By Lucy May Constantini

In 2002, back in the days when it was the hand-to-mouth existence of an independent dance artist and not global pandemics that curtailed my ability to travel, I fulfilled a childhood ambition and got myself to India. I went to take part in Facets, an international choreography laboratory, organised by Attakkalari Dance Company in Bangalore, where for three intense weeks, sixty or so dancers hothoused traditional Indian movement practices, Western contemporary dance, and digital arts. The first class every morning of my second week was taught by G. Sathyanarayanan Nair of CVN Kalari Sangham in Trivandrum, where he introduced us to the principles of the South Indian martial art kaḷarippayaṟṟ˘. I was bewitched.

In those three weeks we only had two days off and our dancing days generally ran from around 9:00 am to a similar time at night, so it’s no surprise I got ill. Thanks to an unhappy history with allopathic medicine, I determined to find an āyurvedic alternative, āyurveda being one of India’s traditional medicines. One of my new-found colleagues popped me on the back of his motorbike and took me to the local clinic, where my pulse was read and I was given a potion to brew for the immediate illness, and huge quantities of medicated ghee to prevent it recurring. Unwittingly, here began my exploration of physical practice melded to a healing modality. It’s perhaps no coincidence that my colleague guiding me to the clinic had himself grown up in Kerala, the southwestern state of India which is home to kaḷarippayaṟṟ˘, as a teenager winning various state competitions before transitioning to dance. I brewed my strange-tasting tea and got better (I had less success with the ghee).

In 2010, I was able to rekindle my flame for kaḷarippayaṟṟ˘ by going to Trivandrum to train at CVN Kalari, by which time G. Sathyanarayanan Nair had inherited the role of gurukkaḷ. Gurukkaḷ is the Malayalam plural for the Sanskrit word for teacher, guru. This plural is a general honorific in Kerala culture, while also conjuring up the image of a gurukkaḷ standing with all the tradition’s teachers behind him, both supporting him and reminding him of his obligations as the lineage-holder. In kaḷarippayaṟṟ˘ these involve caretaking the martial art and ensuring its medical practice endures in a manner that serves its community, as well as fulfilling various ritual functions.

In the years that followed, I spent several extended periods at the kaḷari (the temple-building in which we practise, and which also houses the kaḷari clinic). I was puzzled that the little I could find to read about kaḷarippayaṟṟ˘ seemed to be describing something quite other than what I was experiencing. The gurukkaḷ had similar concerns, albeit from a different perspective, and in 2012 he suggested we start a documentation project together to fill this lacuna between written discourse and lived practice. Our initial discussions evolved into an exchange which is at the heart of my PhD in the Open University’s Religious Studies department, where I’m looking at how the embodied practice at CVN Kalari relates to its manuscript tradition. In particular, I’m hoping to see if I can find a way of writing about kaḷarippayaṟṟ˘ that is useful to people reading it who know nothing of the tradition, while also remaining recognisable to the experience of practitioners.

In May, I was supposed to present on kaḷarippayaṟṟ˘’s medical tradition at the closing conference of the AyurYog Project (http://ayuryog.org/) a five-year European Research Council funded project based at the University of Vienna that my supervisor, Suzanne Newcombe, was part of. Here’s my contribution to the online series the AyurYog project released in its COVID-cancelled stead.

In the hope that travel restrictions ease, I’m looking forward to spending time at the EFEO (Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient) in Pondicherry getting to grips with some kaḷarippayaṟṟ˘ manuscripts at some point in the second year of my doctoral research, before continuing my fieldwork at the kaḷari in Kerala.

Lucy May Constantini is in the first year of her PhD in the Religious Studies department of the Open University. Her doctoral research is funded by the AHRC Open-Oxford-Cambridge Doctoral Training Partnership. Two of her previous visits to the kaḷari were funded by the Arts Council of Wales and Wales Arts International.

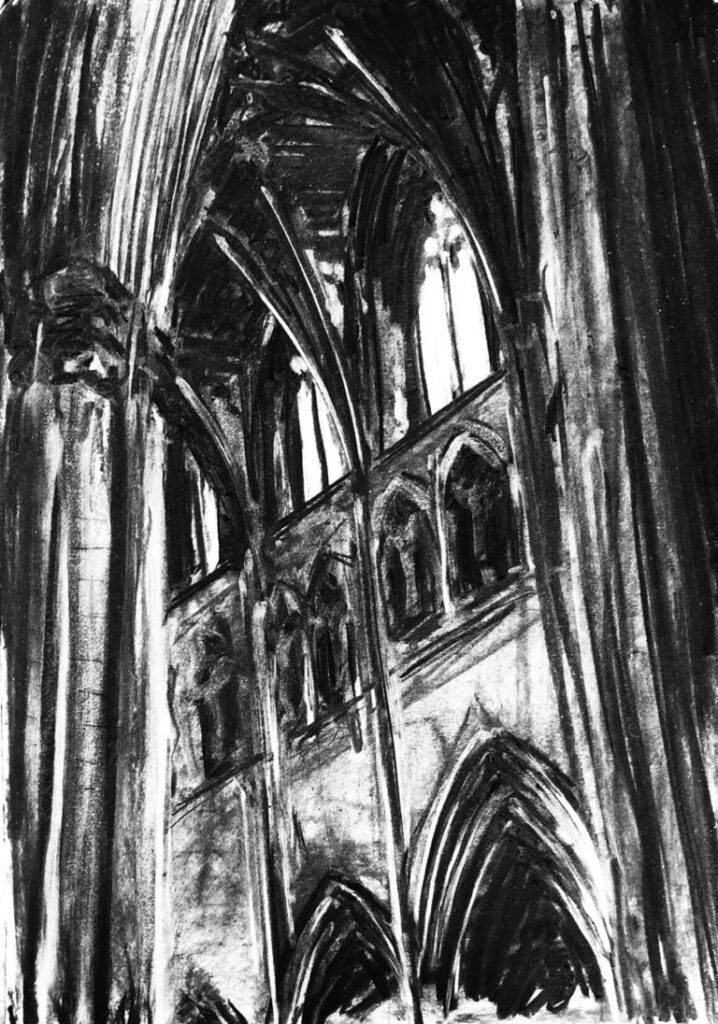

Photo: Sathyanarayanan Nair, Lucy May Constantini and the CVN Kalari community at the vidyārambham ceremony, 2016