot, violent events. For example:

- wherever MESSENGER looked, the surface has 2-5% sulfur;

- the ratio of potassium to thorium is high;

- there are places where patches on the surface seem to have been vaporized;

- and the globe is peppered with volcanic vents where explosive eruptions have happened, driven by violent expansion of gas bubbles in the magma.

What don’t we (yet) know about the planet Mercury?

One of the joys of conducting research is finding out new things. For example:

- we don’t know what has been removed from the vaporized patches of surface;

- we don’t know what the gases were that drove the explosive eruptions;

- and we don’t know whether the sulfur occurs as elemental sulfur or in compounds such as magnesium or calcium sulfide.

We also don’t know when the most recent volcanic explosions occurred, but work by Rebecca Thomas, one of my students, suggests that activity continued into the past billion years.

910 km MESSENGER view of Mercury. The large yellow spot at top right is a deposit from an explosive volcanic eruption from the deeply-shadowed vent at its centre. The smaller yellow spot in below the middle of the frame is a similar deposit, from a vent too small to make out. (NASA/JHUAPL/CIW)

Locating Mercury in the night sky

Mercury is hard to see for yourself. You’ll have a chance to see the planet in late April-early May 2015, when Mercury will be slightly higher on the evening sky after sunset. See here for an animation of Mercury and other planets in the evening sky of early 2015.

An even better chance, of a different kind, will be 12:12-19:42 BST on Monday 9 May 2016 when Mercury will cross the face of the Sun. Simple equipment will enable to see it then in silhouette. I hope also to be able to stream live images on the internet from at least one ESA satellite, and to make the day a Europe-wide Mercury party as part of the build up towards the launch of BepiColombo.

If you share my passion for planets, you might be interested in my nice and cheap Very Short Introduction to Planets.

Alternatively, if you want to read about Mercury in greater depth then seek out Planet Mercury: from Pale Pink Dot to Dynamic World.