Professor Richard Holliman, The Open University.

A recent report, published by an independent consultancy firm, discusses what they describe as the “hidden economic value of public engagement and knowledge exchange in UK universities” (Viewforth Consulting, 2018).

The quoted figures are certainly eye-catching. Based on extrapolating the data from 1093 university staff from three UK universities the authors of the report argue that, “UK university staff delivered 40 million hours of pro-bono public engagement and knowledge exchange in 2015-16”.

Boom!

Putting the calculation of the figures aside for one moment, the report invites a crucial question around the following sentence (my emphasis):

This evidence indicates that university staff, with the approval and encouragement of their host institutions, provide a large and economically significant volume of public service and knowledge exchange to UK society on a voluntary basis.

(Viewforth Consulting, 2018: 2)

On the face of it, this appears to be a contradiction. Can you work in a voluntary capacity with the approval and encouragement of your employer? And what does approval versus encouragement mean in this context? They’re clearly not the same thing.

Further, how much of this activity was funded, directly or indirectly through HEIF (and equivalent schemes in the nations), Pathways to Impact funding, or through QR funding as a result of REF 2014? How much of the support for Widening Participation has contributed to teaching income and/or the TEF?

When is engagement not work?

The report raises a really important question: When are public engagement and knowledge exchange not work? When these activities are voluntary seems to be an obvious answer. Hence, the confusion arising from the sentence above.

Put simply, were the respondents working or volunteering when they described their engagement activities in their survey responses? I’m guessing that they replied as if they were working, but is this fair?

Is media engagement work? Explore your answers using The snakes and ladders of social media. Poster design: Peter Devine

Perhaps they were working with the approval of their employer? Alternatively, could they have been volunteering with the encouragement of their employer? I don’t think they can be doing both at the same time, and it is a significant distinction.

It follows that one of the key, and as yet unresolved, issues for university employers and staff working in public engagement and knowledge exchange is where the boundary between what is agreed and supported as work and what is voluntary and conducted outside of work lies. Research indicates that this is often the same situation for communication activities (Grand et al. 2016).

It follows that, in my experience the work/volunteering boundary is frequently blurred, often to the detriment of those who value public engagement and knowledge exchange and do it well (Jensen and Holliman, 2016).

Valuing productive work

Ask yourself this question: Have you ever been left feeling resentful that your public engagement and knowledge exchange work doesn’t seem to be valued by your university? If your answer is yes, could it be down to this work not being resourced in terms of time and funding, and recognised when it’s done really well?

Let’s be clear here, I’m not trying to discourage people from conducting public engagement and knowledge exchange work. Part of my role at the OU is to support excellence in engaged research (Holliman, 2017). Rather, I’m keen to encourage people to carefully consider in what capacity they conduct their contributions to public engagement and knowledge exchange.

If you want public engagement and knowledge exchange to be seen as work you need to agree this upstream with your Line Manager (or supervisor(s) if you’re a PhD candidate). Line Managers need to carefully consider their priorities and ensure that engagement and knowledge exchange are included as supported activities. Go crazy; build in some time for contingencies so staff can respond to strategically important opportunities as they arise.

If you’re coordinating a Graduate School, Doctoral Training Partnership, or working as a supervisor, ensure that you offer PhD candidate’s structured opportunities to enhance their CVs and future job prospects by gaining skills in engagement and communication (Holliman and Warren, 2017).

If your Line Manager/PhD supervisor agree, it is your responsibility to lead your engagement work effectively. Plan for the work in collaboration with those likely to be affected; agree your aims and objectives with them and, crucially, include measures to review performance (Holliman et al. 2018; 2017; Holliman and Davies, 2015).

If your Line Manager/Supervisor(s) is/are happy that the aims and objectives have been met, this will increase the likelihood that you’ll have time and resources allocated to plan for future activities. Sustain your excellence in engagement over time and you should have evidence to support career progression (Holliman et al. 2015).

Volunteering is a positive choice

What happens if your Line Manager or supervisor is not willing to support your public engagement and knowledge exchange work?

You have a key decision to make. Do you (still) want to plan for the work in collaboration with those likely to be affected as a volunteer; agreeing your aims and objectives as part of this collective of citizens, and including measures to review whether you achieved your goals? The outcomes won’t be REF-able, KEF-able or TEF-able, and you won’t be able to use your university brand and equipment. But you could still make a difference to people’s lives.

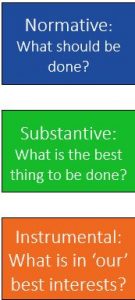

Exploring normative, substantive and instrumental rationales for decision making (see Holliman, 2017 for discussion).

And you don’t have to do this work completely on your own. There are a good number of organisations, some very well-established, that support volunteering in public engagement. You’ll need to comply with their requirements if you are to volunteer for them, but you’ll be part of a community with advice and support.

Managing your freedom to engage

A final point before I receive a barrage of complaints about how management-focused and instrumental this approach looks to staff who have dedicated many years to public engagement and knowledge exchange work in the past, often without support and recognition.

I’m guessing that you engage for three main reasons: 1) because you love your disciplinary field and want to spread the word; 2) you enjoy the freedom and fun that engagement activities offer; and 3) you’re keen to make a difference, e.g. in improving people’s lives and/or encouraging people to get involved with your disciplinary field in some way.

You can obviously achieve these ends through work (if it is supported) or through volunteering (seeking relevant support). Alternatively, you can choose not to engage. But don’t be resentful about the past; take control.

The ball is in your court and it’s a great time of year to start discussing this with your Line Manager. Planning is in train for the next academic year; workloads will be negotiated in the coming months.

If you want to continue to engage in muddy waters, be clear that this your choice. If you want to make things transparent, ask the question of your Line Manager. Agree time commitments, resources and performance measures with an agreement to review progress in a year.

At least that way you’ll know where you stand the next time you complete a survey about your public engagement and knowledge exchange work, as an (un)engaged employee, volunteer or citizen.

Acknowledgements

The research discussed in this paper was supported through the following awards: RCUK Public Engagement with Research Catalyst (EP/J020087/1); RCUK School University Partnership Initiative (EP/K027786/1); and a NERC Innovation Award (NE/L002493/1).