Dr Vickie Curtis, University of Glasgow

Can projects increase the inclusivity of scientific research?

Citizen science is a collective term for projects that engage both professional scientists and non-specialists in the process of gathering, evaluating or computing scientific data.

The number and scope of citizen science projects has increased dramatically over the past two decades – much of this is a direct result of developments in information and communication technology (ICT) and the Internet.

Some citizen science projects are now conducted entirely via the Internet and participants help to analyse large sets of data that have been provided by scientists.

How and why people participate in such projects are the subjects of my new book Online Citizen Science and the Widening of Academia.

Some projects have attracted thousands of registered participants, leading some to claim that they open up scientific research and ‘democratise’ science. But how inclusive are they in reality?

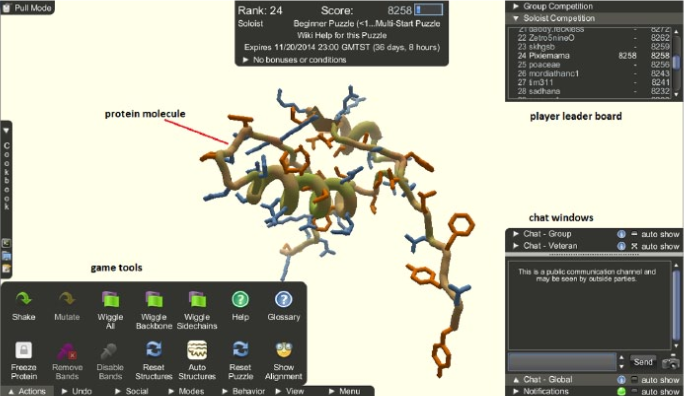

I looked closely at three projects over a period of three years: the online game Foldit, Planet Hunters (from the Zooniverse platform) and the distributed computing project Folding@home.

I explored patterns of participation and surveyed nearly 600 participants. I conducted interviews with small groups of active participants, and with the scientists and developers who set up and manage the projects. I also collated data that had been gathered by other researchers.

Foldit; https://fold.it/portal

Perhaps one of the most striking observations I made, was of the demographic characteristics of participants. I found that the majority of my survey respondents were male, well-educated (often with a tertiary qualification in a STEM subject), had an existing interest in science (regularly taking part in other types of science-related activities), and were mostly found in developed, Anglophone countries.

While these observations may not accurately represent the entire population of participants, it is interesting that similar observations have been made in other projects.

What this data may be telling us is that these projects attract certain groups. Despite the efforts of organisers to keep project tasks relatively simple and accessible ‘to everyone’, they attract mainly pre-existing ‘fans of science’.

Projects appear to appeal less to those who are from what has become known as ‘under-served communities’ and to those with lower levels of science capital.

Science capital is a concept that refers to aspects of cultural and social capital that have a specific scientific focus and includes science literacy, consumption of science-related media, taking opportunities for informal science learning, knowing people who work in science-related jobs, and talking to others about science in informal social settings.

While citizen science certainly has the potential to include many people in the research process who wouldn’t normally have any involvement, the data indicates that there is still much work to do if it is to be more widely appealing and accessible to broader groups of participants. How might this be done?

Moving online citizen science into the classroom could be one approach that may help to increase the diversity of participants simply by making it part of the science curriculum, rather than a voluntary extracurricular activity.

Using online citizen science projects can help to introduce authentic scientific research to a range of ages and abilities, particularly in communities where there is low science capital.

Online Citizen Science and the Widening of Academia. Distributed Engagement with Research and Knowledge Production by Vickie Curtis.

Online citizen science may have some advantages over other types of citizen science projects in that it doesn’t require any contribution of data, or as many resources (apart from a computer and connection to the Internet), and students do not have to leave the confines of the classroom which can be difficult to organise at times.

Another interesting development has been the increasing number of citizen science apps for mobile devices. Given the novelty of the technology, they may be more appealing to younger people and could help them to become more engaged with science and nature by providing data and observations to researchers, or by asking their own research questions.

The ubiquity and global reach of smartphones is growing rapidly and this could result in a greater diversity of participants. We may start to see greater participation in countries of the Global South, and in countries such as China and India.

It is likely that citizen science apps will constitute an important component of the next generation of citizen science projects, although more research is needed to explore their appeal more fully.

However, being more inclusive also requires thinking more deeply about science capital – either in terms of who has it, but also in relation to building it.

Scientists who set up projects often have public engagement or improving scientific literacy as one of their goals, and thus want to build upon the science capital of their participants. Their projects need to be structured in ways that appeal to a wider range of potential participants and this means recognising that not everyone will respond to project parameters in the same way.

This could be achieved through greater consultation with potential audiences during project development, and direct promotion of projects to specific groups.

There is still work to do, but online citizen science has tremendous potential to increase inclusivity in research and to build science capital in a wide range of audiences.

Online Citizen Science and the Widening of Academia. Distributed Engagement with Research and Knowledge Production by Vickie Curtis is published by Palgrave Macmillan as part of the Palgrave Studies in Alternative Education.

Reference

Curtis, V. (2018). Online Citizen Science and the Widening of Academia: Distributed Engagement with Research and Knowledge Production. Palgrave Studies in Alternative Education. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. Online: http://oro.open.ac.uk/55587.

Biography

Dr Vickie Curtis is based at the University of Glasgow where she is a Public Engagement Manager at the Wellcome Centre for Molecular Parasitology.

Acknowledgements

Much of the research that is included in the book was carried out at the Institute of Educational Technology at the Open University in the United Kingdom, and was generously funded by the OU’s Centre for Research into Education and Educational Technology (CREET).